PULSE VOL.5 NO.1 (August 2024-January 2025)

LATERAL PRACTICE AND DECENTRALIZED SOUND: REFLECTIONS ON CHIANG MAI’S SONIC ART SCENE FROM THE 2010S TO THE PRESENT

-Thatchatham Silsupan

Abstract

This paper briefly examines sound-based art practice in Chiang Mai from the 2010s to the present, focusing on its socio-political dimension and departure from centralized, institutional aesthetics. Central to this discussion is the concept of what I refer to as “lateral practice,” an approach where aesthetico-localized experimentation, collaboration, and adaptability take precedence over traditional methods that prioritize technical proficiency and, more importantly, strict adherence to established disciplines. Through examining key works by Chiang Mai local sound artists such as Anusorn Tunyapalit, Anurak Tunyapalit, and Arnont Nongyao, I reflect on how lateral practice could challenge centralized aesthetics, provide spaces for cultural resistance, and create dialogue through socially engaged commentary. This paper, developed from my panel discussion “Sound and Singularity” at PGVIM International Symposium 2024, also positions sound-based art practice in Chiang Mai as a vital framework for rethinking sonic art’s role in addressing power dynamics and promoting collective agency in a localized context.

Keyword: lateral practice, sound/sonic art, Chiang Mai’s sound artist

Introduction

A few years back, I had a chance to attend a concert called “October Sound,” curated by Superimposition–a local artist-run initiative who refers to themselves on the Facebook page as “Biotechnology Company.” At first, it seemed to me like it was just another evening event in a familiar subcultural space–a lively blend of noise music, experimental sounds, harsh beats, EDM, dancing, drinking, smoking, karaoke, and live VJing. It appeared nonetheless to be nothing more than an annually carefree celebration of the local youths. However, as I stood there absorbing the atmosphere, I soon began to realize there was much more to the event than a typical jam session. The flashing lights, visceral beats, and chaos were not merely for entertainment but a powerful outlet for these young people to express themselves, be heard, and resist the challenging circumstances they had encountered over the past decade. Besides, it is important to note that these were young individuals who had, for years, endured the consequence of centralized politics, a monopolized economy, and a militaristic culture deeply ingrained in Thai society. If you have followed the turmoil of Thai politics in recent years, you would recognize these youths as those whose voices have been consistently suppressed and often muted by the authorities.[1]

To some extent, the event, for me, eventually became a temporal enclave in which these young people could come together to share and release their frustrations though whatever creative means they had at their disposal. Notably, I recall one particular moment: thick smoke covered the stage as fire erupted spectacularly, almost consuming the audience whole. As I felt the heat and its energy, I could sense the anger and urgency that was being released. Consequently, the stage literally turned into a battleground where the suppressive voices and oppression clashed.

Context

In a larger context, the aforementioned concert can be a starting point for understanding how art, especially sound-based art practice, has developed in Chiang Mai over recent years. Unlike Bangkok’s centralized, institution-driven creative sector, Chiang Mai’s art community is often characterized by informality and self-organization- traits that reflect broader efforts across Thailand to decentralize cultural production and challenge Bangkok’s dominance as the nation’s cultural hub. [2] Thus, experimental and independent spaces play a crucial role in shaping the artistic landscape in this community. These makeshifts, often socially engaged, artist-run networks promote a more fluid, organic, and locally driven sound-based art practice, moving away from the mainstream, Eurocentric approach. Furthermore, as sound artists in Chiang Mai do not often rely on centralized institutional support and its inclination toward institutionalization, their practices have been developed into what I would refer to as “lateral practice”–an approach in which aesthetico-localized experimentation, collaboration, and adaptability take precedence over traditional methods that prioritize technical proficiency and, more importantly, strict adherence to established disciplines. This lateral practice, as I propose, also resonates with Pedro J. S. Vieira de Oliveira’s concept of decolonizing sound art, which advocates situating sound practice within political, social, and historical contexts, rather than treating it as an abstract phenomenon. [3] It also emphasizes the need to move away from Western-dominated narratives in sound by engaging with marginalized voices and their unique sonic allowing them to secure a presence within a predominantly centralized field, while fostering resistance and reclaiming agency. To better understand the current artistic landscape, it is important to discuss and contextualize Chiang Mai’s art scene by tracing its origins. In the 1990s, the Chiang Mai Social Installation (CMSI) movement emerged as a transformative force, laying

Figure 1: October Sound, 3 December 2022

the groundwork for socially engaged art practice that emphasize the aesthetico-localized qualities of art in the area and the region. Driven by a group of artists and art students, CMSI sought to bring art and creative practices into the public sphere by employing social, participatory art as both strategy and tactic. Consequently, they turned public spaces–such as temples, markets, streets, schools, courtyards, and abandoned buildings–into impromptu stages where ordinary people could apply creative thinking in their area of specialization, somewhat akin to Joseph Beuys’ concept of “social sculpture.” [4] Thus, this creates a space for negotiating and challenging the rigidity of the creative class and their monopolized artistic practice.The spirit and legacy of CMSI remains a strong testament to today’s Chiang Mai contemporary art landscape albeit in, though expressed in different forms and sometimes even contested. [5] From my own experience, I have observed that CMSI’s emphasis on making art accessible and advocating for social justice, equality, and freedom has clearly influenced several local artists and art students. Their artistic legacy is evident in how local artists approach their medium, extending beyond mere aesthetic expression to serve as a powerful tool for social critique and commentary. Simply, put CMSI’s influence has encouraged local artists to think about art not merely as visual or auditory spectacle, but also as a tool for driving social change.

Local artists and their artworksHistorically, sound has evolved into a powerful medium. For example, noise, field recordings, sonic archives, and DIY electronics have become tools that sound artists frequently employ to challenge established norms, traditional practices, and centralized aesthetics. Similarly, for Chiang Mai’s sound artists, coinciding with the influence from the CMSI and lateral practice sound-approach, this notion transcends artistic goals; it becomes an act of reclaiming spaces for marginalized voices. Everyday sounds and noises are transformed into socio-political statements or inquiries. From this perspective, I aim to discuss and reflect on the works of the local artists who, in my view, exemplify the most compelling sound-based art practices in recent years.

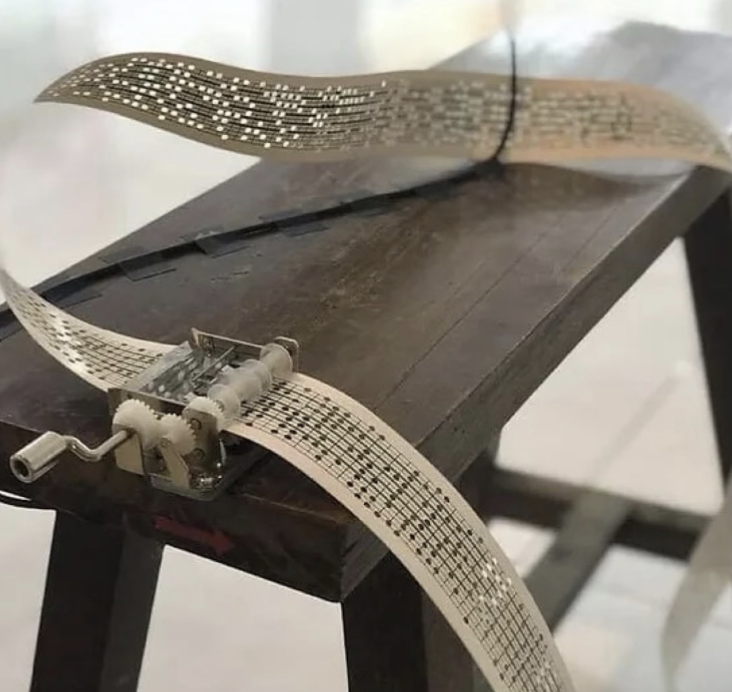

The first work is a sound installation by Anusorn Tunyapalit titled “ทน345bkk_7116,” created in 2018.6 In this work, Anusorn transformed a letter written by Nuamthong Paiwan–a taxi driver who took his own life in protest against the 2006 military coup in Thailand–into a sound installation. The letter was, in fact, a suicide note, written after Mr. Paiwan was mocked by the authorities who claimed no one would die for their principles, especially for freedom and democracy. This statement came in response to Mr. Paiwan’s act of crashing his taxi into a military tank during the coup d’état. Reflecting on this tragic event, Anusorn carefully transcribed the letter into Braille and sonified it using his DIY music box. This artistic choice highlights the use of auditory and tactile media to critique the state’s silencing and abuse of power. According to the artist, Braille serves as a metaphor for the blindness imposed by the Thai government, where dissenting voices are often deliberately erased from public discourse. Additionally, the mechanical sound of the music box, filled with grinding noise, reinforces the harsh reality of suppressed voices struggling to break free from the layers of power relations. Consequently, the interplay of these elements offers a new form of narrative, where sound sound, as a central character, seeks to reclaim its place, turning deeply personal acts of dissent into shared, collective experiences. From my direct encounter with the work, as the sound installation echoed through the hall, I couldn’t help but notice how the piece persistently drew listeners into engaging with intricate layers of sound, visuals, and meaning. As a result, it transformed the act of listening into a confrontation, where memory and resistance converge, amplifying the voices of the silenced and urging a contemplation of contemporary Thai politics.

Figure 2: Anusorn Tunyapalit’s “ทน345bkk_7116” Video 1: https://vimeo.com/user38715077

Next is a sound installation by Anusorn’s twin brother, Anurak Tunyapalit, titled ‘ยีโดะระ’ (pronounced: Yi-Do-Ra), which was created in 2022. [7] The title of this piece translates literally to ‘far away’ in the Karen language, conveying an ironic narrative about the proximity and distance imposed by modern nation-states along borders. These borders disrupt shared cultural and historical ties, highlighting the paradox of being simultaneously near and distant. Recognizing sound’s inherent ability to transcend physical and political barriers, Anurak uses sound to explore themes of distance, borders, and the limitations of communication. He then modified a radio to capture hidden frequencies, tuning into the voices, sounds, and music transmitted by ethnic communities communicating across the borders of Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, and Southern China. As a result, the radio waves carrying these sounds effortlessly transcend boundaries, challenging state-imposed restrictions and symbolizing the permeability of communication and relationships. This disruption of rigid nation-state borders creates a new form of connection, highlighting the fluidity and nuance of human interaction. Experiencing the piece firsthand too, I was fascinated by how it navigated sensitive political terrain, the “Zomia”, with a unique sense of poetry, especially at a time of unresolved ethnic tensions and the expansion of the controversial Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Additionally, it encourages listeners to reflect on how political borders fragment communities, despite their shared histories and cultures. Yet, “Yi-Do-Ra” exemplifies the politics of listening by transforming the act of tuning into distant voices into a profound gesture of harmony, challenging the state’s tight control over transmitted communication.

Figure 3: Anurak Tunyapalit’s “ยีโดะระ” (Yi-Do-Ra)

Last but not least is a work by Arnont Nongyao, a media artist with whom I have collaborated on various socio-political art projects through an artist-initiative, “Chiang Mai Collective. From his pinky, mobile instrument “Bicycle Soundy (2015-16),”to the looped soundscape of local flea markets “Opera of Kard (2019-21), or the collaborative DIY electronic wastes-sonic sculpture “a Weirdo the Last Music Box (2023), Arnont’s sound-based art practice directly embodies the notion of lateral practice by employing sonic experimentation and the holistic creation of artwork from locally sourced electronic parts and materials, his work challenges the Euro-centric practice of sound-based art.

Figure 4: Arnont Nongyao’s “Pinky Soundy Bicycle Roaming in Yokohama”

Figure 5: Arnont Nongyao’s “a Weirdo the Last Music Box”

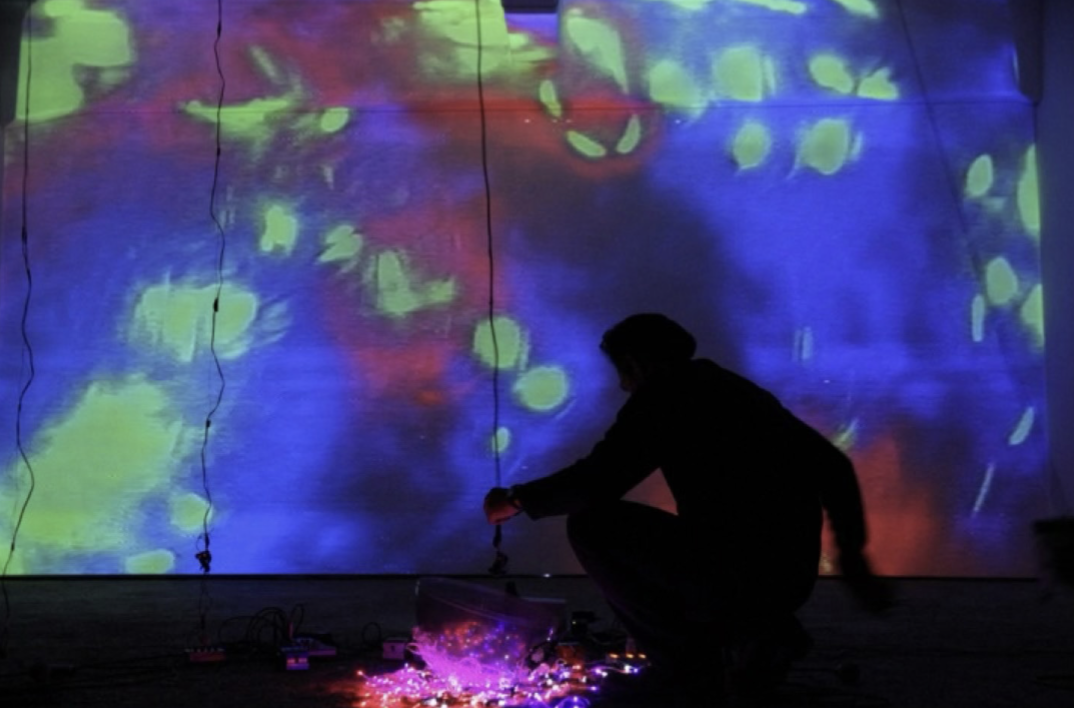

One of Arnont’s notable work, “Drink Sky On Rabbit’s Field (Funeral Song for Nothing),” created in 20158 , explores the contradiction of life and death through the interplay of sound and light. The audiovisual performance, which combines experimental sound and moving images, features Christmas-like light–objects that hold significant meaning in Thai culture, used in both celebratory and funerary contexts. These objects create an atmosphere that disorients and challenges the distinction between festivity and mourning. The piece unfolds by revealing layers of sound from a traditional Thai funeral, punctuated by bursts of gunfire and various mechanical noises. Hence, it confronts the audience with the unsettling persistence of violence and taboo within socio-political systems. As the artist stated in his charmingly broken English: “When the time we will drink sky coming we will listen to a funeral song composed by bullet’s sound and repeat ___ round that for nothing and after that we will compose a new song together. We will look at the sky inside our body and share to each other for the public song” [9]

Additionally, his mastery in juxtaposing joyful lights with melancholic sounds creates an unsettling experience, compelling listeners to confront the paradox inherent in societal rituals. The sound of gunfire further critiques state-sanctioned violence and serves as a reaction to the oppressive mechanisms through which the state maintains control. In this sense, Arnont’s work transcends a mere reflection on mortality, evolving into a powerful commentary on institutionalized oppression.

In my conversation with the artist, he explained how the piece reconfigures the performance space into a site where personal grief intersects with the collective struggle, engaging with the notion of art’s transformative social function. Reflecting on this, much like the concert I attended earlier, the stage becomes a space of resistance, demonstrating how sound and light can extend beyond aesthetic invention to deeply engage with the socio-political fabric of Thai society. Through this performance, Arnont invites the audience to reflect critically on rituals and structures of power that avoid our daily lived experience.

Figure 6: Arnont Nongyao’s “Drink Sky On Rabbit’s Field (Funeral Song for Nothing)”Video 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5P2tLdac0R0

Since I mentioned Arnont, I would also like to briefly discuss my recent work, A Gift–from Arnont for Tacet(i) (2023), which is deeply connected to his ideas and influences on my practice. Similarly, this work embodies the concept of lateral practice found in Arnont’s works and those of the previously discussed artists. In this piece, I revitalized Arnont’s DIY mobile instrument, which was once a performative tool, transforming it into an installation in the same room where it was struck and plucked ten years ago. Additionally, I combined the instrument with live digital projection and Gerald P. Dyck’s forgotten sonic archive of traditional Lanna Song. In this sense, it invited the listener to reflect not just on the interplay between sound and visuals but also on the layered meaning tied to cultural memory and collaboration. This approach opened a dialogue around the relational and intertextual dimensions of artistic practice, although not directly serving as a socio-political commentary. Finally, by presenting the piece with a fixed duration and without the notational composition typical of concert-based New Music settings, I challenged the conventional hierarchical aesthetics of Euro-centric practice by integrating localized narrative and temporal, collaborative processes. “Dedicating this piece to Tacet(i), a renowned Thai contemporary music ensemble, further underscores its communal essence, shifting the focus from individual authorship to a shared, holistic artistic experience.

Figure 7: Thatchatham Silsupan’s “A Gift—from Arnont for Tacet(i)”

Conclusion

The concept of lateral practice is vital to sound-based art practice of Chiang Mai’s local artists. It emphasizes aesthetic-localized experimentation, collaboration, and adaptability, focusing on sound-based art as a practice rooted in context rather than the abstract materiality of sound. As an approach, lateral practice highlights the potential of sound to emerge through direct interaction with the local socio-political landscape. Thus, the inherent resistance of sound to containment aligns perfectly with this ethnos, allowing artists to create works that challenge aesthetic and social conventions––as shown and discussed in Anusorn, Anurak, and Arnont’s works. This also not only helps dismantle existing hierarchies and centralized aesthetics but also fosters spaces for new dialogues and communal engagement. Another concept that also strongly resonates within me regarding this issue is Deleuze and Guattari’s idea of “deterritorialization and reterritorialization.” Deterritorialization–the process of breaking free from established norms–is evident in how Chiang Mai local artists reinterpret Euro-centric, Western-dominated definition of sound-based art practice. They incorporate these definitions into their own cultural and political contexts, reframing them in ways that challenge their original meanings. Notably, none of the aforementioned artists have attended formal sound art or music programs, underscoring their departure from institutional norms. Following this, reterritorialization occurs as these fragmented elements are reassembled to reflect the unique socio-political realities of Thailand. The result is a hybrid form of expression that is both deeply rooted in local experiences and broadly relevant in global discourse. Moreover, the decentralized nature of Chiang Mai’s art scene, with its focus on sound-based art practice and lateral modes of engagement, offers a powerful model for how contemporary art can thrive outside of institutionalized and centralized aesthetics. The artists mentioned utilize sound as a transformative medium, demonstrating art’s profound capacity to drive social and political change. They actively engage with and challenge the socio-political issues imposed upon them. Their work amplifies voices that are often silenced by dominant structures and forms dialogue that rejects exclusionary norms. In a country where cultural politics remain largely centralized in Bangkok, the practice of Chiang Mai’s local artists perhaps could represent a nuanced and effective form of resistance.

To conclude, I want to end this writing with an excerpt from a Facebook post. This post possibly says everything about art and artists in Chiang Mai, albeit in a very cynical way: “Art exhibition in Bangkok: Adorable, heartwarming illustrations, Instagram-worthy. Art exhibition in Chiang Mai: Politics, activism, radical resistance. Chiang Mai is truly intense!”

Figure 8: A random Facebook post compairing art exhibitions between Bangkok and Chiang Mai

[1] For further context, see: Nutcha Tantivitayapitak and Sudarat Musikawong, “Artn’t: Thailand’s Rebel Artists,” Arts Equator, 18 January 2023,

https://artsequator.com/artnt-thailand/.

[2] Gridthiya Gaweewong, “Decentralizing the Bangkok-centric Art Scene,” The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation, 16 October 2012,

https://www.guggenheim.org/articles/map/decentralizing-the-bangkok-centric-art-scene

[3] Pedro J.S. Vieira de Oliveira, “Dealing with Disaster: Notes toward a Decolonizing, Aesthetico-Relational Sound Art.” In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Sound Art, ed. Sanne Krogh Groth and Holder Schulze (Bloomsbury Academic, 2020), 71-88.

[4] Thasnai Sethaseree, “The Po-Mo Artistic Movement in Thailand: Overlapping Tactics and Practices.” Asian Culture and History 3, no. 1 (2011): 36-38.

[5] For further context, see: Simon Soon, “Images Without Bodies: Chiang Mai Social Installation and the Art History of Cooperative Suffering,” Afterall, 20 September 2016, https://www.afterall.org/articles/images-without-bodies-chiang-mai-social-installation-and-the-art-history-of-co-operative-suffering/. Here is my thought: Although the CMSI was instrumental in decentralizing Thai contemporary art, challenging Bangkok’s dominance as the cultural hub and positioning Chiang Mai as a critical space for alternative art practices through socio-political commentary, its emphasis on critical regionalism and resisting global trends might unintentionally create its own form of exclusivity. A recent panel dis-cussion at Synthopia: Symposium on Media Arts and Design 2024 attempted to revisit CMSI’s legacy. Titled “1990s: A Critical Re-examination of the Golden Era of Art,” the panel invited key figures from CMSI to reflect–or perhaps lament–the so-called “golden era.” The discussion focused on one dimension of art practice: its role as socio-political instrument, raising questions among current local practitioners and students who advocate for more open-minded and diverse approaches. These newer approaches often integrate technology and engage with global trends, highlighting a potential tension between past and present paradigms of art practice. During the Q&A, an online audience member questioned the authority of a panelist who criticized the current state of local art practices as lacking in comparison to those of CMSI artists. The audience member asked whether he had sufficiently engaged with current practices and whether his critique implied an attempt to dominate aesthetics.

[6] Anusorn Tunyapalit, ทน345bkk_7116, 2018, sound installation, https://shu22moo.wixsite.com/artwork/345b-70

[7]Anurak Tunyapalit, ยีโดะระ, 2022, sound installation, https://plus.thairath.co.th/topic/subculture/104141.

[8] Arnont Nongyao, Drink Sky On Rabbit’s Field (Funeral Song for Nothing), 2015, sound and moving images performance, http://www.arnont-nongyao.com/Tokyo_wonder_site_Funeral_song_for_nothing.html.

[9] Tokyo Arts and Space, 17 November 2024, https://www.tokyoartsandspace.jp/en/archive/exhibition/2015/20151204-5889.html

References

Gaweewong, Gridthiya. “Decentralizing the Bangkok-centric Art Scene.”The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation. 16 October 2012. https://www.guggenheim.org/articles/map/decentralizing-the-bangkok-centric-art-scene.

J.S. Vieira de Oliveira, Pedro. “Dealing with Disaster: Notes toward a Decolonizing, Aesthetico-Relational Sound Art.” In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Sound Art, edited by Sanne Krogh Groth and Holder Schulze, 71-88. Bloomsbury Academic, 2020.

Nongyao, Arnont. Drink Sky On Rabbit’s Field (Funeral Song for Nothing). 2015. sound and moving images performance. http://www.arnontnongyao.com/Tokyo_wonder_site_Funeral_song_for_nothing.html.

Sethaseree, Thasnai. “The Po-Mo Artistic Movement in Thailand: Overlapping Tactics and Practices.” Asian Culture and History 3, no. 1 (2011): 36-38.

Soon, Simon. “Images Without Bodies: Chiang Mai Social Installation and the Art History of Cooperative Suffering.” Afterall. 20 September 2016.https://www.afterall.org/articles/images-without-bodies-chiang-mai-social-installation-and-the-art-history-of-cooperative-suffering/.

Tantivitayapitak, Nutcha, and Sudarat Musikawong. “Artn’T: Thailand’S Rebel Artists.” Arts Equator. 18 January 2023. https://artsequator.com/artnt-thailand.

Tokyo Arts and Space. 17 November 2024. https://www.tokyoartsandspace.jp/en/archiveexhibition/2015/20151204-5889.html.

Tunyapalit, Anurak. ยีโดะระ. 2022. sound installation. https://plus.thairath.co.th/topic/subculture/104141.

Tunyapalit, Anusorn. ทน345bkk_7116. 2018, sound installation. https://shu22moo.wixsite.com/artwork/345bkk-7116.78