PULSE VOL.2 (September 2022)

The polemic between Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana and Sanusi Pane in the 1930s over which cultural direction Indonesia should take - continuation of tradition or adoption of Western culture - led to a dualistic path in the cultural movement, including Indonesia’s new music scene. These conditions exacerbate differences that tend to be ‘negative’ and close the gate for the flow and development of culture that includes ‘dialogue’ between cultures. This phenomenon led me to the following questions: 1. What possibilities are there to break out of this dualistic perspective and how can I implement these possibilities in my music? In my piece Co[l]oto[mi] c[nal] I try to escape this dualistic perspective by engaging with both cultures, not by crossing the border, which can often end in simple appropriation, but by playing at the border, in the liminal space. In this liminal space, I have allowed my musical rhizome to grow in an increasingly more abstract direction, almost erasing a clearly audible ‘connection’ to the gamelan tradition because the line of development has already been broken and creates a new line of flight. This condition led me to another ‘space’ beyond the dichotomy, occupying the Third Space, the space that ‘shakes’ the fixed paradigm of cultural meanings and symbols.

Keywords: New Music, Gamelan, Spectralism, Liminality, Third Space.

‘Always follow the rhizome by rupture; lengthen, prolong, and relay the line of flight; make it vary, until you have produced the most abstract and tortuous of lines of n dimensions and broken directions.’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 11) [...] A rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines.’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 9)

INTRODUCTION

A few months ago I came across Deleuze and Guattari’s text on the phenomenon of rhizomes. In this text I found some ‘similarities’ between the authors’ explanation of rhizomes and my music , especially intrigued by their proposition to adopt multiple directions instead of a dualistic/linear process. The concept of multiplicity and non-dualistic orientation which characterizes the rhizomes remind me of some of my pieces, especially Co[l]oto[mi]c[nal]. This work for solo guitar provided a direct answer to my questions regarding how to find ways to escape the dualistic East-West perspective and how to implement these new approaches in my own music. This response is a direct reaction to the long history of the dualistic perspective between East and West that has existed in Indonesia since the polemic between Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana and Sanusi Pane in the 1930s.

In Co[l]oto[mi]c[nal], I ‘transformed’ the original function of the gamelan musical language to become something else with no linear connection to the original source. As Deleuze and Guattari wrote ‘the rhizome by rupture; lengthen, prolong, and relay the line of flight; make it vary, until you have produced the most abstract and tortuous of lines of n dimensions and broken directions (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 11).’ The musical materials in Co[l]oto[mi]c[nal] also behave like rhizomes, where the direction grows more abstract as the piece enfolds, losing an identifiable audible ‘connection’ to the original gamelan source by breaking the linear development paradigm to propose a new line of flight. The resulting structure no longer adopts the usual linear direction found in pelog and slendro to secure its ‘cultural identity’ and consciously avoids the use of simple banal quotations or reducing its unique intervals to the equal-tempered system to create something that Barbara Mittler called ‘Pentatonic Romanticism’. Here, I allow my rhizomes to evolve and ‘move away’ from their original form into liminal spaces (this term derives from the Latin word for ‘threshold’: limen), which can create ‘in-between’ conditions (e.g. timbre/frequency), and transform one musical language into another.

As a composer, I am no longer interested in ‘showing’ my roots or implementing my ‘cultural background’ in my musical composition. It is essentially impossible to remove the intrinsically ‘encoded’ cultural language from my music anyways. If you find any relation between my musical materials and my roots, it is because elements of those idioms are already ‘encoded’ within the fabric of my musical DNA. This phenomenon of ‘encoded’ cultural languages is explained from a psychological perspective by the Austrian music critic Max Graf’. Graf stated that impulses arise from the subconscious of a composer and go to the composer’s highest layer (consciousness). These impulses are formed from material deposits obtained based on experience, learning and thinking processes, education and culture as well as a composer’s knowledge of the world that settles in the lowest layer (subconscious). So, it is impossible to remove the ‘encoded’ cultural language from my music, but I can choose to play a never-ending ‘game’ with it, to find other possibilities, without being trapped in a ‘cultural identity’ topic that often ends up with a n inevitable dualistic perspective: here and there, east and west, us and others, etc.

Let us go back to Co[l]oto[mi]c[nal] as an example. As I wrote this piece, my rhizome was already being transformed, creating a multiplicity of directions and sometimes creating a ‘liminal space’ between two or more musical languages that I take over (and develop freely) from the previous ‘speaker’. For an individual like me who was born and raised in a multi-musical environment, the flexibility to choose multiple musical languages and pursue them freely is the ideal option as opposed to being tied to one of them, because I feel free to move when I do not care about how my music should be attached or connected to the tradition.

In the next section, I will further discuss the historical background and how this rhizomatic orientation in my music leads to the following conditions of liminality and third space. In the analysis section, I will show the reader how colotomic instruments function as a structural marker in Javanese gamelan music and how I consider its timbre and patterns as potential sources for constructing my harmonic structures (this non-linear ‘transformation’ itself already indicates the direction of my rhizomatic multiplicity, where one musical language transforms into another musical language in different forms, ways and functions). This practice inevitably creates a liminality between vertically structured frequencies and gamelan timbre, between instrumental patterns and chord progressions and so on.

The analysis section will then be followed by another section describing how I apply spectral methods to potential gamelan sources. This section explains how I transform colotomic instruments within my harmonic structures and how I utilise and modify spectral methods to achieve my ideas.

LIMINALITY, THIRD SPACE, AND HYPOLEPSIS

Liminal, Hypolepsis and Third Space are three terms I discovered separately which I find perfectly describe some essential aspects of my music. Before I go into the specific explanation of how these three terms are suitable to describe my musical ideas, I would like to give a brief history of the direction of Indonesia that were discussed by the founding fathers; this discourse relates to the musical options that stands on the threshold of both tendencies; standing in the liminal ‘space’.

In Indonesia, during the 1930s there was a polemic debate regarding which cultural direction Indonesia should take. The path should either divorce from the past - as stated by Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana in his essay ‘Menuju Masyarakat dan Kebudayaan Baru’ (‘Towards a New Culture and Society’) - or should be based on the local cultures - as stated by Sanusi Pane in his essay ‘Persatuan Indonesia’ (‘Indonesian Unity’); written in direct response to Alisjahbana.

Alisjahbana wrote, with great fervor, that the new cultural direction of Indonesia should be disconnected from the past because the past was no longer able to represent Indonesia within the new spirit of the time. This spirit could not be perceived in the past. He further added that this idea could also be realized by opening ‘the gate’ to accept and adopt some knowledge from the West observing the developments seen in Europe, America and even Japan. Pane criticized and opposed Alisjahbana’s thoughts and stated: ‘How can we disconnect ourselves from history, from the past?’ He further stated that ‘Indonesianness at that time (during pre-Indonesia history) already existed, Indonesianness in customs, in art’. (Pane, 1935) In his essay, Pane also explains that the West, with their geographical condition, was pushed to survive, that the use of intellectual thoughts and sciences a way to ‘conquer’ nature in order to survive in an extreme place. On the other hand, in the East, the geological condition is different, nature gives everything, and people do not have to conquer nature to survive, instead, people feel at one with their natural surroundings.

The resonance of this kind of polemic dualism still happens nowadays in Indonesia or even in the world: East and West, Us and Others, and so on. Why don’t we try other ways or directions? To achieve something out of the dualism tendency of East and West. This issue then led me to search how I can play a ‘game’ between the two; a ‘game’ that made my position no longer here or there, but stand in a liminal ‘space’.

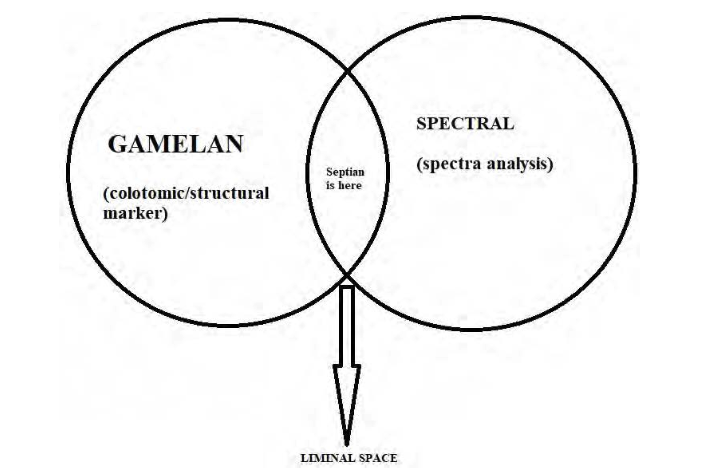

Figure 1: Septian is here

As I mentioned at the beginning of this article, my musical rhizome has inevitably brought me to a liminal condition which helps me to be able to ‘escape’ myself from dualistic thought. The idea of ‘liminality’ itself undergoes a kind of transition, [...] ‘it is closely bound up with experience and the processes of change, transformation, and transition that individuals undergo as part of that experience.’(Andrews and Roberts 2015, 136) Arnold van Gennep associates the term with a symbolic process that defines key moments of social transition, and Victor Turner argues that liminality (this term derives from the Latin word for ‘threshold’: limen) is ‘constituted in a condition or happenstance that has attributes of doubt and lack of inevitability between what is known and has gone before and future outcomes.’(Andrews and Roberts 2015, 132) Turner argues that people who are in the liminal realm ‘‘play’ with the elements of the familiar and defamiliarize (Andrews and Roberts 2015, 133),’ [...] ‘they are stripped of property or clothing which would mark their rank or status in the liminal phase making them indistinguishable from others who are sharing that experience.’ (Andrews and Roberts 2015, 133)

I am interested in adopting this liminal position, the position that has attributes of doubt and lack of inevitability between what is known and has gone before and future outcomes, the position that ‘play’ with the elements of the familiar and defamiliarize, the position that makes someone/object ‘indistinguishable’. Before entering the liminal space, I decided to take some of the languages from the first ‘speakers’. In the analysis section I will further demonstrate how I take the language of gamelan music and spectral music to achieve ‘free’ developments in my music. I termed this approach as ‘hypolepsis’. In the case of Co[l]oto[mi] c[nal], I continue to take the colotomic instruments’ functions from their cultural background and treat them through ‘spectral methods’. The two languages are then ‘distorted’ and placed into a liminal position between gamelan music and spectral music, occupying another ‘space’ beyond the dichotomy. This ‘Third Space’ is explained by the Indian theorist Homi K. Bhaba as a condition that can ‘shake up’ the fixity of cultural meanings and symbols (Bhabha 1994, 37).’ Bhabha goes on to say that ‘by exploring this Third Space, we may elude the politics of polarity and emerge as the others of ourselves (Bhabha 1994, 39).’ For me, this is a perfect way to escape the dualistic East-West perspective that has been prevalent in Indonesia for a long time, especially in the cultural movement, including music.

In addition to the unique ‘unrecognizable’ character of an ‘object’ located in a liminal ‘space’, this position is also fraught with ‘dangers’, for ‘the attendant risk attached to the entering of a liminal phase or liminal space is of losing a stable sense of self and identity.’ (Andrews and Roberts 2015, 133) However, I did not care about the dangerous side of the liminal space, because from the beginning my main goal was to lose a stable sense of cultural identity and to avoid the dualistic East-West perspective and rather to occupy another ‘space’ beyond this dichotomy.

In the next chapters I will explain and analyse in detail how those ideas were applied to my musical composition Co[l]oto[mi]c[nal]. I have divided the analysis into three sections where Iexplain how colotomic instruments function in Javanese gamelan, how the tendency towards spectralism was used and how both languages (Javanese gamelan and spectral music) were used to realise my idea.

COLOTOMIC

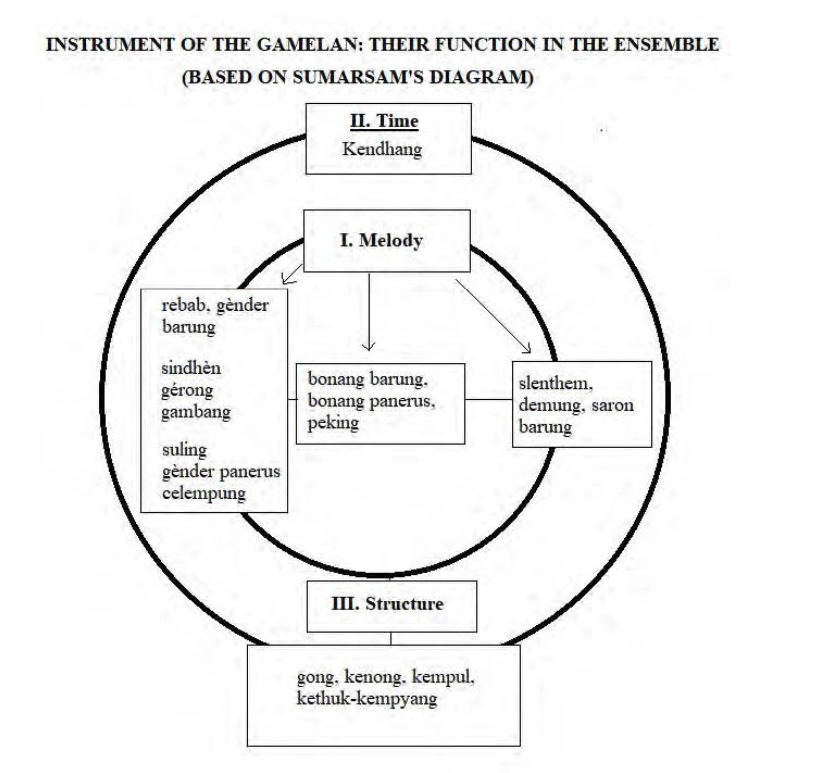

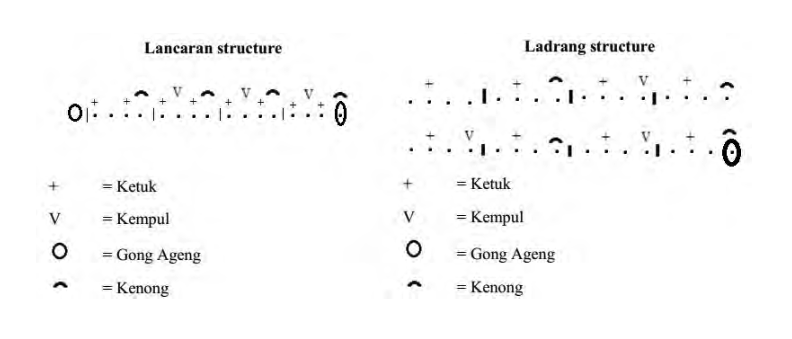

The Javanese scholar Sumarsam stated that ‘In spite of the complex process in which the musicians conceive and express their melodies, gamelan instruments can generally be classified according to their functions, into three major groupings.’(Sumarsam 1988, 6) The role of the first group of instruments is to play the melody; elaborate on the melody and generate melodic abstraction. These instruments are peking, saron, demung, slenthem, gender, suling, gambang, rebab, etc. The role of the second group of instruments is to become a structural marker; we can distinguish one style from another by listening to their pattern. I will give a brief example of this in the next part. These instruments are kenong, kethuk, kempyang, kempul, gong (usually people call them colotomic instruments). The third instrument, the kendhang leads the tempo through acceleration or slowing down of the pulse. The functions of instruments in the gamelan ensemble are very different compared to what is found in the Western musical traditions; I have not found, for example, that Fuga is distinguished from Rondo by the occurrence of instrumental patterns (e.g. Rondo style can be distinguished from other ‘Western’ music styles because the clarinet always appears on the second beat of every 2 bars in Rondo style). However, in the Javanese gamelan repertoire, we can distinguish two or more styles (e.g. between lancaran and ladrang) from their colotomic instruments pattern (see figure 4).

Figure 2: Instrument functions in gamelan

We can distinguish two or more styles in gamelan repertoire through the pattern of occurrence of the colotomic instruments (kenong, kethuk, kempul, kempyang, gong. See figure 3). In figure 4 (left side), the style is called lancaran, and on the right the style is called ladrang. These two styles differ in the pattern of occurrence of the colotomic instruments and I transform them by layering vertical frequencies extracted through a spectogram. By doing this, I transform the original function of those structural markers by turning them into harmonic materials; transforming one material to become something else which totally differs from the original context. The ‘source’ (colotomic) in my music no longer has a linear ‘connection’ to gamelan anymore, both in terms of function and shape, these elements now adopt a non-linear direction, growing as my musical rhizome illustrating the ideas of Deleuze and Guattari: ‘A rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines.’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 9)

Figure 3: Colotomic instruments signed by the red circles. Screenshoot from https://pad.philharmoniedeparis.fr/gamelan/index.html

Figure 4: Lancaran and Ladrang colotomic pattern. The black dots are the beats in a gatra (measure). There are 4 beats per garta. In Ladrang, for example, kethuk always appears on the second beat of each gatra.

SPECTRALISM

Spectral methods also become one of the techniques I use and adapt to achieve my musical idea; using colotomic instruments pattern as my harmonical source. However, as mentioned before, I did not take both elements (gamelan music and spectral techniques) directly from their original context; I take them from the first ‘speaker’ and develop them freely (hypolepsis). I use those possibilities only to create a multiplicity of directions (read: nonlinear); not continuing or keeping the historical lineage by, for example, forcing pelog and slendro to be adjusted to a completely different temperament or using a piano and call this new music based on the Javanese cultural background! Erqing Wang, one of my colleagues from China, calls this kind of ‘tendency’ as ‘Fake Asian Food’. He used this term when he gave his opinion of ‘Tabuh-Tabuhan’ by Collin McPhee while admiring the complexity of Dewa Alit’s ‘Genetic’.

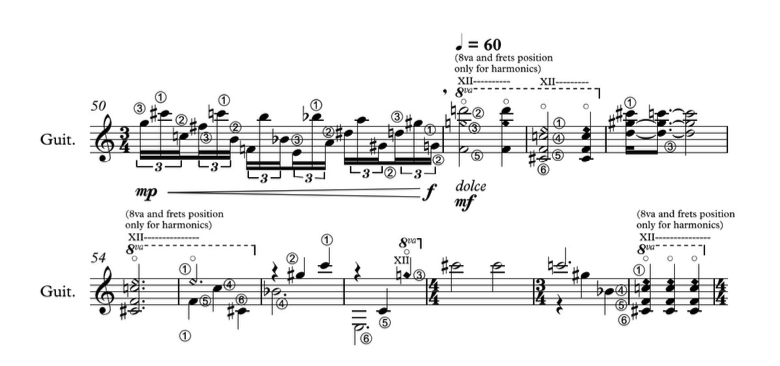

The spectral techniques in my music use only vertically structured frequencies extracted from spectral analysis of the timbre of colotomic instruments. I took some ‘opposite’ directions to the original method by exposing all the spectra of the colotomic instruments in the middle of the piece (see figure 5); not like in Grisey’s ‘Partiels’ where the spectra is exposed at the beginning. Perhaps this analogy helps understand the plot:

1. The ‘plot’ (the use of spectra) of this piece is like two styles of painting (abstract and realism).

2. In the beginning, I create an ‘abstract’ painting, in which all the colotomic spectra are distorted; not like Grisey’s techniques of harmonicity or inharmonicity, but allowing myself to add some frequencies outside the spectra of the colotomic instruments.

3. Towards the middle part the use of the spectra of the colotomic instrument becomes clear; you could imagine this part is like a ‘realist’ painting, where all spectra from the colotomic instruments appear in order; even the pattern following colotomic pattern in Ladrang Wilujeung (see Ladrang Wilujeung colotomic pattern in the next chapter).

4. After that part, I let the spectral constellation gradually blur again to return to the ‘abstract’ style. So the representation of the spectral constellation follows this path: A (abstract) → B (realism) → C (abstract).

Figure 5: Middle section of Co[l]oto[mi]c[nal]. The written notation and its sounding pitches are different because the guitar has to be retuned. Please see the full score to understand the sounding pitches (the link to audio and score is in the references).

FURTHER EXPLANATIONS

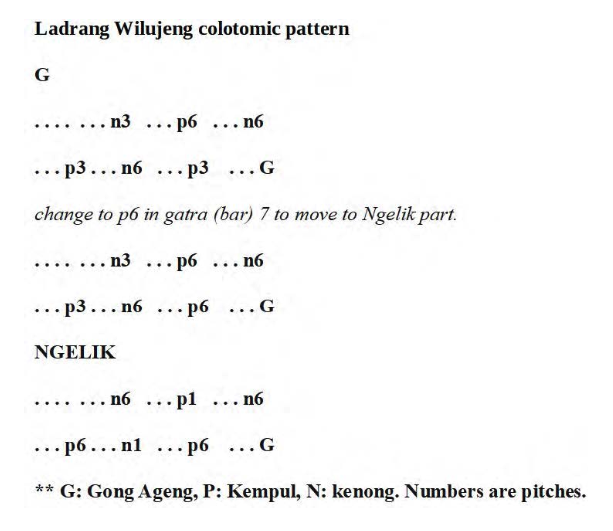

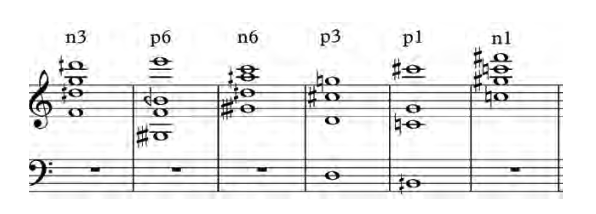

In this section, I explain in more detail how I transformed the colotomic instruments’ timbre to be used in Co[l]oto[mi]c[nal]. For this piece, I used Ladrang Wilujeng’s (a Javanese gamelan traditional repertoire) colotomic structure as the ‘source’ that will be transformed and used in my harmonic constellation. To grasps the pattern of ladrang style, you can see figure 4, and then move to Ladrang Wilujeung colotomic structure below (see figure 6); below I only write kenong, kempul, and gong pattern (but I also analyze the kethuk timbre), the number next to the alphabet is the pitches that should be played on kenong and kempul.

Figure 6: Ladrang Wilujeng colotomic instrument pattern

After deciding on the source, I started to analyze the colotomic instrument’s spectrum using a spectogram on my computer. From this analysis, I extracted a set of frequencies that I use in Co[l]oto[mi]c[nal]; I also use this kind of procedure in some of my other pieces such as s[TA]d II for Multiple Guitars, and s[TA]d III for Cembalo and Percussion.

However, since the guitarist was only able to use four-left hand fingers, I then decided to select only some of the frequencies (see figure 7); I implement almost all frequencies from this analysis in my duo piece ‘s[TA]d III’. In s[TA]d II, using a slightly different procedure, where I only analyze Gong Ageng timbre and use its result (fundamental and partials) as the fundamental to establish other partials from them.

Figure 7: Colotomic instruments spectra analysis result.

In this phase, the colotomic instruments that usually function as structural markers in gamelan already become something else (vertical pitches constellation); a liminal phenomenon happens, where the gamelan musical language meets spectral techniques to create a liminal compositional material that no longer belongs here or there ‘culturaly’. My rhizome has already grown in another direction, its line was broken, and creates new lines.

After establishing this main pitch constellation, I then move another step forward to add more harmonic elements out of colotomic instruments timbre analysis; I use them to ‘blur’ the main pitches constellation (this technique functions to fulfill the idea in points 2 - 4 in page number 9). In ‘Partiels’ by Grisey, the harmonicity and inharmonicities are caused by the multiples or not a whole-number multiple of fundamental. In my piece, the ‘inharmonicity’ is achieved by freely adding pitches based on the function that I desire; e.g. to create beating effects inspired by Balinese gamelan tradition. In Balinese gamelan for example, this kind of beating is called ombak; ombak (‘waves’) occur as a result [...] “of a paired unison tuned to the ‘same’ note-that is, identified as the same scale degree-but not tuned to the same frequency .’ (Vitale and Sethares 2021, 6)This technique then become one of the manifestations of the hypolepsis I mentioned earlier, where I take languages from the ‘first speakers’ and freely continue them; in this case, I have not taken gamelan and spectral music languages 100% in their original functions and context.

CONCLUSION

To be honest, I do not know how to conclude this article. It is not really an academic paper that starts with a problem or a research question and has to end with a result to answer the question. I have written this article only to explain my music in detail, to explain my tendency, especially how to escape from the dualistic perspective that has emerged since the polemic of Alisjahbana and Pane in the 1930s. In Co[l]oto[mi]c[nal] I try to break away from this dualistic East-West perspective by playing at the boundaries, within the liminal space, and occupying a space beyond the dichotomy, the Third Space, where I can break away from ‘polarity’ and ‘shake up’ the fixity of cultural meanings and symbols. Even though this liminality tendency might put me ‘danger’ of becoming an ‘unidentified person’ because I am deprived of the ‘property/clothing’ that would mark my rank or status in the liminal phase and make me ‘indistinguishable’, I carry on because I would rather do anything else rather than enter into the dualistic tendency between the ‘West’ and the ‘East.’ I argue that a stable sense of ‘cultural identity’ in music-making is not important. A music composition product should be fluid and not find itself jailed within the collective cultural identity of a community. Music composition is something personal, and the implementation of ‘cultural identity background’ to be noticed as from culture A, B, C, etc in music-making is not necessary. Musical composition is something personal, my music is me and does not represent me as a person who comes from Java. Just like Vladimir Mayakovsky’s poem, ‘I will speak about me and my time.’

REFERENCES

Andrews, Hazel and Les Roberts. 2015. “Liminality.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences.

Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. “The Commitment to Theory.” Essay. In The Location of Culture, 19–39. Routledge.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London: University of Minnesota Press.

Pane, S. 1935. ‘Persatuan Indonesia.’ In Suara Umum no. 276. (trans: Indonesian Unity).

Sethares, William, and Wayne Vitale. 2022. “Ombak and octave stretching in Balinese gamelan.” Journal of Mathematics and Music 16 (1): 1-17. doi: 10.1080/17459737.2020.1812128.

Sumarsam. 1988. “Introduction to Javanese Gamelan.” https://sumarsam.web. wesleyan.edu/Intro.gamelan.pdf

AUDIO + SCORE

https://opensea.io/assets/matic/0x2953399124f0cbb46d2cbacd8a89cf0599974963/ 77666440287095994676559531674335593228427583122760605038221848338138 017038337?fbclid=IwAR01nh9HXD4agFgpzKc064C8vJ8aZwdcPjbHTCKxcA9M 49Z-quHCRJAS7L0