PULSE Vol.1 (May 2022)

Crossing Borders:

the Transmigration and Transplantation of the Philippine Kulintang Music outside Mindanao

-LaVerne David C. de la Peña*

Abstract

In this essay, I describe the transition of Mindanao kulintang music from a local tradition to a musical artform emblematic of Philippine ethnic and cultural identity among practitioners outside Mindanao. I will look at two parallel streams of the transplantation of this music: one, to the academic centers in Manila and the other, to the Filipino migrant communities in the West coast of North America. In particular, I will discuss the contribution of ethnomusicologists as facilitators of this transplantation as well as that of culture bearers who transitioned to careers as teachers of the music to non-Mindanaon students.

Keywords: Kulintang, ethnomusicology, pedagogy

Kulintang refers to the horizontal gong row composed of tuned kettles found in the Southern Philippines as well as in Borneo, Sumatra and Sulawesi. In Mindanao, the Maguindanao and Maranaw versions, which today are the most popular of the Philippine types, consist of eight gongs. Alternately, the term kulintang is used to refer to the ensemble comprised of the kulintang as the main melodic instrument along with a pair of agung (large hanging gongs), two pairs of gandingan (narrow rimmed gongs), the babandil (small hanging gong) and the dabakan (single headed drum) (Kalanduyan, 1996).

While the Mindanao kulintang is often associated with Muslim populations, the tradition predates the coming of Islam to the islands. The music continued to flourish in the Islamic minority communities in Southern Philippines but has vanished in the Christianized majority of the country with the coming of Spanish colonial forces starting in the 16th century until the late 19th century (Cadar, 1996). As the tradition is practiced in Mindanao, kulintang music is associated with prestigious celebrations such as weddings and circumcision rites, as well as for daily entertainment and leisure. Kulintang performers gain prestige in the community by engaging in competitions held in these public celebrations where the best musicians are named for their skill in various playing techniques as well as stamina (Kalanduyan 1996: i12-14). Apart from these secular contexts, kulintang, music is employed in non-Islamic healing rituals called pagipat that involve trance (Maceda 1984).

Kulintang repertoire is based on named rhythmic modes with their characteristic rhythmic patterns and melodic formulae which act as frameworks for improvisation during performance. The Maguindanao practice divides the repertory into two styles – the older a minuna and the newer, and generally faster modes called a bagu (Liao 2013:5). The transmission of these repertories is by oral and informal means, and aspiring musicians learn by observation and participation.

Virtually extinct in the Christianized populations of the Philippines, interest in indigenous music and dances began among academics fueled by nationalism in the years prior to the Second World War. Under the auspices of the University of the Philippines President Jorge Bacobo, a team of researchers from the University of the Philippines led by Francisca Reyes Aquino embarked on field documentation of songs and dances in various provinces in the country. This enterprise resulted in the publication of Aquino’s Philippine Folk Dances and Games (1935) and Philippine National Dances (1946). Perhaps even more significant, Aquino established the UP Folk Song and Dance Club which performed the music and dances from the data she collected in the field.

Following Aquino’s model of field data gathering and development of performance repertoire, Helena Benitez established the Bayanihan Dance Company at the Philippine Women’s University in 1957. Based on the research and creative work of Lucresia Kasilag, Lucresia Reyes Urtula and Isabel Santos, the troupe developed orientalist versions of the music and dances they gathered in the field. Just a year after its establishment, the Bayanihan debuted at the 1958 Brussels World Fair at the request of none other than Philippine President Ramon Magsaysay. After an enthusiastic reception at Brussels, the troupe embarked on a tour of 39 cities in North America in the following year, even appearing on the popular Ed Sullivan show (Terada 2012: 84). This marked the first time that kulintang music, part of the troupe’s Muslim Suite, would be introduced to Filipinos in the US. In the years to come, Philippine folkloric groups modeled after the Bayanihan would sprout all over the US in areas with huge Filipino populations such as California and Hawaii. Younger Filipino Americans would adopt the kulintang along with the baybayin (ancient Tagalog script) and kali (a Filipino form of martial art using sticks) as emblems of identity.

The Era of Philippine Ethnomusicology

By the 1960s, kulintang music would pique the interest of a new breed of Filipino academics apart from the dance folklorists: the ethnomusicologists. Jose Maceda, who would embark on the pioneering systematic survey of Philippine music in the 1950s at the University of the Philippines, had a particular interest in kulintang music (Dioquino 1982: 131). In 1963, he wrote his PhD Dissertation at the UCLA titled Music of the Maguindanaon in the Philippines wherein he devoted an entire section on the kulintang. Maceda chaired what was then known as the Department of Asian Music at the UP College of Music (subsequently named the Department of Music Research and presently the Department of Musicology). Under Maceda’s helm, the department would build what is until today the largest archival collection of Philippine music which made possible the in-depth study by various scholars. With the intention of disseminating research data to a wide range of readers which included school teachers, professionals and students, the department published a journal in Filipino. Later, these publications would be complemented by a number of recordings of traditional music, including Ang Kulintang sa Mindanao at Sulu (The Music of Kulintang in Mindanao and Sulu), a double LP released in 1977.

Apart from research, the mandate of UP’s Department of Asian Music was instruction. The department handled graduate seminars and undergraduate courses in musicology and ethnomusicology as well as performance classes on Asian instruments for music majors specializing in Western music. For this task, Maceda recruited instructors in Chinese Nan Kuan music, Indian sitar, Javanese gamelan, Kalinga music and Maguindanao kulintang. Whenever possible, he made sure that the instructors were natives of these music cultures. In 1968, he recruited Aga Mayo Butocan, a native of Maguindanao who was then finishing her undergraduate studies in Education in Manila (Liao 2013: 20). Butocan would remain teaching kulintang at UP until the present and would be solely responsible for developing a method of teaching kulintang performance to non-Mindanaon students and institutionalizing the pedagogy of kulintang in the university. I will return to discuss Butocan later in this essay.

Apart from Jose Maceda, other ethnomusicologists will pave the way for the migration of kulintang outside Mindanao. After concluding film documentation of music and dances in various parts of the Philippines in 1966, Robert Garfias returned to the University of Washington and proposed the establishment of a kulintang program at the Department of Ethnomusicology. For this, he invited Usopay Hamdag Cadar, an expert dabakan player who comes from a lineage of Maranaw musicians whom he met while doing fieldwork in Mindanao. Cadar began teaching at UW in 1968, marking the introduction of Maranaw kulintang on American soil. He would later earn his MA in the same university with the thesis titled The Maranao Kolintang Music: An Analysis of the Instruments, Musical Organization, Ethnologies, and Historical Documents (1971).

Cadar would be followed in 1976 by Maguindanaon kulintang expert Danongan Kalanduyan as an artist in residence at the University of Washington through a Rockefeller grant. Kalanduyan would spend eight years of residency before completing his MA in Ethnomusicology in 1984. During their stay at the university, Cadar and Kalanduyan taught kulintang music mostly to non-Filipino graduate students in ethnomusicology, establishing as well an ensemble that specialized in Maranaw and Maguindanao tradition. They emphasized teaching the music “in the traditional way, without the use of notation or scores, emphasizing the rudiments of memory and the rigors of repetition, because kulintang is strictly an oral tradition” (Cadar 1996: 133).

Later in the 1980s and upon the completion of their graduate studies, Cadar and Kalanduyan began to shift their focus from teaching non-Filipinos in the academic setting to various community-based Filipino-American performing organizations in different parts of the US. Among these groups were the Kalilang Kulintang Ensemble Inc based in San Francisco, the Tavahika Workshop Inc, later known as the Amauan Workshop Inc. In New York City, the Kulintang Arts, Inc, also in San Francisco, and the World Kulintang Institute and Research Studies in Los Angeles (Cadar 1996: 136-138). Cadar speaks of his decision to pursue the idea of community outreach among Filipino Americans:

My hope was that Filipinos living in America would be receptive, aspiring, and teachable. Part of the challenge was to find such people in the different communities to share this musical heritage with. The ultimate goal seemed to be the integral enrichment of whatever tradition was being passed from one generation to the next. (Cadar 1996: 133)

The article from 1996 quoted above reveals the challenges that Cadar and Kalanduyan faced in their engagement with Filipino American community organizations. Without the structure and rigor that the academic environment afforded them, they often experienced difficulty in bridging differences in artistic orientation and at times even felt exploited. In 1995, Danongan Kalanduyan received the prestigious National Heritage Fellow from the National Endowment for the Arts. After his passing in 2016, his students such as Bernard Ellorin continue to actively perform with various Filipino-American community troupes and university students as well. Usopay Cadar on the other hand maintains an active academic career in teaching and research, having recently completed a film documentary about the Philippine kulintang produced by the National Museum of Ethnology in Japan (Terada 2013). For this project, Cadar partnered with another ethnomusicologist, Yoshitaka Terada, who was a former member of Cadar’s kulintang ensemble at the University of Washington.

Another ethnomusicologist who contributed towards the popularity of kulintang is Filipino-American Ricardo Trimillos who wrote his PhD dissertation entitled Tradition and Repertoire in the Cultivated Music of the Tausug of Sulu, Philippines in 1972. Trimillos established a Philippine music program at the University of Hawaii which included kulintang music. He would maintain a close working relationship with several performing groups within Honolulu’s Filipino population. His greatest contribution perhaps is in the dissemination of knowledge about kulintang and Philippine music in general in the academe as a scholar, and, as a teacher, in the raising of a younger generation of ethnomusicologists who would pursue Philippine music studies. Among them is Bernard Ellorin, a former member of Kalanduyan’s ensemble in California who wrote his MA Thesis entitled Variants of kulintangan performance as a major influence of musical identity among the Sama in Tawitawi, Philippines in 2008.

As mentioned earlier, Bernard Ellorin studied kulintang under Kalanduyan as a member of the Samahan Filipino American Performing Arts and Education Center based in San Diego California (formerly the Samahan Dance Company). With funding from the National Endowment of the Arts, Samahan arranged for Kalanduyan, who was based in San Francisco, to visit twice a month to teach kulintang. Kalanduyan employed a method that he and Cadar developed while teaching at the University of Washington where pieces are cut up into melodic fragments and taught by rote, one fragment at a time until these are committed to memory by the students. At the Samahan, Ellorin was among five students in the training sessions that lasted an hour to 90 minutes. Kalanduyan would play the melodic fragments in the kulintang and these would be repeated by the students using the saronay, a smaller instrument normally used by children in place of the larger kulintang. Kalanduyan would emphasize mastery and rhythmic precision before the students play on the regular kulintang and move on to the other instruments of the ensemble). This is the same method that Kalanduyan used in teaching classes with as many as 25 students when he taught at the San Francisco State University.

The first piece that Kalanduyan would teach beginners was Kaditagaunan, a piece about two sisters setting out to plant sweet potatoes. This was followed by Sinulog a Kamamatuan (Sinulog in the Old Style), a piece that Kalanduyan learned from his mother. These lessons were interspersed with lots of storytelling about his childhood and life in Datu Piang. On several occasions, Kalanduyan organized visits to Mindanao with his students, which in turn encouraged local youth in Datu Piang to value their kulintang tradition even more.

Aga Mayo Butocan

In 1968, Aga Mayo Butocan was in her last year as a BS Education student at Arellano University in Manila when she was told that there was someone searching for a kulintang musician (Liao 2013:20). That someone was Jose Maceda at the UP College of Music who had just established a kulintang program there but was in urgent need of an instructor because the person he previously hired quit the job after a semester. Surprised that there was even such an occupation as a kulintang instructor, Butocan decided to accept the offer to teach at UP, thinking to herself that this would be a temporary arrangement to support herself while waiting for a scholarship application to be approved. She ended up staying in the institution for over 50 years, in the process institutionalizing kulintang instruction in UP, and training hundreds of students in the art of kulintang.

Born in a family of coconut farmers in Simuay Maguindanao, South Cotabato in 1945, Butocan became proficient in kulintang performance at an early age for sheer love of the music (Liao 2013:15-17). She learned by observing the experts perform and trying out the passages she heard at home in the sarunay (miniature kulintang) since her family did not own a full-sized instrument at that time. In her early teen years, she joined her male cousins in all night impromptu music making as well as in public celebrations as often as she could. In short, she learned the way every Maguindanaon kulintang musician did – via oral tradition in informal transmission settings.

While Butocan considered herself as highly competent in performing kulintang music in her hometown and among her people, she was at a loss as to how to proceed with her new position as lecturer in kulintang in the nation’s premier university. After all, there is a vast difference between performing music within a tradition and teaching this music to outsiders, not to mention that these

outsiders were music majors and some even music professors. It was precisely this engagement with cultural outsiders that forced her to look deeper into the practice inscribed by culture in her mind and body and translate this in transmissible terms to her students.

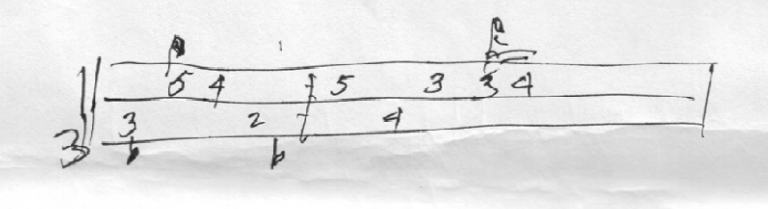

One of the foremost challenges that faced the young kulintang instructor was the rigidity of the academic setting. Butocan taught her students once a week for thirty minutes each session. She realized that when she met the students after a week, they had already forgotten the lesson from the previous session and that they needed to start over again. Her students also kept asking her how to practice on their own during the week – the way they deal with their instrumental majors at the college. It was in her second year of teaching in UP that Butocan decided that a form of transcription would be the best solution to the situation and so she began to devise her own kulintang notation using numbers. The existence of pieces written on paper allowed the students to approach the study of kulintang in the manner they were used to: through literacy.

Figure 1 Early version of kulintang notation by Aga Mayo Butocan (Liao 2013, with permission)

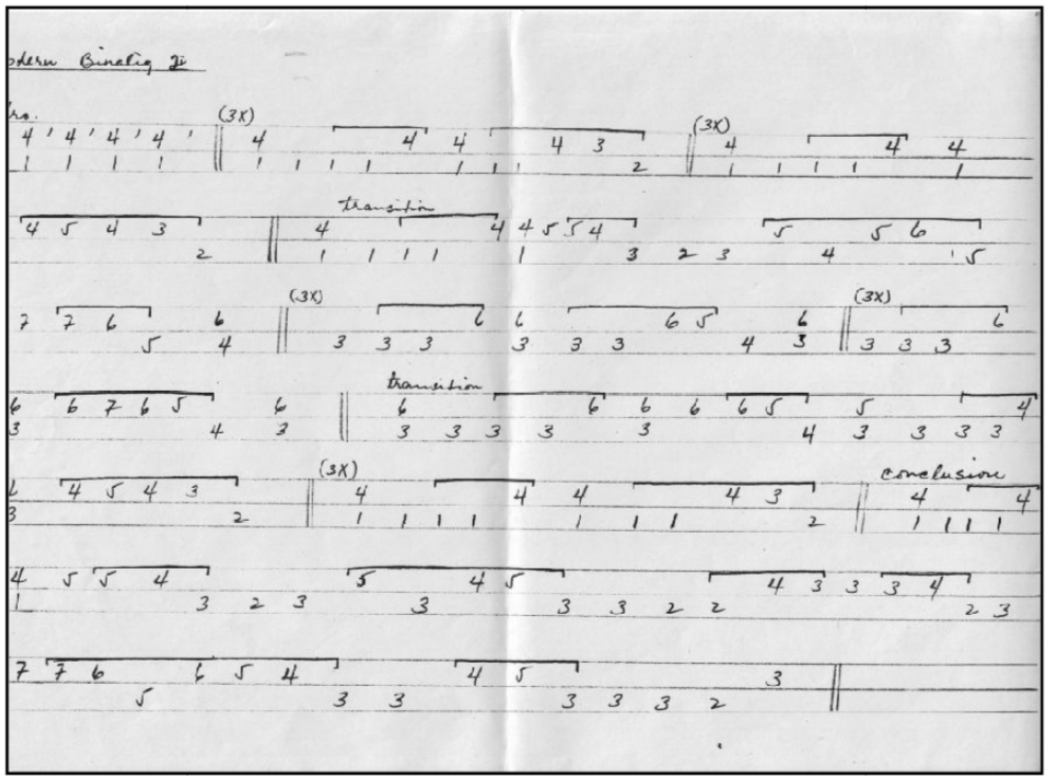

Over the years, and with the help of her colleagues at the college, Butocan would refine her kulintang notation. In particular, two ethnomusicologists returning from their studies abroad would influence her highly: Felicidad Prudente and Kristina Benitez. These same individuals would facilitate the publication of Butocan’s anthology of pieces for kulintang entitled Palabunibunyan: a repertoire of musical pieces for the Maguindanaon kulintangan (Butocan, 1987).

Figure 2 A page of the manuscript prepared by Aga Mayo Butocan for the Palabunibunyan (Liao 2013, with permission).

The publication proved invaluable in providing a textbook, not only for the students in UP but also at the Philippine Women’s University and at the Asian Institute of Liturgy in Music where Butocan also taught. After graduation, her students in turn, used the same book in teaching their own students. Butocan’s Palabunibunyan has become a canon of sorts for the study of kulintang.

It was not however just putting the music on paper that Butocan had to accomplish in her role as kulintang instructor. She needed to examine the way she held the mallets, the manner she hit the gongs, the way she stretched her arms as she played and even the playing posture that she assumes as a performer – matters that nobody taught her but that she imbibed naturally in the traditional oral setting of learning the instrument. She had to find words to describe the ideal sound when students ask her such questions. In short, she needed to verbalize and codify performance techniques. Furthermore, she needed to be able to respond to their queries regarding the music’s function, context and meaning.

While her evolving classroom method, including the use of notation proved to be very efficient in introducing kulintang music to beginning students, Butocan later felt the need to challenge the more advanced students towards the finer nuances of the tradition, in particular, the area of improvisation. She would emphasize to these students that the scores are mere starting points for impromptu composition. Towards her mature years as a teacher and with more command of her teaching space and schedule, she allowed room for flexibility in the classroom such as allowing other students to observe and even participate outside their own time slots. She did this to approximate the social setting of the impromptu sessions she experienced when she was learning the kulintang as a young child.

Today, Butocan has retired from her post at the university but continues to teach there on a part time basis. Her former students, now instructors at the same college, continue the program she guided through the years. She is also now in the process of preparing the manuscript for another anthology, this time including advanced pieces as well as instructions on specific performance techniques.

Conclusion

After more than eight decades of its re-introduction to non-Mindanaon Filipinos in Manila and in the US, kulintang music is thriving in its new environments. Both these streams, Manila and the US, have been facilitated by academics: in Manila by the ethnomusicologist Jose Maceda at the University of the Philippines and in the US East Coast by his colleague, the ethnomusicologist, Robert Garfias at the University of Washington. Maceda and Garfias followed the template set before them by their seniors in the discipline, such as Mantle Hood, of placing research side by side with instruction in the performance of non-Western musics (Hood 1960). The successful implementation of the latter called for the employment of culture bearers – Usopay Cadar and Danongan Kalanduyan in the US and Aga Mayo Butocan in Manila. In the US, Cadar and Kalanduyan began transmission of the tradition in the academic setting but later on, because of a strong demand, began engaging community-based performing groups among the Filipino-American populace. As a result, kulintang groups of various artistic persuasions ranging from the traditional such as Ellorin’s Pakaraguian Ensemble to the experimental like Ron Quesada’s kulintronica which combine kulintang rhythms and electronic dance music (edm) proliferate all over the continent.

Butocan concentrated on teaching college students and in the process institutionalizing kulintang instruction in the academe. She would inspire academe- based composers like the National Artist Ramon Santos to compose kulintang derived music such as his Klntang for piano solo (1982), as well as independent kulintang artist Tusa Montes, a former student of Butocan and currently a lecturer in UP. More importantly, Butocan has taught hundreds of students many of whom ended up as music teachers in elementary and high school, applying her method in their own classrooms.

Finally, the unprecedented shift to the virtual platform propelled by Covid 19 is bridging this divide between North American and Philippine based kulintang enthusiasts. The Tao Foundation for Culture and the Arts headed by ethnomusicologist Grace Nono has organized online courses on Maguindanao music and dance, featuring teachers and facilitators from both hemispheres for Philippine, American and Canadian dancers and musicians. The album Kulintang Kultura: Danongan Kalanduyan and Gong Music of the Philippine Diaspora (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, 2021) co-produced by Theodore S. Gonzalves and Mary Talusan Lacanlale, was also launched and continues to be promoted online. Add to these are the countless independent videos posted in YouTube by kulintang musicians from Mindanao accessible to kulintang aficionados everywhere.

Bibliography

Butocan, Aga Mayo. Palabunibunyan: a repertoire of musical pieces for the Maguindanaon kulintangan. Manila Philippine Women’s University (1987). Cadar, Usopay Hamdag. “The Maranao Kolintang Music and Its Journey in

America”. Asian Music. Vol. 27, No. 2 (Spring - Summer 1996): 131-148. Dioquino, Corazon C. “Musicology in the Philippines” in Acta Musicologica. International Musicological Society Stable. Vol. 54, Fasc. 1/2 (Jan. - Dec.

1982): 124-147.

Hood, Mantle. "The Challenge Of "Bi-Musicality". Ethnomusicology (University

Of Illinois Press) IV, No. 2 (May 1960): 55-59.

Kalanduyan, Danongan. “Magindanaon Kulintang Music: Instruments, Repertoire,

Performance Contexts, and Social Functions”. Asian Music. University of

Texas Press. Vol. 27 No. 2 (Spring-Summer, 1996): 3-18.

Liao, Janine Josephine Arianne. “Rippling Waves: Aga Mayo Butocan and the Transmission of Maguindanao Kulintang”. Undergraduate Thesis,

University of the Philippines, (2013).

Maceda, José. “A Cure of the Sick ‘Bpagipat’ in Dulawan, Cotabato (Philippines)”.

Acta Musicologica, vol. 56, no. 1, (1984): 92–105. Accessed May 21, 2022.

https://doi.org/10.2307/932618.

Terada, Yoshitaka: “Kulintang Music and Filipino Identity in Academia”.

https://www.academia.edu/10750491/Kulintang_music_and_Filipino_ American_Identity.