PULSE VOL.2 (September 2022)

F(r)ee Road:An Artistic Research Audiovisual Project

Abstract

This paper explains the author’s artistic process in creating an audiovisual project with a social message called F(r)ee Road. The project is a game-based composition for one player in which the player controls a user-object and tries to avoid collisions. The work is founded on two concepts: glitch-art, an aesthetic of error used to create both visual and sound modifications; and data sonification, the conversion of data to non-speech sound. All processes were created by personal computers using the Max, a software program created by Cycling 74. This work is a contribution to the blossoming field of sonification-based art.

Keywords: Audiovisual, Glitch, Sonification

1. Noise in Composition

Music marks time in this small circle and vainly tries to create a new variety of tones. We must break at all cost from this restrictive circle of pure sounds and conquer the infinite variety of noise-sounds.

—Luigi Russolo, The Art of Noises [1]

Russolo’s comment, penned in 1913, speaks to an important aesthetic turn in the history of what we call “classical music.” The creative potentials of traditional, tonal models, reached its apex in the Romantic era with the works of composers such as Richard Wagner and Johannes Brahms. Composers of the next generation, such as Claude Debussy, Erik Satie, Igor Stravinsky, and Arnold Schoenberg, found ways to create musical meaning through new combinations of tones and sonic colours. Works by these great artists continue to influence composers today. Russolo, however, encouraged composers to go further still. He spoke to a borderless conception of musical creativity, wherein all sound can be musical content. In his opinion, modern composers should not restrict themselves merely to conventional instruments, but should instead embrace the larger infinite variety of all possible sounds.

Sounds in the real world exceed the frequency range of conventional musical instruments. For example, the pitches produced by a piano range from A0, the lowest key, to C8, the highest. This corresponds to the frequency range of 27.5 Hz to 4186 Hz. [2] Humans, however, are able to perceive sounds from a far wider range: about 20Hz to 20,000Hz. Russolo asks, why not break through the limits imposed by traditional instruments in order to find new modes of expression? Why not allow the infinite variety of sounds we hear daily in the real world into the composer’s musical palate? The conventional palate previously open to composers (here I refer to pitched instruments only, as percussion instruments are a different matter) is much more narrow.

Russolo’s aesthetic can be found not only in electronic music such as musique concrète, but also in the works of modern composers like Helmut Lachenmann, who developed novel sonic processes for compositions (see, for example, his Pression for solo cello). Today, it is widely recognized that Rossolo’s aesthetic vision greatly expanded musical potential for modern composers.

2. Glitch, the Aesthetic of Failure

We are all familiar with glitches. They are especially ubiquitous on the internet. In technical domains such as electrical engineering, a glitch is defined as a “sudden, usually temporary malfunction or fault of the equipment.” [3] Glitch artists exploit these technical errors to disfigure sources, such as the information coded in images, to create new meaningful outcomes. [4] Glitch art thus involves both material foundations and changes to the media, or to the processing of digital media.[5]

Glitch art developed following the advent of the camera. The camera can more faithfully reproduce reality than a painting can. Who needs a portrait painted when the camera can create a more “realistic” result? The camera spurred visual artists to move into new territories. Impressionism, cubism, and futurism, for example, developed in the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in part, in response to the development of the camera. Pablo Picasso, for example, explores the human body through geometric forms, and Claude Monet used unique drawing techniques to capture the visual essence of a fleeting moment. These artists played with distortions of reality. Their work does not present direct representations. In the modern era, the representation of reality is no longer essential. In the 1960s and 70s, the artist Nam June Paik Not was one of the first artists to apply an aesthetic of glitches. In his work Magnet TV, for example, he placed a magnet over a TV to distort the original signal. Within the musical domain, glitch aesthetics have long played a significant role in electronic music. [6] From the 1990s onward, artists in various domains have applied the aesthetics of error to their creative work. Among the leading musicians to employ such techniques are the music group Aphex Twin and the audiovisual artist Ryuji Ikeda. This aesthetic of error inspires me as well, and was the springboard for my current work. The basis of my composition aesthetic is the transformation of a given source into a new form.

Benefits of incorporating Music in Intervention

A study was conducted in 2006 on the effects of music-listening intervention in enhancing the effects of analgesics, decreasing perceptions of depression and disability, and promoting beliefs of personal power.7 A total of 60 recruits with chronic non-malignant pain (CNMP) participated in and completed a randomized controlled clinical trial where they were randomly assigned into a standard music group (n = 22), a patterning music group (n = 18), or a control group (n = 20) that did not receive any music-listening intervention. All participants had a preliminary baseline test across several evaluation tools: feelings of power were measured through the Power as Knowing Participation in Change Tool version II (PKPCT II), perceptions of pain were measured through the McGill Pain Questionnaire and Visual Analogue Scale, perceptions of depression were measured through the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, and perceptions of disability were measured through the Pain Disability Index. Participants that received the music- listening intervention were assigned to listen to music for one hour everyday for one week. All participants were tasked to keep a diary for the seven-day observation period.

The standard music (SM) group was assigned to listen to a choice of tapes that were predetermined by the researchers. The patterning music (PM) group was asked to listen to upbeat, familiar, instrumental, or vocal music of their choice. All participants were evaluated again after their seven-day observation period as a post- test. The results showed that groups that utilized music-listening interventions had statistically significant effects in having more feelings of power, and less perceived pain, depression, and disability compared to the group with no intervention.

There were no statistically significant differences between the SM and the PM group, contrary to the researchers’ initial expectations of the PM group performing better than the SM group.7 This study shows that simply listening to music has a significant effect on reducing pain and depression for patients with long-term conditions, suggesting its potential in improving their quality of life if regularly practiced.

3. Sound Generative through Sonification

Sonification is the use of non-speech audio to convey information.

—Gregory Kramer, “Auditory Display: Sonification, Audification and Auditory Interfaces.”

The above epithet is an early definition of sonification. Originally, sonification was not intended for artistic purposes. The main use was instead to convey scientific information, such as notifications and alarms. More recently, a comprehensive definition that references sonification’s artistic potential was given by Liew and Lindborg,

Sonification is any technique that translates data into non-speech sound with a systematic, describable, and reproducible method, to reveal or facilitate communication, interpretation, or discovery of meaning that is latent in the data, having a practical, artistic, or scientific purpose. [8]

The transformation of any type of data into sound can be sonification. It is up to the user to decide how to employ it. For artists, sonification provides yet another opening up of possibilities. The potential for creation is infinite.

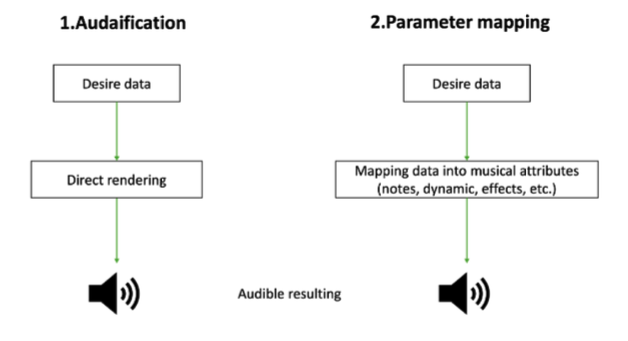

Sonification can be accomplished through a variety of techniques—audification, iconic sonification, earcon, parameter mapping sonification, and model-based sonification to name a few—and new techniques and possibilities are always being developed. For F(r)ee Road, I used two techniques: audification and parameter mapping (see figure 1). Kramer defines audification as “the direct playback of data samples,” ordered in time but allowing for direct transformations such as time compression. [9] One of the most well-known works using audification is Chris Hayward’s Listen to the Earth Sing. In this work, Hayward implements direct sonification (audification) on seismic-data and displays the sounds as a result.[10] Parameter mapping is simply the mapping of any data onto any auditory parameters, such as pitch, dynamics, or rhythm. It is a common technique used in many fields of research and in the sonic arts.

Figure 1 Diagram of sound generation through sonification.

4. Compositional Process

The direct inspirations for the F(r)ee Road project was the work Formula Minus One, a multimedia composition for violin and video by Marko Ciciliani that incorporates videos of a Formula One car race. [11] The violinist interacts with live-electronics and live-video elements. Although my work and Ciciliani’s share some similarities, the musical aesthetic of the two are different. F(r)ee Road also draws on the experimental music of Earle Brown, who composed what he called “mobile” music—music in which specific elements are fixed but the occurrences or the chances of various events changes from one performance to the next, dependent on chance events, such as wind blowing on a mobile.

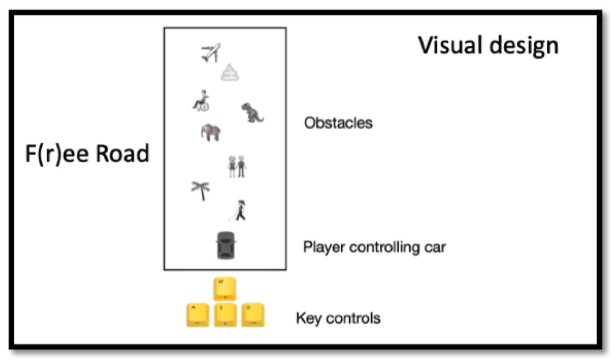

F(r)ee Road is scored for one performer. And this performer need not have any formal musical training as the only skill required is the ability to operate a laptop computer. All the programming processes for F(r)ee Road were written on Max, a software program created by Cycling 74. The computer acts as a hyper-musical sound generative device with sounds generated through the sonification procedures discussed above, based on data drawn from the live-video source. Below I discuss the three basic elements of the work: visual design, sound generative procedures, and composition rules.

First, the visual design. The object “car” is physically controlled by the player through the computer keyboard while various “obstacles” serve to prompt musical and visual events.

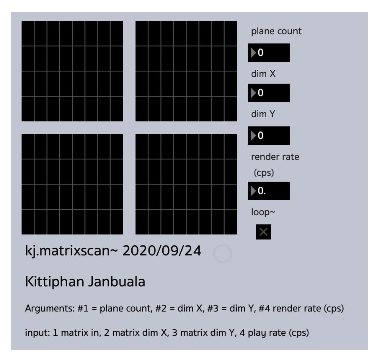

Secondly, the sound generative procedures. The visual design is converted into sounds through audification. Specifically, visual color data is translated into sounds (see figure 2). The outcomes of this process are unpredictable rhythmic events and an un-periodic waveform, which mostly produce noise. Additionally, parameter mapping sonification is applied to the car’s movement. The object’s location is mapped to two oscillators with frequency modulation that imitates the roar of an engine.

Figure 2 Custom sonification patch. The purpose of the patch is to extract color data for parameter mapping sonification and audification.

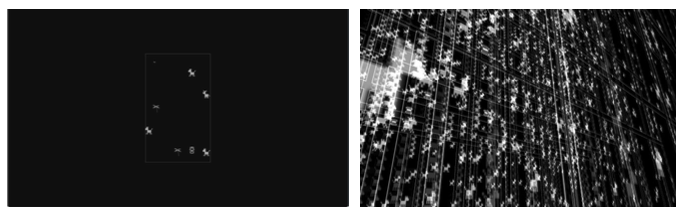

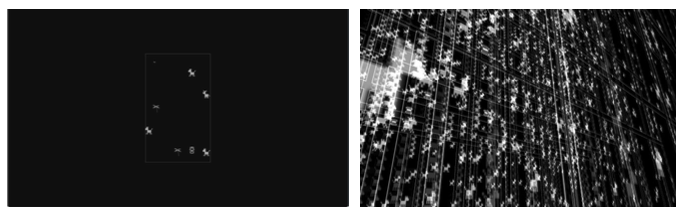

Thirdly, the composition rules. The composition is based on Brown’s concept of mobile music discussed above. The basic condition for the composition is designed as follows: a collision between the car and an obstacle affects both the generative function and the visual modification (see figures 3 and 4). With these collisions, the aesthetic of malfunction, or glitch, is employed. Each collision between the user’s object and the obstacle causes an abrupt, random change, such as a sudden enlargement of the obstacle-object (see figure 3), screen rotation, or a loss of control of the player’s object.

The piece consists of 12 levels, each of which is one minute in length. The higher the level, the more obstacles there are, and the faster the car moves.

Figure 3 Left: the original video output.

Right: glitch-video after collision with an object.

Figure 4 The video design and object-controlling design plan.

5. Social Significance

F(r)ee Road is designed to be purposefully tedious for listeners—at least at first. The piece is about a repetition of noisiness, and the visual elements are rather static. Yet, the tedium will fade as time passes and audiences reflect and discover the social message of the work. What is F(r)ee Road? It is a work of art that speaks to the problem of wealth inequality. The car object is a symbol of wealth and the performer is a stand-in for a wealthy individual that is allowed to crash into anything he or she likes without consequence, merely for the pleasure of generating sound events. Most audience members will discover the social meaning hidden in the work toward the end of the piece, if they haven’t already, in the money-flying scene (see video 1).

In sum, “the road is for the rich” is the social meaning of the work. As noted by reporter Hannah Beech in a 2019 New York Times article, “in Thailand, one of the world’s most unequal societies, even roads have a rigid hierarchy, with the poor far more likely to be killed in accidents than the well-off and well-connected.”[ 12] In Thailand, as elsewhere, the wealthy often cause great difficulty for others, whom they may view as mere obstacles. It is a sad reality that the rich can often do as they please without consequence. Is there a cost paid for reckless actions? Is it free? Or does someone else have to pay a fee?

The compositional techniques of audification and parameter mapping sonification enabled me to realize my vision for F(r)ee Road as a socially conscious work of art. Sonification techniques continue to feature prominently in my composition aesthetic. So many possibilities of sonification remain to be explored by myself and others for artistic purposes. Armed with nothing more than a personal computer and a software program such as Max, composers can create sound art using any source data and any sounds found in the real world, or conjured in the composer’s mind. F(r)ee Road is a contribution to the blossoming field of sonification-based art.]

Video 1 Kittiphan Janbuala: F(r)ee Road

[1] L. Russolo, The Art of Noise, trans. Robert Filliou (New York: Something else press, 1967), 6.

[2] C. R. Nave, “The Piano,” http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/Music/pianof.html.

[3] Oxford Dictionary of English, 2nd ed (2010), s.v. “Glitch.”

[4] Rosa Menkman, The Glitch Moment(um) (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011), https://networkcultures.org/_uploads/NN%234_RosaMenkman.pdf.

[5] Michael Betancourt, “Critical Glitches and Glitch Art,” HZ 19 (July 2014), https://hz-journal.org/n19/betancourt.html.

[6] Nick Prior, “Putting a Glitch in the Field: Bourdieu, Actor Network Theory and Contemporary Music,” Cultural Sociology 2, no. 3 (2008): 303.

[7] Gregory Kramer, “Auditory Display: Sonification, Audification and Auditory Interfaces,” in Santa Fe Institute Studies in the Sciences of Complexity (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison Wesley, 1994), 38.

[8] Kongmeng Liew and PerMagnus Lindborg, “A Sonification of Cross-Cultural Differences in Happiness-Related Tweets,” Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 68, no. 1/2 (January 2020): 25.

[9] Gregory Kramer, “An Introduction to Auditory Display,” in Auditory Display: Sonification, Audification and Auditory Interfaces, edited by Gregory Kramer (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1994), xxvii.

[10] Chris Hayward, “Listening to the Earth Sing,” in Auditory Display: Sonification, Audification and Auditory Interfaces, edited by Gregory Kramer. Santa Fe Institute Studies in the Sciences of Complexity (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison Wesley, 1994), 377.

[11] Marko Ciciliani, Formula Minus One, performed by Barbara Lüneburg, 11 November 2015, video, 10:14 min., https://youtu.be/sIgPuD5dcts.

[12 Hannah Beech, “Thailand’s Roads Are Deadly. Especially if You’re Poor,” New York Times, August 19, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/19/world/asia/thailand-inequality-road-fatalities.html.

Bibliography

Betancourt, Michael. “Critical Glitches and Glitch Art.” HZ 19 (July 2014). https://hz-journal.org/n19/betancourt.html.

Ciciliani, Marko. Formula Minus One. Performed by Barbara Lüneburg. 11 November 2015. Video, 10:14 min. https://youtu.be/sIgPuD5dcts.

Hayward, Chris. “Listening to the Earth Sing.” In Santa Fe Institute Studies in the Sciences of Complexity, 369-404. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison Wesley, 1994.

Kramer, Gregory. “Auditory Display: Sonification, Audification and Auditory Interfaces.” In Santa Fe Institute Studies in the Sciences of Complexity, 1-78. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison Wesley, 1994.

Liew, Kongmeng, and PerMagnus Lindborg. “A Sonification of Cross-Cultural Differences in Happiness-Related Tweets.” Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 68, no. 1/2 (January 2020): 25–33.

Menkman, Rosa. The Glitch Moment(um). Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011. https://networkcultures.org/_uploads/NN%234_RosaMenkman.pdf.

Nave, C. R. “The Piano.” http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/Music/pianof.html.

Prior, Nick. “Putting a Glitch in the Field: Bourdieu, Actor Network Theory and Contemporary Music.” Cultural Sociology 2, no. 3 (2008): 301-19.

Russolo, L. The Art of Noise. Translated by Robert Filliou. New York: Something Else Press, 1967.