PULSE VOL.5 NO.1 (August 2024-January 2025)

PLAY AND INTERPLAY: MODELLINGPARAMETERS OF INTERDISCIPLINARYCOLLABORATION OF MUSIC AND VISUAL ARTS

-Andrew Filmer, Yeoh Pei Ann, Maslisa Zainuddin, Mohd Firdaus

Abstract

This collaborative project brings together artistic expression of musical performance with painting, building both one-way and two-way connections between the art forms, with video recordings emerging not just as documentation, but creative products in its own right.

The project has had three iterations, or “episodes”, thus far; each expands the parameters of the collaboration. Music began as half preset with solo works of J.S. Bach and eventually became purely improvised interplay between two musicians. Videography began with the intent of recording the event and eventually became live projection and an active element in the performance. The first episode was under pandemic restrictions, the second included an audience, and the third was a three-day event comprising exhibition, workshop, and performance — and the expansion of the team to include a new musician and an assistant to the videographer.

Throughout this experimental engagement now in its third year, our mission was to explore interdisciplinary crossroads: how do people from different art forms collaborate? Does this collaboration bring out creativity or expressiveness or both that would not be the case with each art form in isolation? How does the performative element and the inclusion of audiences influence the painting or the music or the way these interact?

In some ways, we find more questions than answers, but even so there is value in knowing which new questions to explore. In other ways, we create a model of interdisciplinary engagements of this nature, to visualise some parameters within which artists, performers, and audiences find play and interplay: as the title of the project suggests, a Garden of Sight, Sound, and Surprise.

Keyword: cross-disciplinary collaboration, musical interplay, improvisation, music and visualisation.

Background and Approach

A project that provided foundational influence on this project was that of Ayse Guler and Valerie Ross, as presented at the Centre for Intercultural Musicology at Churchill College, University of Cambridge in 2019, and published in 2021. [1] This project involved the production of some 63 watercolour paintings by Guler inspired by Symbolic Gestures, an electroacoustic piece by Ross.

Both projects shared some similar aims and conclusions, particularly in discovering the nature of creativity in artistic intersections. [2] Where our projects differ is the way in which we approach the development of intuition and creativity. Guler looked into the translation of music, while the present project also looks to some two-way connection between both art forms. Additionally, Guler’s approach involved a stage of “listening to the composition repetitively with full concentration”, noting that “repetitive listening then is essential to allow the painter to hear the composer’s musical insights.” [3] The present project relied on synchronous, real-time musical performance and painting, a pre-requisite of the two-way project and live exhibition, with the ‘limited resource’ of aural content – put plainly as “not being able to rewind” when asked by the audience – being a component of the experience, and the experiment.

Miguel Jerónimo’s AffectiveWall project has a peripheral impact on the present study. [4] Similar to Guler and Ross, it seeks to have a reliable translation of music and painting – though in this case, both art forms are translations of gestures. It is helpful insofar as understanding how music performed in settings other than in recordings encompass more than sound – where body language plays a role, whether consciously or unconsciously.

Informative to a wider understanding of the connection of music and visual arts is “Visual Music” by Maura McDonnell and the Transformative Reflections project of Nikolaj Hess. McDonnell provides an expansive exploration of the history of connecting music to visual arts and media, dating back to the first half of the last century. Experiments often looked for logical correlations between sound and sight, with references as far back as Isaac Newton’s theories of colour and pitches. Dissonance in atonal music was, early on, “comparable to the freedom and creative energy in abstract painting” by the likes of Wassily Kandinsky, and the advent of film allowed for the concepts of motion in music to be mirrored by movement in the visual arts. The presence of “non-representational graphics” was deemed crucial to connecting to the feelings of observers, and practitioners went as far as to create instruments like Alexander Rimington’s “colour organ” to bring visual arts into the performative, “composing” domain.

Hess explores “visual art as a spatial concrete expression, and the possible translations to compositional and improvisational music, as an ephemeral temporal expression.” The process is described as alternating between “translation, reflection, interpretation, and transformative reflection”. This project brings out concepts we deal with in our own: intuition, inspiration and dialogue, with some others that were not: the idea of the concrete and aspects of analytical thinking.

The Episodes

Episode1 was held in early 2022 when public performances were still restricted due to the pandemic — the artist and musician began the exploration of two converging art forms, with the videographer to document the event. Half of the music was pre-set (unaccompanied works of J.S. Bach, chosen by the artist), and the other half was improvised.

Figure 1 Episode 1 unaccompanied works of J.S. Bach with musician away from the canvas

Figure 2 Episode 1 Solo improvisation (musician having just left the platform). Live Arts Space,Sunway University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, February 2022

Illustration 1a. Episode 1. Left: unaccompanied works of J.S. Bach with musician away from the canvas. Right: solo improvisation (musician having just left the platform). Live Arts Space, Sunway University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, February 2022.

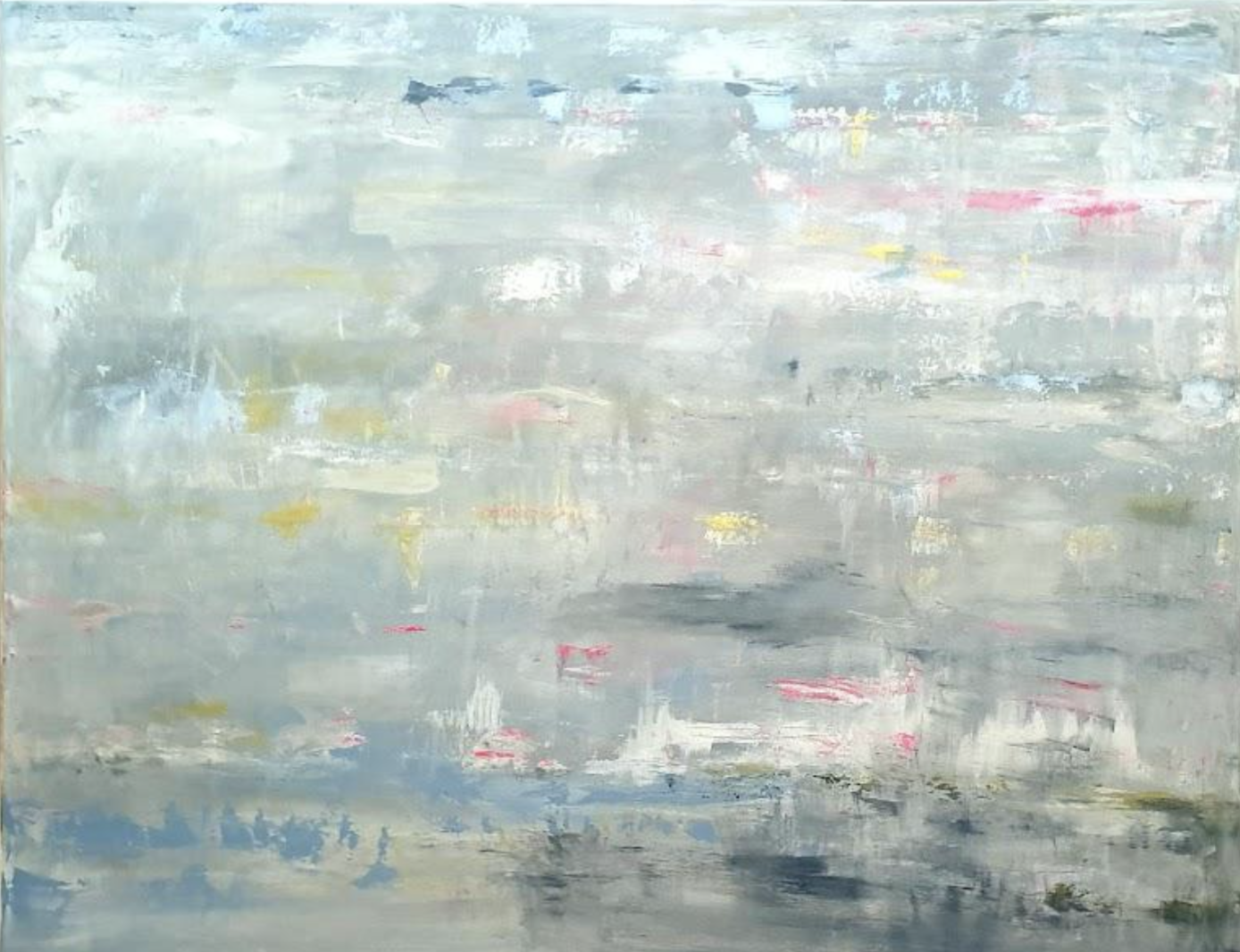

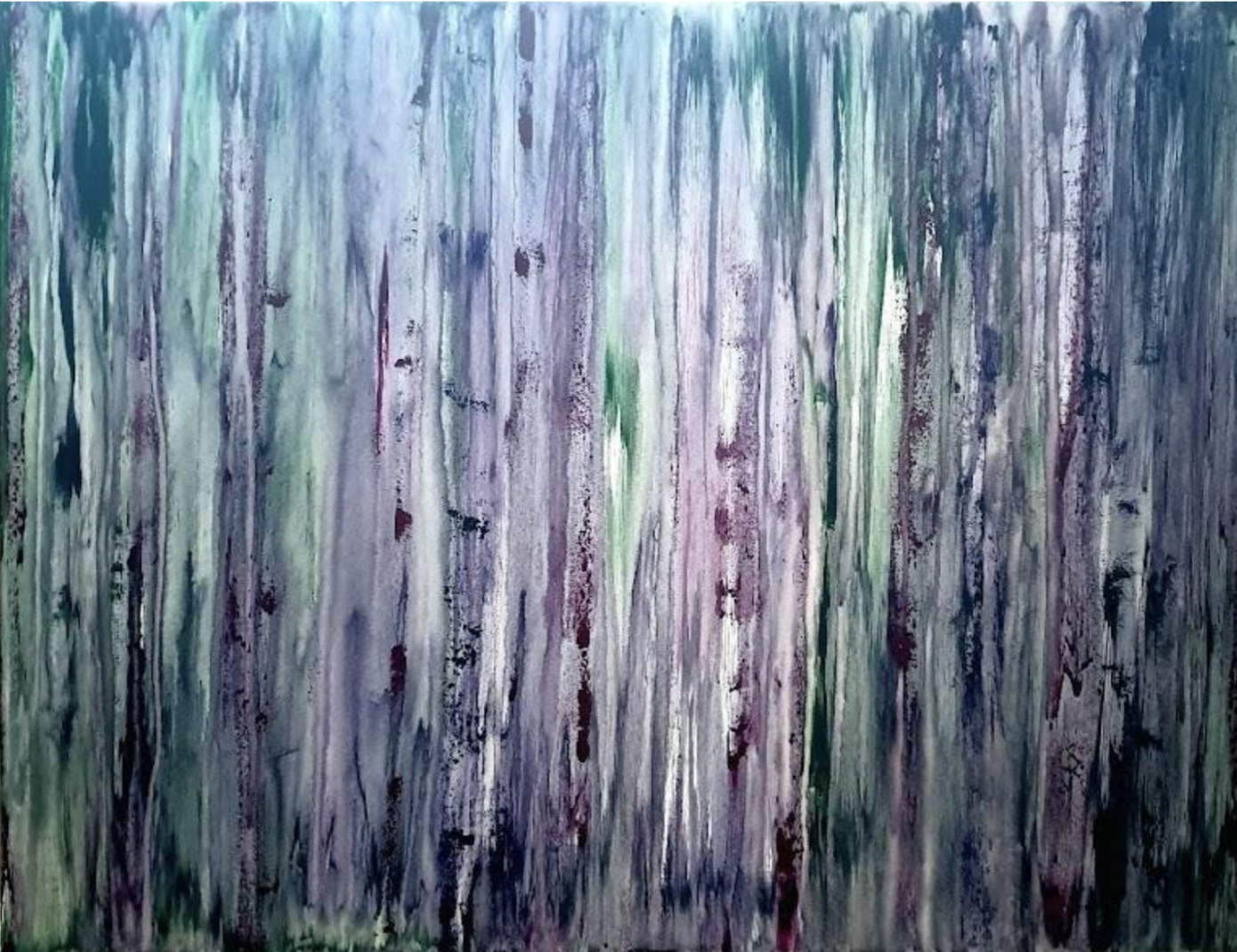

Figure 3: Episode 1 Scorresponding paintings

The video outcome of the Garden of Sight, Sound and Surprise, Episode 1 is available here:

Figure 6 U Yi Nwe Tribute Concert: Nay Win Htun, Ne Myo Aung with Dr. U Yi Nwe in January, 2020Figure 7 At Inya Lake Hotel with bass player Ko Myo In 2006, Goesta established a Baroque orchestra for which he returned twice a year as a volunteer to conduct and also teach Jazz

Episode 2, held a few months later, brought in a public audience. This event provided an exhibition of the outcomes of the previous collaboration: not only the two paintings, but also a projected video. It was over this backdrop that the second experiment took place, using the same personnel with the added influences of audience and exhibition. Half the event was the music and painting, while the other half was an intellectual discussion with members of the audience, largely from the university community.

Figure 4: Episode 2 Painter’s point of view with musician and projection mapping inview. School of Arts Gallery, Sunway University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, May 2022.

The video outcome of the Garden of Sight, Sound and Surprise, Episode 2 is available here:

Figure 5: Episode 2 Three resulting paintings

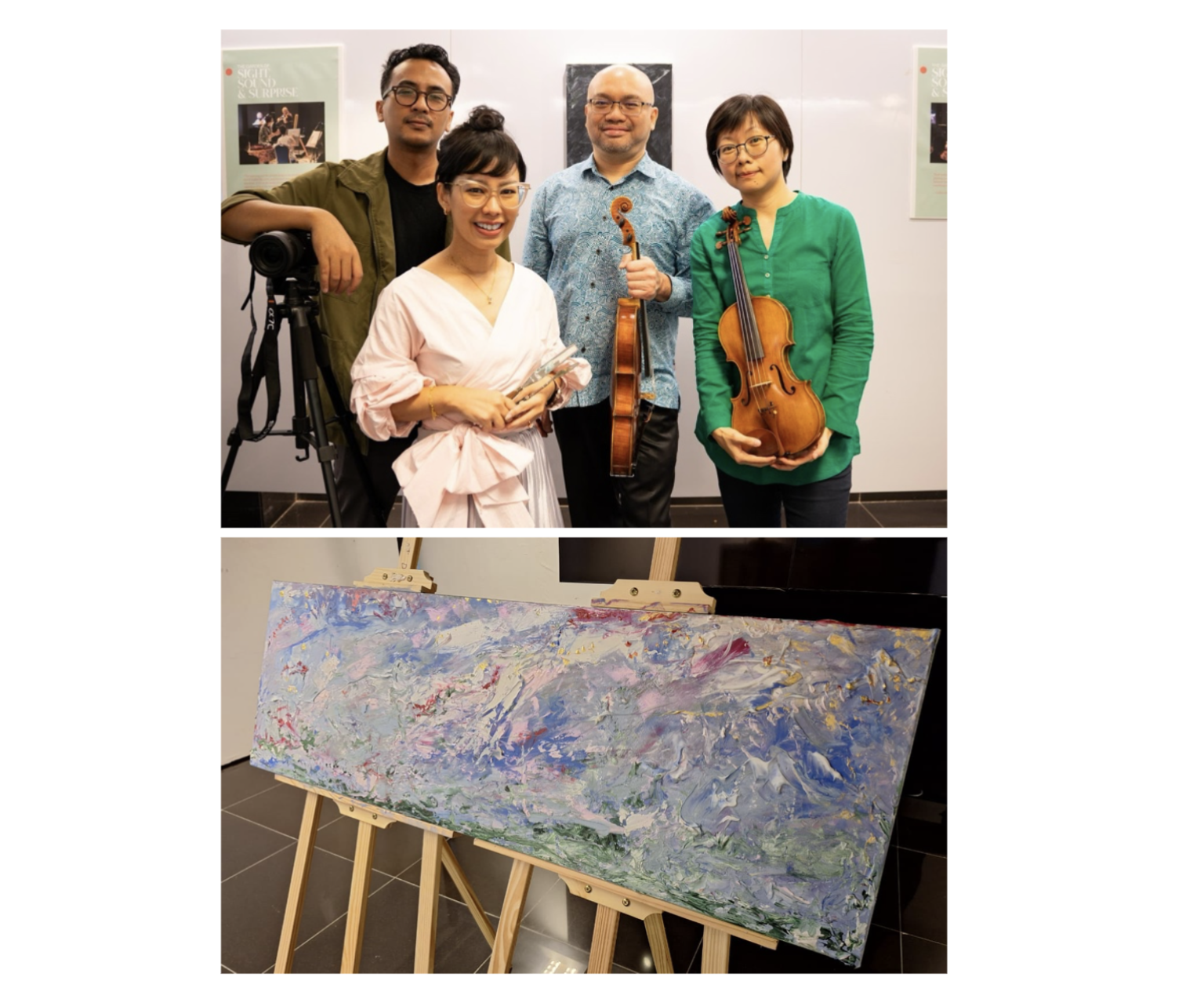

Episode 3 took place in late 2024, expanding the team to include a second musician, and with the event spanning three days covering exhibition, workshop, and finally the performance. Interaction with the audience varied in that some conversations began at the launch of the exhibition and concluded two days later after the music and painting had concluded. In addition to the inclusion of musical partnership, the technology was expanded as well to include live projection of the event.

Figure 6: Episode 3 The expanded team of Episode 3, and the resulting painting. UiTM Univer-sity,Selangor, Malaysia, October 2024

The video outcome of the Garden of Sight, Sound and Surprise, Episode 3 is available here:

Figure 7: Close-up excerpts of the painting.

Evolutions of Interplay

Episode 1’s original experimental collaboration — or, perhaps, collaborative experiment — explored the crossroads of music and visual arts. In doing so it explored several facets of this artistic endeavour:

•Painting in reaction to pre-set music, contrasted to painting vis-a-vis improvised music

•Videography intended as an inert element of image capture

•Pre-conceived ideas of how music would be conceptualised on a canvas There were surprises at this stage, with classical music emerging not in the dark hues one might think of music of a bygone era, with the artist reflecting, “The painting ended up looking like a lively little garden scene on a cool summer’s day – it felt like it had energy.” This led to the title of the project, both in imagery of the garden and the central figure of surprise.

The videographer’s role was meant to be behind the scenes, but the absence of an audience made his movements an influence on the improvisation. The musician noted: “There are some times when he walked quite fast to build the panned shots. If it matches what I’m playing at the time, I build it into the playing.” Additionally, “In the improvisational parts as well... he’s the active ingredient in the room: even when he’s behind you, you can see his shadow. It was quite interesting to work with that.”

A key area was how there was pressure to build synchrony of bow strokes and brush strokes — overtly intentional rather than two random artistic events happening in tandem and with no relation to each other. This created a sense of unease with the artist, resulting in one-way brush strokes and darker hues. This facet would be explored further in the following episodes. In Episode 2, there were a new elements for exploration:

•The inclusion of an audience and its effects on the artist, musician, and videographer

•The choice to limit direct synchrony to produce a more organic effect

•The expansion of the event to include a small exhibition and extensive public conversation

The prominence of the performative element literally took centre stage here. The artist, who felt that she was “stalked” in Episode 1’s contrived synchrony no longer had this element — but this seemed to be transferred to the audience. At the post-performance conversation, dean and musician Matthew Marshall commented:

“It almost felt uncomfortable to me in that I’m observing something that I normally wouldn’t or would be excluded from. Almost like I was a voyeur watching you paint; I felt like I had to keep looking away. How did you feel about having the audience here – did it make a difference?”

The painter responded: “Honestly, I forgot that you were here.”

The musician added that it was strange to have the attention of the audience on something else in the room. “I’m used to having an audience, but I’m not used to the audience not paying attention to me. Then I felt really independent – it doesn’t matter what I do.” The initial reaction seemed to parallel the well-known experiment of famed violinist Joshua Bell busking in a subway.

The videographer’s role as the editor later in the process helped him to further develop the flow of the Episode 2. In terms of camera movement and planning, the videographer was no longer shackled with the assumption to produce something that was deemed “elegant”. This realization resulted in experimentation with a Dutch canted angle to evoke a sense of unease for the viewer.

If there was a jump from Episode 1 to 2, then there was a leap to 3: the expansion of the project to include another musician from a different university, and an extension of the event to three days, covering exhibition, workshop, and performance — not to mention the two-year gap in between. In Episode 3, new horizons included:

•The effect of musical conversation with two improvisers, and no pre-set music

•The development of the performative element, with the videographer’s live projection

•The audience as influence not just in post-performance reflection, but in preceding conversations

A stark contrast was seen in the videographer’s role — while in Episode 1, he reflected that “I was self-aware that I shouldn’t be too near to either of you because I think that would tamper with your process in a way.” In Episode 3, he bumped into the musician while in performance, and was not surprised that this happened. “I know we are going to touch and something will happen. I know I’m extremely close to you because I want to get your shoulder shot and I think the movement of the bow is very interesting and I know at some point I’m going to be touching.”

The three-day span, with the exhibition of five completed paintings, allowed for reflections of the project as a whole through conversations with visitors, as well as small trials both of musical improvisation and painting, and conversations on approaches and interpretations. A wider discussion emerged on how to define the project (as event versus process, or performance versus production, creativity versus expressivity) and how we dealt with the urge to find that which was different without simply resorting to complexity.

The improvisatory process was brought to greater focus not just through the absence of pre-composed music. The videographer reflected that his role became improvisatory as he weaved through the new performance space: “Improvising through these spontaneous moments felt much like folding a fitted sheet—an initially chaotic process that, once you find the right edges, folds into something beautifully aligned.”

The artist, now with performative experience and in the transformation of the traditional isolated experience of painting, reflected: “Knowing that the process was being documented and projected live, created an awareness of both the art being made and the story of its creation. It felt like a ‘performance of process’—a shared experience.”

II. Discussion: In Between Phases

This section considers the challenges of interdisciplinary work which transforms artistic conventions into meaningful collaborations. It interrogates the nature of interdisciplinary collaboration through a developing understanding of ensemble roles. Part of the challenge may lie in the articulation of artistic form and method. That is, how we articulate our creative roles influence the interdisciplinary practice and subsequently, the research value of interdisciplinary work. In this way, we establish how artistic research emerges from our creative practice. We also consider how artistic research functions as our theoretical framework and also as a metaphor for interdisciplinary encounters. As the third iteration of the project, some changes were implemented, not least the addition of one more musician, the change of location, and the extended period of production over three days which allowed all members to recall, reflect, and reimagine their roles within the creative process.

The use of improvisation as the main tool of expression had its basis in drawing out creative interactions to engender new artistic responses. Initially, it generated some anxiety for the practitioners – especially in the first two episodes where there were many unknown outcomes. What was improvisation for artists who generally rely on external influences to inspire their pieces? What about videography whose role was primarily ‘to document’ the event? How can a videographer influence the liveness of the improvisation? Should it? Improvisation may be clearer for a musician, but there was also a desire to relate or ‘to make reference’ to the artwork which could potentially inhibit the improvisatory spirit. The multiplicity of our roles (as musicians, painter, and videographer) was challenged in the process of creating the work.

Along with our anxieties about using improvisation as our creative approach, our primary concern was to establish a creative outcome. But in an interdisciplinary encounter, this became a fundamental problem. Was it a single work that was produced? Yet, if there were multiple works being created, how is the artistic work heard, shared, and validated – particularly in a scholarly context? How do we perceive our artistic roles when we use music, art, and media to collaboratively develop a creative work? Quite simply, what are our creative positions in an interdisciplinary context? Inadvertently, developing an understanding of interdisciplinary collaboration became our research purpose. While the project was not designed with an intention for research inquiry, issues in interdisciplinary work emerged from within our practice.

Here, we considered artistic research as our model for interrogating interdisciplinary work. In the context of how our project developed into a research inquiry, it can be thought of as ‘practice-led research’. As often the case with artistic research, issues or problems emerges from the creative practice, with the creative process seen as a way to examine the research questions. In a fit of irony, the creative practice both reveals our research objective and is the methodological tool from which we attempt to derive new knowledge. This juncture is sometimes seen as ‘practice-based research’. However, going even further into the paradigm of artistic research, the creative work is then both the research process and the research outcome. This might even be considered ‘practice-as-research’. Problematic as these positions may present, the nuance of artistic research stems from the diversity of creative practice and contextual richness of the material. Mapping this onto our interdisciplinary project, artistic research as a framework offers a theoretical approach to articulate the project as a research inquiry and a practical frame to interdisciplinary practice. After all, artistic research outlines an interdisciplinary relationship between artistic practice and scholarly work. It becomes both the framework and metaphor we adopt for our project.

Henk Borgdorff suggests that if artistic practice is contingent on research, it is possible to perceive the converse: artistic research as contingent on artistic practice (2012). In part it is to manage the parallelisms between creating artistic work and conducting academic research. Where the articulation of research question generally assumes primacy in shaping the outcome of research; in artistic research, it is the creative practice which initiates the field of interest and ‘not only precipitates the research process but informs it and is shaped within it’ (Burke & Onsman, 2017:10). In other words, articulating one’s artistic practice is as essential in developing it, as it is crucial in defining the scope and method of research. This kind of ‘discipline formation’ through language which was outlined by Darla Crispin may lead to other anxieties regarding artistic research, framed as ‘me-search’ rather than new insights (2019). Thus, the balance of subjectivities, that is, the way we identify and represent our artistic roles, returns us to our initial position when establishing our interdisciplinary project.

One of the first points of reflection was identifying what ‘The Garden of Sound, Sight, and Surprise, Episode 3’ was. Was it a performance or a production? The space was set up with the intention of creating a performance space where the musicians will take to stage, facing rows of chairs. Yet, there were several cameras for wide static frames and close-ups akin to a production setup. In the middle of it all was an art studio, a blank canvas set up with a volume of paints and brushes. The labels may not be important to us as practitioners, but interdisciplinary collaboration demands clarity of perspectives so that creative value can be assigned in recognition of how interdisciplinary impact has taken place. Similar demands are made of artistic research too as it establishes research value to the project. As practitioners, it is our reflexive interaction which develops the creative process. As researchers, the reflections represent critical research data of the creative process.

Each discipline – the music, art, and media can stand independent of each other, separate from the performance or production, with its own creative value that is particular to the nature of the artistic practice. However, the artwork, music, or videography in and of itself cannot represent interdisciplinary work. What draws it together in interdisciplinary form is actually the writing, the textual expression of that interdisciplinary process. In other words, it may be an interdisciplinary practice as far as we can observe it, but it is not interdisciplinary work until we write about it. But what are we really writing about when we write about interdisciplinary work? Parallel to that, what are we writing about when we write about artistic research? As artistic researchers, these phases between knowledge and practice are essential to deepening our perspective between creative practice and research work.

Robin Nelson suggests that one way to dissolve the binary between theory and practice is to mobilize an interplay between conceptual thinking through critical reflection and practical doing-thinking (2013:29). In other words, a heuristic analysis is necessary to deliver critical research data – partnering both the artist’s reflection with a reflexive interaction with the research material to continually formulate and develop the artistic work. Artistic research becomes a recurring cycle between research practice and creative practice, with the practitioner-researcher modulating between reflective and reflexive approaches throughout the project. This was precisely the interplay which we modelled in our interdisciplinary interactions with each other – at once reflecting the artistic moment and reflexively engaging with each other.

Interplay: Aural, Textual, Visual

This manner of interplay is applied in our approach to interdisciplinary practice. Reflecting on our project, we discovered the interconnectivity between each discipline through the perspectives of each other, blurring the initial roles we had established for the project. Our perspectives were opened to other possibilities of looking at artwork as musical score or listening to music as a visual spectacle. The interplay between art and music lends itself to a creative relationship that is relatively common in interdisciplinary practice. This correlation between art and music can also be found in a cognitive condition known as synaesthesia where an inter-sensory experience with taste, sight, sound can be activated simultaneously. The earlier episodes (Vol.1 and Vol.2) explored this relationship between sight and sound in an almost linear direction. It was when videography entered this space, the project engaged with a new dimension of interdisciplinary practice. We consider this to be the ‘surprise’ element, enhancing what we had first established as the primary creative source in art and music. The post-production aspect fed into our creative consciousness which we reflexively engaged with.

The initial motivation of having videography was for documentation purposes. However, post-production outcomes revealed new particularities of the creative process that had taken place between art and music which required further reflections in developing the next project. In other words, new creative perspectives that were being presented from the singularity of video capture and edit shaped how the next project was structured – from Episode 1 to Episode 3. As a reflexive interaction, recognizing the influence of post-production output through videography allowed new interdisciplinary settings to take shape, creating space for interdisciplinary encounters to emerge from within. The growing influence of videography in this process is testament to an interdisciplinary practice that is inclusive, provocative, and generative. In Episode 3, the reflections from our videographer included terms such as ‘rhythm’ and ‘composition’ – quintessentially musical ideas, common also to art and videography, but here, our interdisciplinary perspectives were expanded to enrich the intertextuality of our artistic practice.

In the performance-production of ‘The Garden of Sound, Sight, and Surprise, Episode 3’, the reflections brought out other underlying perspectives of the experience shifting between expressing (music), translating (art), and representing (video). How interchangeable were the three positions in the moment of creative work – and crucially, have we begun to be influenced by each other beyond our disciplines? That is, might we now be performing for the piece/artwork/creative output? This intertextuality began to emerge in our reflections. The music, which was our expressive element initially, gradually engaged with translation and representation of the process. One musician moved around the canvas midway of the performance to observe the painter – changing the dynamics of engagement from one who was expressing to one who is representing and translating the visual elements. Conversely, the artwork which began as a form of musical translation also had expressive elements to offer the other practitioners. Each stroke of the brush was being projected live, akin to a performance which the musicians could observe. Our videographer may be representing the entirety of the project in a post-production clip, but he also expresses and translates the performance he captures as he moves in and around the space – influencing the live elements.

While we retained our original roles as musician, painter, and videographer in practice, we have transcended our perspectives to conceive of the creative work as a collective. The painter’s reflection echoes this through the lack of fear she felt and the trust that was built throughout the 3-day exhibition. Aside from thinking of the artwork as a form of translation of the music she heard, there was an expressive aesthetic that was singular to the painter. The artwork was also representative of the improvisation and the improvised settings that were in place. The same can be said about the musicians. Aside from improvising to an internal expression, they were simultaneously translating and representing the context of the performance-production through music.

This suggests that interdisciplinary practice, when nurtured, can develop into an interplay of all the elements together. The connotation of ‘play’ as opposed to ‘discipline’ is pertinent here as it exemplifies the intuitive nature of creative work as opposed to the intentional practice of artistic craft. Where ‘discipline’ might be considered a more rigid practice, ‘play’ transcends that discipline and allows creative practice to flourish. The idea of ‘play’ was also evident in our videographer’s reflections of finding ‘rhythm’ from his response to framing the artists and their movements. There was greater overlap between performance and production spaces that was bridged by videography, sharing in the creative roles and enriching the interdisciplinary experience. This simultaneous process between expressing, translating, and representing through the different disciplines offers us a framework for understanding the various experiences that can occur during collaborative experimentation. It is representative of artistic research framework which utilizes both reflective and reflexive positions to develop simultaneously the creative and research work.

Sustainability of The Creative Process

There is a general reliance on disciplines to establish boundaries on which to prop our excellence. This is both a necessity and a liability. There are great benefits to perpetual engagement within the discipline to elevate the craft from an artistic account. However, it runs the risk of isolating the creative practice and descending into farcical imitation within the discipline. Furthermore, the subjectivity of artistic quality means that some limitations will naturally inhibit (or even, prohibit) the practitioner from further exploration within the discipline. Interdisciplinary practice, however, invites us to consider new ways of producing creative work outside the confines of the discipline.

Beyond the conventions of artistic practice, interdisciplinary collaboration calls on us to radically alter our mode of expression, production, and performance. It enlarges our perspective from a singular form into a multi-layered texture, challenging us to view authorship from a collective standpoint. While the musician may not have wielded the brush that painted the strokes, the music was nevertheless an essential part in the creation of the artwork. Similarly, while the videographer may have played no part in laying bow to string, the act of capturing a live session indirectly assigned musical and artistic values to what was displayed. This shows the interaction between ‘discipline’ of each member against the ‘play’ of the creative process as a complementary whole.

Crucially, interdisciplinary collaboration requires greater textual articulation for a broader engagement within its neighbouring practices. While the strength of the creative work lies in the artistic capabilities of its practitioners, the value of interdisciplinary work lies in the creative relationships built over a few episodes. The singularity of artistic work is iterative of itself and runs the risk of repetition. Interdisciplinary work, on the other hand, is generative in spite of the repetition that occurs because of a creative interaction that is beyond artistic material. This, and other intangibles offer an opportunity for artists to consider new and sustainable ways of expressing, engaging, and encountering the world.

III. Modelling (Inter)Play: Framing Collaboration

In reflecting on our collective endeavour, we attempt in this section to visualise some of the axes or parameters that helped create artistic meaning within our multi-faceted collaborations.

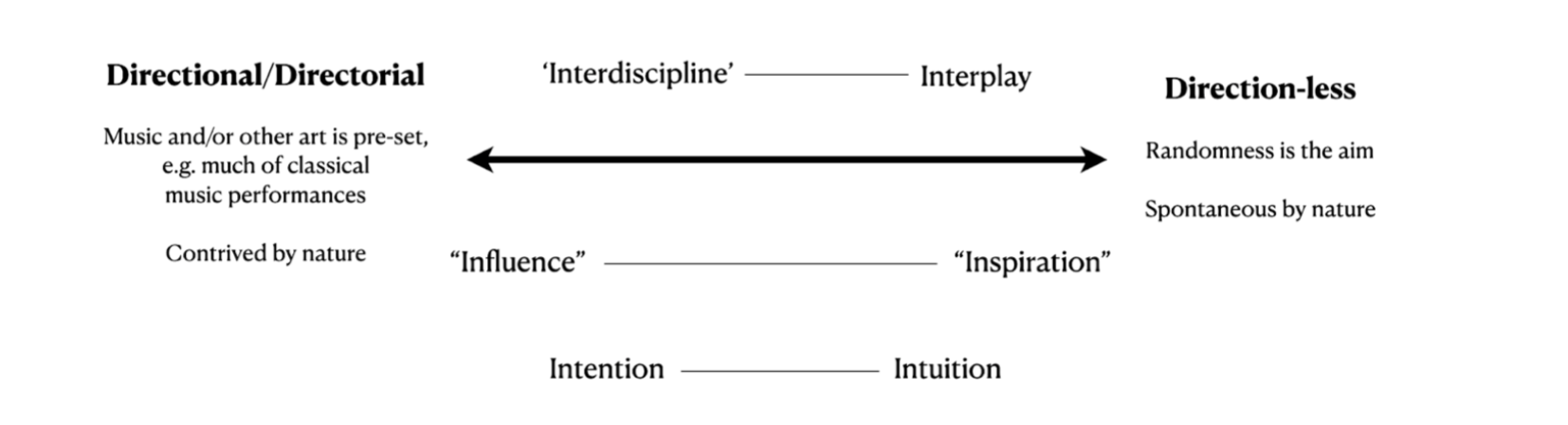

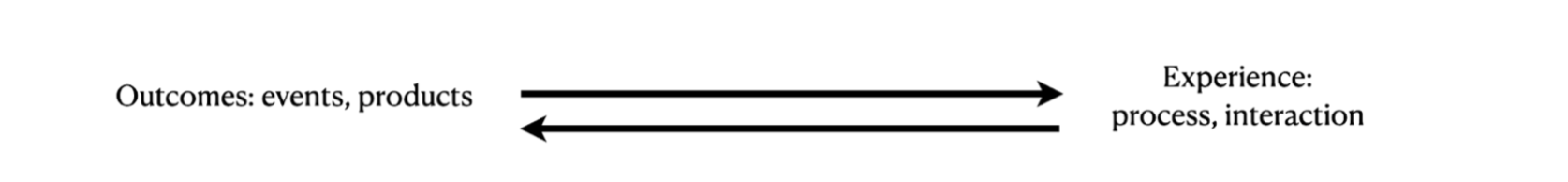

The first, perhaps most fundamental of interplay principles is the question of direction, as seen in this first diagram:

Figure 8: Visualising direction in improvisatory collaborations

On the far left we have familiar territory of pre-determining the course of interaction — this is certainly common in music: playing precisely to sheet music at the baton of a conductor (in some languages, literally “director”), composers putting in specific instructions, including precise metronome markings, recordings following a click track. On the far right we have some aleatoric music or perhaps pure soundscapes: birdsong being presumably oblivious to flowing streams and rustling leaves. These parameters provide certainty on one end, where being contrived is an asset or even a necessity, and spontaneity on the other, where capriciousness is a virtue.

We find ourselves in the middle. Interplay reminds us that there is indeed the spontaneity of play; meanwhile, interdisciplinary efforts suggest to us that there is discipline. Even in improvisation there is a sense of intention, especially in responding to another person: do I play to the camera? Do I imitate a brushstroke? When responding quickly to impulses of others within a performative setting, the premeditated nature of intention can give way to intuition — the common parlance of being “in the moment”. The final two “in”s were proposed by a member of the audience, Danial Nawfal, who wrote: “Influence here, in this space, did seem to carry the implication of something more directive in force, a subtle shaping of the painter’s response based on specific melodies and movements.” This in turn “established a sense of reassurance, a cohesiveness in which both artists seemed to be voicing a common message.” Contrastingly, “inspiration in collaborative settings differs from influence in that it allows a less prescriptive, more open-ended prompt for creativity. Where influence might have elicited in a particular direction the response of the painter, the musician’s gestures and facial expressions sparked interpretations that allowed him to bring in unique layers into the work. These visual cues reduced uncertainty and created an atmosphere in which each artist could trust his message was both shared and understood.”

Within the larger arena of determining the very nature of the collaboration, we felt that there were certainly tangible outcomes (recordings, videos, exhibitions, paintings), as well as what could be generally seen as “experiences” — not just the interactions or the process in which we were engaged in one particular moment, but the effect of a three-day production, or, more broadly, the three-year engagement.

Figure 9: Interlinked nature of outcomes and experiences

Putting this all together provides us a framework for understanding the various experiences that are “in play” with our collaborative experimentation. One important factor to note, particularly in the first of our diagrams, is that we can dance along the spectrum of direction and spontaneity, and that a performance as a whole can include elements of both.

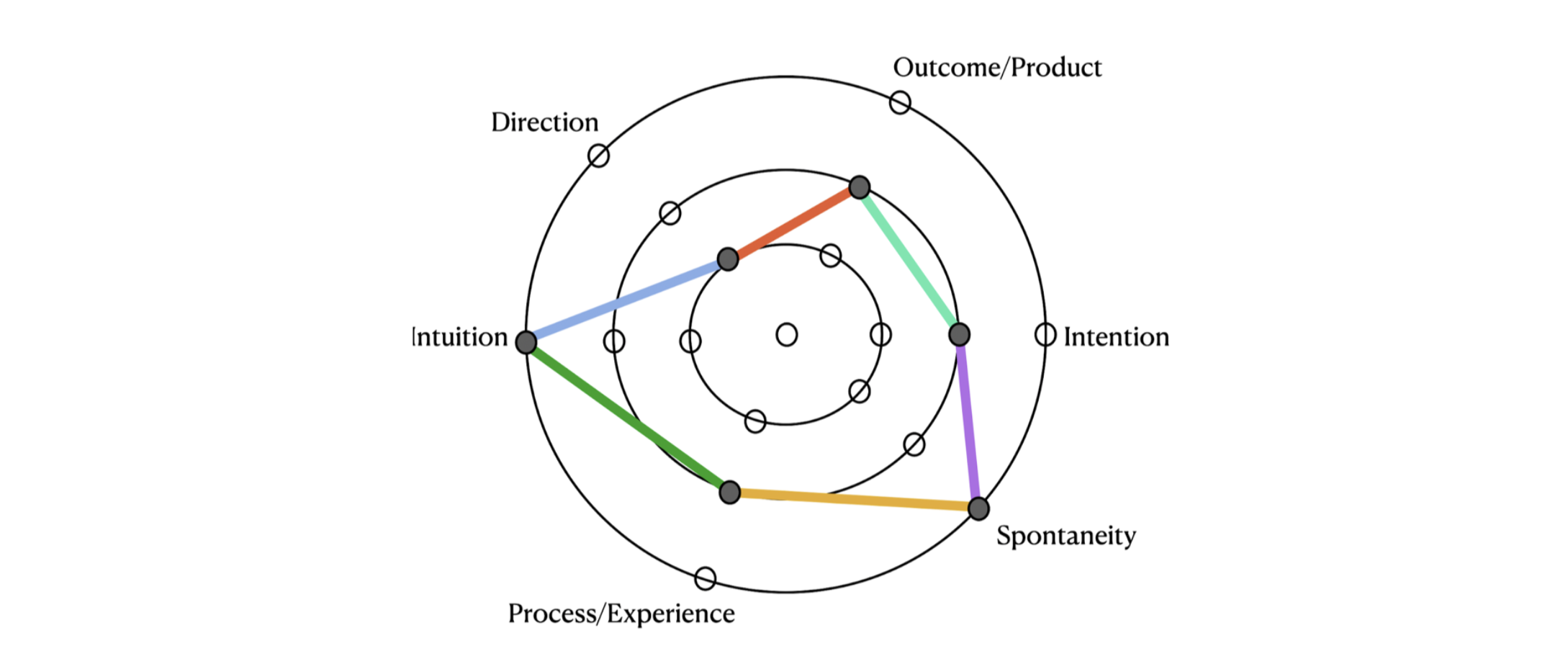

This can be visually displayed in the following diagram, indicating how different elements are in play — the further from the centre, the more prominent the effect of one element. This one, representing Episode 3, indicates that there was a small degree of premeditated direction, and a more prominent role of spontaneity. One can argue that this is a summative approach to a performance as a whole, while at any one moment the lines and dots — and the shape it produces — evolves. This model is based on whisky tasting wheels; the newcomer sees the shape as abstract, while the veteran finds more meaning in the shape, armed with memories of past experiences. The same exists, we argue, for interdisciplinary experiments, and therefore why a visual model may be communicatively effective.

Figure 10: Model for improvisatory interdisciplinary collaborations

Figure 11: Evolving levels of interaction and interplay

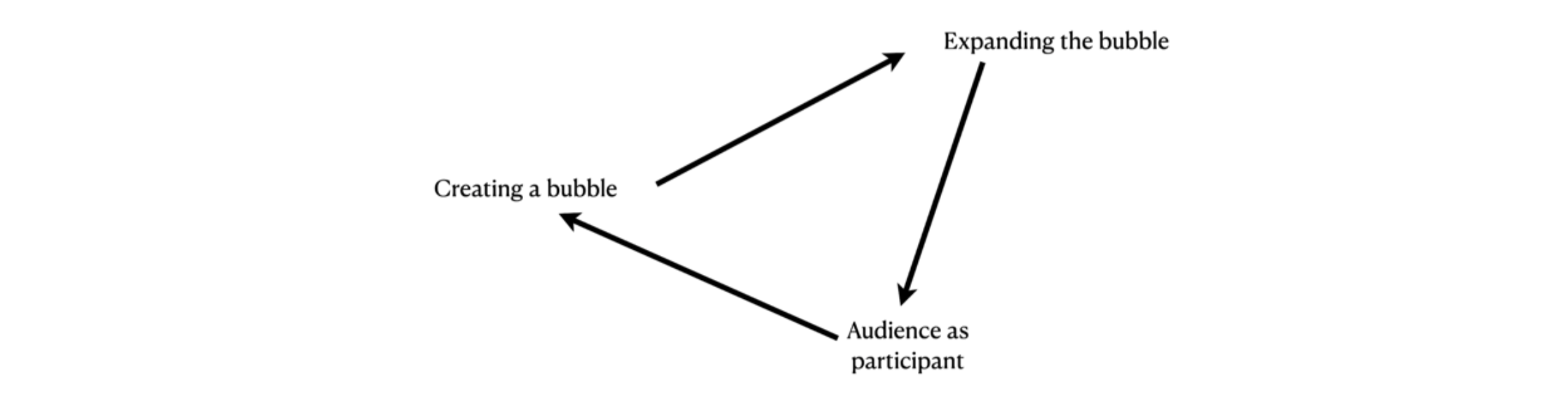

Finally, another set of parameters to consider is how the performative nature plays a role, as seen below. The painter has the smallest bubble — by default, her art form is done in isolation. Expanding the bubble for her now encases a musician, then a videographer, then another musician. For musicians, the original bubble may be larger, at least with another performer, and in many cases, with videography. The expansion is to include interaction with another art form — here, the visual art of painting.

The further inclusion of an audience, even when not directly interactive, creates a new participant, and has the pull of the performative nature — not just the adrenaline of a live performance that all musicians experience, but the complication of doing this within a purely improvised setting, and dealing with the earlier interplay of moving along the spectrum of intention and intuition. The effect of the audience can push one unintentionally towards being more contrived, to present to the audience patterns of logic and order. The newest member of our team decided to intentionally not follow the other musician at times, in order to prevent the predictable — in not following the fellow musician in moving closer to the painting, as well as in not picking up two triangles that were brought in for contrasting sonic effect. One could say, then, that she created a new bubble, within the wider one.

We end this discussion by returning to our earlier description of whether this is experimental collaboration or a collaborative experiment. In the spirit of our circular model, we can say that it is both, and it is in that adventure and growth from one episode to the next that we play, with discipline, in The Garden of Sight, Sound, and Surprise.

[1] Alyse Guler and Valerie Ross, “Exploring Musical Intersections in Visual Arts: Visualising Electroacoustic Sounds via A/r/tographic Inquiry”, Musical Intersections in Practice 2021, http://cimacc.org/musical-intersections-in-practice-2021/ (pages 49-58).

[2] Ibid, 57.

[3]Ibid., 53.

[4] Miguel Jerónimo et al. “AffectiveWall: An intermedia instrument for affective generation of music and paintings

through gestural expressivity” https://fenix.tecnico.ulisboa.pt/downloadFile/395143161273/resumo.pdf

References

Burke, R. & Onsman,A. (2017) Perspectives on Artistic Research in Music, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Crispin, D. ‘Artistic Research as a Process of Unfolding‘, Norwegian Academy of Music, 3 (2019) https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/503395/503396

Guler, A. and Ross, V., “Exploring Musical Intersections in Visual Arts: Visualising Electroacoustic Sounds via A/r/tographic Inquiry”, Musical Intersections in Practice 2021, http://cimacc.org/musical-intersections-in-practice-2021/ (pages 49-58).

Jerónimo, M. et al. “AffectiveWall: An intermedia instrument for affective generation of music and paintings through gestural expressivity” https://fenix.tecnico.ulisboa.pt/downloadFile/395143161273/resumo.pdf

McDonnell, M. “Visual Music” eContact! 15:4, Canadian Electroacoustic Community, 2014. https://www.econtact.ca/15_4/mcdonnell_visualmusic.html

Nelson, R. (2013) Practice as Research in the Arts, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nikolaj Hess, “Transformative Reflections”, Rhythmic Music Conservatory, Copenhagen, 2023. https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/882976/2089352104