PULSE VOL.5 NO.1 (August 2024-January 2025)

THE WONDERFUL MISHMASHOF CENTRAL JAVANESEDANCE AND MUSIC

-Alex Dea

Abstract

By 2010, I had been studying Javanese classical music and performing arts fulltime since 1992 (with two years of Ph D research in 1976-77).

I found a plethora of European, Chinese and Muslim costumes, music, objects, and word play in delightful and confounding mixture of elements which seemed arbitrary.

So, I presented my observations as “mishmash”—completely with tongue-in-cheek—with full respect that underlying is something serious.

Here, in 2024, I find that things change but the foundations remain.

I still do not understand how and why the Javanese easily accept, use, and combine elements in their arts. It doesn’t match my way of doing or creating music or art, but I love it, and am certain their creativity is strong and flexible as ever. I hope my observations can give some insight about a different way of doing.

Keyword: Intercultural Creativity, Cultural Appropriation, Southeast Asian Performing Arts, Tradition and Modernity in Arts, Javanese Classical Music

Introduction

I am someone who is always interested in the longitudinal view of things, taking time to observe over long periods of time, to see if things are what I thought, and to see if things have changed, and how that affects my view of things.

In 2010, I wrote about my observations of what appeared to be a ‘mishmash’ of unconnected events, aspects, or cultural elements that seemed to lack cohesion. My thesis was that within this mishmash of Javanese culture lay an underlying sense and intention.

I noted ambiguities present in the interactions of Chinese, Muslim, and European influences. I observed how the Javanese exhibit a versatile and flexible approach to incorporating outside cultural elements, and wondered if it represented exaggerated appropriation for flash and general effect. These elements were everywhere including in the malleability of language.

Now, in 2024, a considerable time since 2010, given the rapid pace of the 21st century—I wish to revisit my findings from that year. [1]

For instance, back in 2010, there was much wordplay with the word ‘De’. I no longer find much of that in 2024, but I observe that Western music has expanded in the Yogyakarta Palace, which now often hosts Yogyakarta Royal Orchestra concerts, recently featuring a Puccini repertoire.

Certainly, there have been many changes in society, economy, and culture in Southeast Asia over the past 15 years. The artists now in their 30s were barely young adults back then. Their views and reflections are different now. They have moved beyond Facebook, racing through Instagram and TikTok.

I invite you to reflect on my observations from 2010. Many of the elements I noted remain active today, reaffirming that the creativity, agility, and inventiveness of Javanese artists are as vibrant as ever, if not more so. I have included images to enhance and celebrate the wonder of this eclectic mishmash.

MY FIRST VIEW

In the early 1970s, the Yogyakarta Palace resumed its dance rehearsals after a hiatus of many years. When I arrived in Yogyakarta (also known as Jogja or Jogjakarta) in 1976, I could only delight in the stories recounted by Bapak Sastrapustaka, a leading abdi dalem (palace courtier), about the wonders of three days and nights of continuous wayang wong (opera/dance) performances.

Not only were there splendid costumes and mythic characters performed by the most renowned and skilled dancers, but what most titillated me was what Bapak Sastrapustaka called the ‘Big Bird.’ He described a dancer dressed as a full-body Garuda, a mythic bird with large eyes, a beak, feathers, and, most impressively, wings that could flap. Atop this ‘Big Bird,’ a warrior dancer would sit and engage in battle.

It was only after the palace performances were revived, and I spent more time there in the 1990s, that I finally saw the ‘Big Bird’—in fact, there were two. It was a magnificent sight. Two warrior women, each perched atop their own large bird, circled one another. They dismounted to continue their battle on foot until the end or until they remounted and exited. I learned that the warrior women were Kelaswara and Andaninggar. Kelaswara was adorned in traditional Javanese attire, topped with a feathered crown.

Figure 1 Two women warriors riding two Big Birds - 1994

The other figure, Andaninggar, was dressed in Chinese costume (Figure 2), which sparked my inquiry into the characters’ identities, their possible region of origin in China, and their place within the context of President Suharto’s New Order (1966–1998), a period when Chinese culture, language, publications, and all associations with China were banned in Indonesia.

Subsequently, I discovered more Chinese dancers. In 1998, after many years, the Bedhaya Sinom was reconstructed. (The Bedhaya is a central element of the Jogja Palace’s dance repertoire, symbolising the king’s mystic power.) In this reconstruction, the ‘Chinese’ woman reappeared, but this time without the large bird, and there were three of them! More recently, in 2011, during another dance reconstruction, the Serimpi [2] Tejo featured two of its four dancers dressed similarly to those in the Bedhaya Sinom.

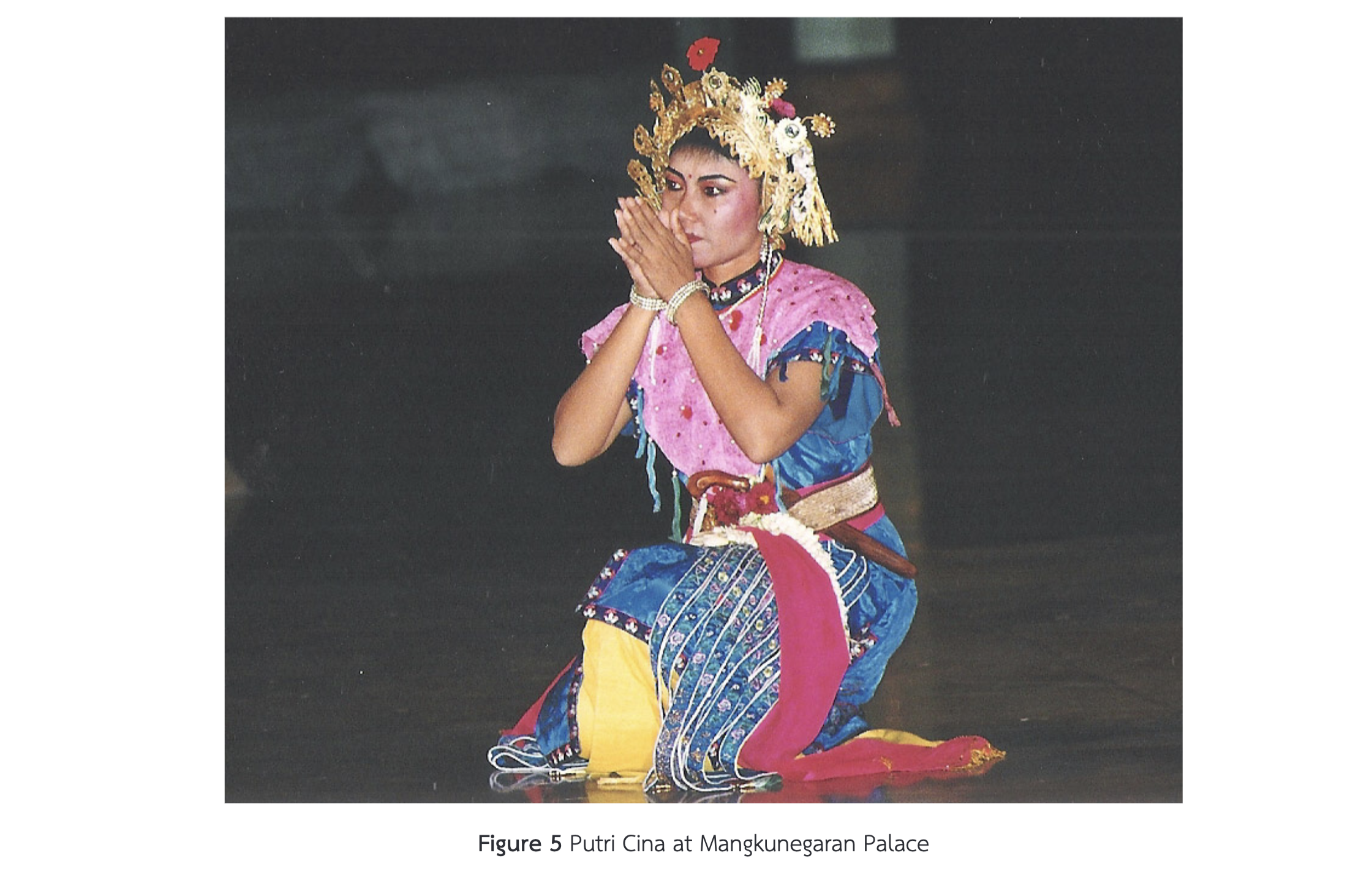

In the other palace city of Surakarta (also known as Solo), at the Mangkunegaran Palace, there are two related dances featuring Chinese characters. In the Serimpi Muncar [3], two of the four dancers are depicted as Chinese. In the Putri Cina, the performance consists of only two dancers: one dressed in Javanese costume and the other in Chinese attire.

It turns out that Serimpi Muncar was brought to this palace from the Jogja Palace when the Prince Mangkunegara VII took as queen, Ratu Timur, a daughter from the Jogja palace. What is intriguing however, is that the costumes of the Chinese dancers in Solo are not exactly the same as those in Jogja.

The Chinese costumes in Jogja are likely from Central Asia, while those in Solo resemble Chinese Han attire (Figure 3-5), as seen often in Indonesian TV series and films from China or Hong Kong. [4] Since the Surakarta dances originate from Jogja, why are the costumes stylistically different? Beyond the question of these costume variations, why are there Chinese characters in the first place? Some dancers in Jogja have told me that these dances are part of the Amir Hamza stories.

CHINESE CHARACTERS IN ARABIC/PERSIAN STORIES

A closer look at the text sung in Serimpi Tejo reveals a reference to the Tartars, suggesting that these Chinese figures might be from the era of Genghis or Kublai Khan. One of my interviewees mentioned that the name Kublai Khan is well-known in general society. Additionally, the famous Chinese emissary Admiral Cheng Ho (a Muslim) is honored at a Chinese temple in Semarang on the Java coast.The Hamza stories (Dastan-e Amir Hamza), which originated in Persia, have seen several translations or adaptations in Indonesia, the most renowned being by the Javanese writer Yosodipuro I. If the Chinese costumes depicted are indeed Central Asian or Mongolian, why, then, do the costumes differ in Surakarta? Moreover, why does the Chinese dancer in Surakarta shuffle her feet and bob her head in a distinctly Chinese manner, while in Jogja, the Chinese dancers’ movements closely resemble those of their Javanese counterparts? Could it be that the depictions in Surakarta are meant to represent non-Islamic Chinese figures?

In the Javanese Hamza story, the Javanese woman warrior always defeats the Chinese one. Does this symbolize Javanese hegemony over the Chinese? But these Chinese characters are Muslim, so why is the Muslim dancer conquered? Some have suggested that, in the late 1800s, when the Dutch had already established political control over Java, the characters —anyone except the Javanese, with the Chinese being acceptable—may have actually represented the Dutch. In the dance, the Javanese triumph over the Dutch, perhaps as a subtle, secretive form of resistance or joke. If there is an identification, it is not that the Chinese are the enemy. Although politically and economically controlled by the European Dutch, the focus is on strengthening the Javanese identity. The authenticity of the Arabic, Persian, or Chinese elements is not as important. The kings will always be Javanese sovereigns, not subjects of the Europeans. And all the while, the Javanese will laugh when serving dinner and entertainment to the Dutch.

It seems that the Chinese costumes exist because of the Hamza stories, and the Hamza stories exist due to their identification with Islam. Then, a twist occurs when the Chinese characters, in the Javanese mind, transform sardonically into the Dutch—the bitterly accepted colonizers. [5]

Does this answer the question of Chinese dancers in the proud cultural element of bedhaya? Throughout the last centuries of the current Central Javanese dynasties in Jogja and Solo, the Javanese royalty, the Dutch, and the Chinese intermixed socially, politically, and in business. As early as the late 1800s, at a royal wedding featuring special performances by the Chinese community in the Mangkunegaran Palace, a parade was led by Chinese performers. Two clues emerge: ‘They marched in the form of a big eagle. Riding [the lead jenggi dancer] was a beautiful lady with light skin’ (Sumarsam, 1995, p. 87). Could it be that the big eagle became the big bird in the Yogyakarta wayang wong? Or perhaps it was the other way around? It’s clear that the ‘beautiful lady’ was Chinese, but what’s intriguing is the mention of her light skin. Light skin is often considered the ideal of beauty by many Javanese. Most Javanese women are dark-skinned and are referred to as ‘manis’ (sweet), but the more desirable light-skinned women (whether Javanese or Chinese) are called ‘kuning’ (yellow). This ties into a gamelan melody called ‘ayu kuning,’ which features the words ‘maya maya,’ referring to the blush of pink on white flower petals—symbolizing a beautiful light-skinned lady with blushed cheeks. This connects to a popular gamelan coquettish dance called Gambiyong Pancerono, [6] sometimes referred to as Pacar Cina (Chinese girlfriend), which might reflect the romantic fantasies of Javanese men toward Chinese women.

EUROPEAN INFLUENCE

Bedhaya Sinom’s Chinese costuming is not the only example of the combining of external elements. The Dutch also play a role in this mix. One of the proud symbols of the Jogjanese palace’s individuality, showing that they are not second to their Surakartan counterparts, is their own distinct style of dance, theatre, and music.

While the dances between these two palaces [7] may appear the same to outsiders—and possibly to the Javanese common citizen as well—there are subtle but distinct differences. The small differences of just a few centimeters in the height and angle of the arms, the precision of turning, and the timing of movements are all very clear to the cognoscenti – perhaps too subtle for the untrained eye. To emphasize Jogja’s uniqueness, the entrances and exits of the Jogja bedhaya [8] are often accompanied by the addition of European military drums (Figure 6), enhancing the gamelan’s already martial tempo and sound. [9] Recently, trumpets have been added (Figure 7), and I’ve been told that in the past, clarinets and violins were also part of the accompaniment.

Figure 6 Recently, Jogja Palace has added more Western drums

Figure 7 Jogja Palace has added many Western instruments

The titles of these pieces are usually preceded by the word “Mars” (also “Marès”), meaning march. While the drums roll militarily, I am sorry to say that the quality of the trumpets is currently below high school level, with many notes out of tune, and tones cracking. It is known that in the early 1920s, the famous German painter Walter Spies, who was also a musician, trained the Javanese courtiers in Western music. In the main yard of the palace, a gazebo still stands, decorated with colored glass depicting guitars, violins, saxophones, and trumpets (Figure 8-10). Apparently, Spies’s students did not carry his lessons into the future. Nevertheless, the grand mars marches onward. Certainly, to listeners, the palace still holds something special, offering a unique experience that endures beyond its history. The sound is militaristic, unusual, and foreign to Java. As Sumarsam (1995, p. 78) notes, ‘One of the consequences of this rivalry was the different ways each royal house integrated European elements.’

Figure 8 Gazebo at the Jogja Palace

Figure 9 Gazebo at the Jogja Palace - details-1

Figure 10 Gazebo at the Jogja Palace - details -2

But is it really that simple? Does the military music signal to the Javanese citizens that their king dominates over the Dutch, or does it serve to appease the Dutch, suggesting that these once-irascible Javanese royals have finally embraced European customs, ways, and subordination? Alternatively, could the Dutch be the unsuspecting targets of a subtle yet unmistakably loud joke?

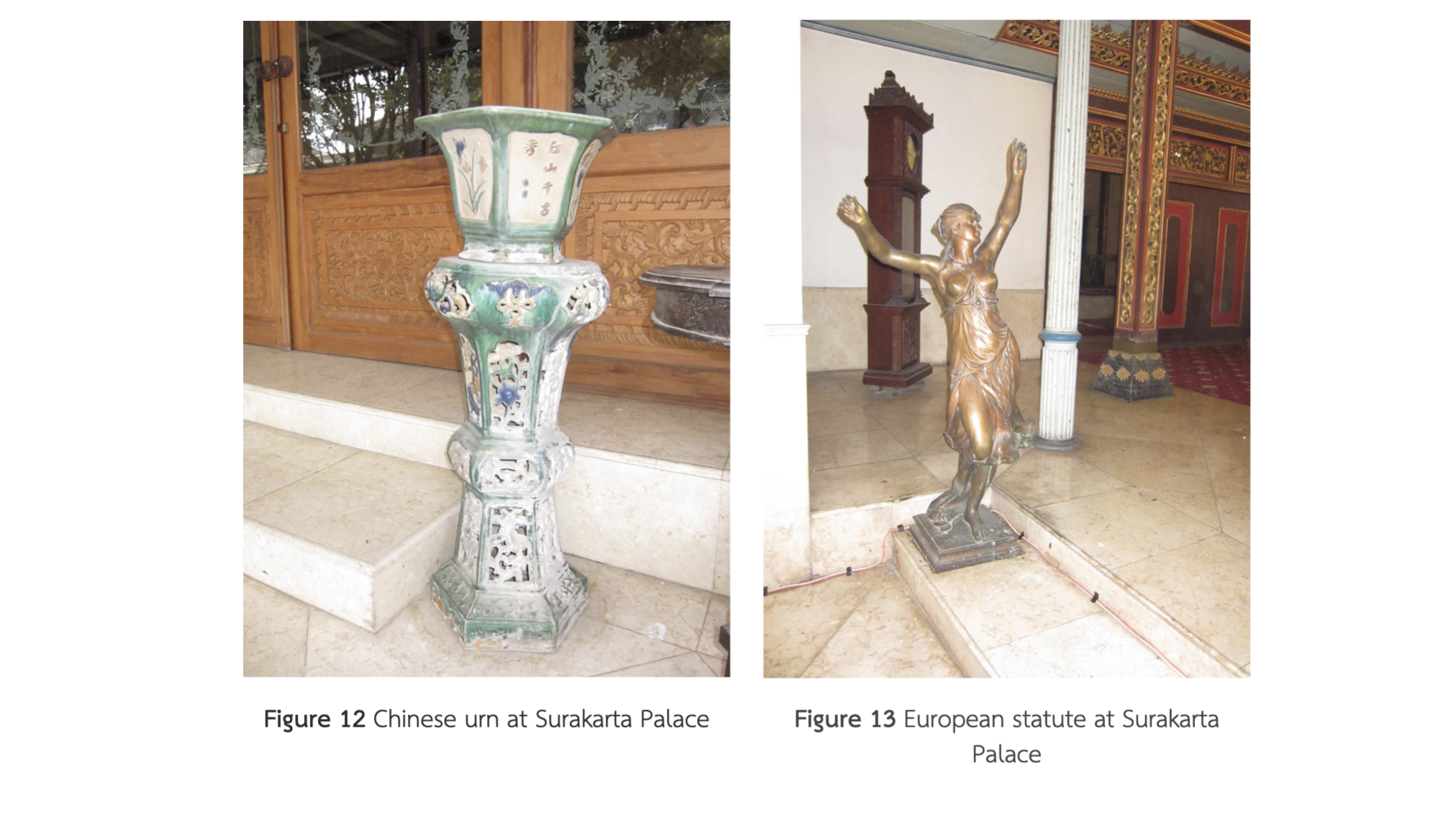

Another example of the competition between the Yogyakarta and Surakarta palaces is the numerous European statues scattered throughout the Surakarta palace (Figure 11-13). Winged cherubs, semi-naked figures, winged women praying, likely Catholic) are depicted in the peripheral areas of the main yard. Some of these figures, wearing diaphanous see-through robes– some topless– are placed not only around the periphery but also directly on the main pendhopo (pavilion), the most sacred and formal public space in the palace. Additionally, similar imagery is found around the adjacent Andrawina guest/dining room, where the glass doors are designed in a European style. Both spaces are resplendent with large crystal chandeliers. Next to these European accoutrements are Chinese ceramic urn-stands here and there, carved stones of Hindu/Buddhist statues, and a Thai hero (possibly a Buddha figure), with his hand in mudra position, placed next to a topless bronze European woman. Once again, much like the Dutch march music, are these statues–symbols of the Javanese king’s ‘own’ identity and power–an ironic appropriation of the colonizer’s symbols? The king (and by connection, the Javanese people) appears as the noble owner of the colonizer’s power. [10]

USE WHATEVER YOU CAN

So far, I have focused on the Chinese costumes and European music, looking at them as something from ‘the past’, allowing for a safe distance to conjecture about someone else’s art. But what about the mishmash apparently in today’s popular culture? I am often pleasantly teased by the combinations of costumes. A few years ago, on TV, there was a show of popular music. I can’t quite remember whether it was Western or Indonesian music, but the dozen or more dancers pranced about in American Indian face makeup, dark bronzed bodies, feather headdresses and colorful loin cloths. Moccasins were de rigueur. The dancers resembled a tribe from the Lone Ranger’s sidekick, Tonto. For an annual New Year bash, the Amanjiwo hotel—a luxury resort in the ‘Aman’ chain, where it’s proudly noted that Lady Di once stayed—hosted several synchronized percussion groups as entertainment for its diners. These men, scantily clad in loincloths, performed dances that seemed to evoke images of ‘primitive’ cultures or perhaps asli (authentic or original), set near the famous Borobudur, the world’s largest Buddhist stupa. Again, more aggressively, American Indian face makeup. Full feather headdresses in evidence. But. It turns out – they say – not American but Dayak, an Indonesian non-Islamic ethnic group from Kalimantan and Borneo, all the while calling their percussion Islamic. Other types of costumed performers strut in parades too. Surely, one of my favorites is marching groups in military formations wearing European military uniforms, with shakos or various Javanese headdresses, but shined up in sequins and colorful satin (Figure 14-15); these young women in alluring makeup.

Figure 14 Women in military costumes-1

Figure 15 Women in military costumes-2

COSTUMING IS BIG

We may expect all kinds of fantasy costumes in kethoprak, a popular folk opera/theatre, full of comedic scenes, romance, and exotic stories suggesting the Middle East or Egypt. The characters wore satin, colorful baggy pants and blazingly sequined sleeveless vests. Each costume was in a different shade—blush blue, creamy green, or hot pink—and topped with oversized, matching turbans. It was, after all, a comedy romance. (Note that turbans are not ordinary headdresses in Java.)”However, I am confused when a family photo of the very serious sunatan, a boy’s coming of age circumcision, shows the two cousins’ ceremonial costumes to be in traditional batik kain, a traditional skirt as may be expected since it is Javanese, but dressed in black velvet jackets with beaded fringe – the same jackets worn by the classical women’s dancers of the Yogyakarta palace. Are the boys wearing women clothing, or are the women wearing something martial, suggesting male power? Most strikingly are the cousins wearing black velvet turbans, not quite as large but the same as the kethoprak. Is this turban pointing to Arabia, taking on the importance and authenticity by identification with the roots of Islam? [11]

My confusion continues over Javanese and Islamic clothing. During a whole-day wedding ceremony, a woman who I know in the wedding party wore modest down-to-ankle clothing in the current Islamic “acceptable” style with a jilbab (head covering) during the morning. However, in the evening, she wore a traditional tight Javanese batik kain (skirt) with the traditional kebaya (a lace skin-tight blouse usually exposing some cleavage). As if to conciliate Java and Islam, her kebaya was unusually high buttoned to the neck. But, below the neck-level collar was a diamond-shaped cut plunging precipitously down an expanse of cleavage.

AN INTERPOLATION WHICH MAY HELP

There is an amazing amount of tantalizing and delicious evidence that in Java, everything and anything can be used. Because Javanese language is highly flexible, ambiguous, and humorous, examining word usage may provide insights into the Chinese-inspired costumes of dancers and the use of European elements with gamelan music.

Recently, the trend has been to add the prefix D, often with an apostrophe, even when the following word does not start with a vowel (similar to usage in French). In Jogja, for instance, there is a D’ Cokro Hotel. However, the use of ‘De’ without the apostrophe remains common. An example is the De Djava restaurant, where the spelling ‘Djava’ evokes a sense of nostalgia for the old way of writing ‘Java.’. And just in case, there is also the De’ Solo restaurant, combining ‘De’ with an apostrophe. One of my favourites is Pasta de Waraku, [12] a restaurant with an Italian and French-inspired name that offers Japanese cuisine—not just noodles, but a variety of dishes.

I wonder if Javanese customers even know if De originates from French. Perhaps it’s enough that ‘De’ conveys a sense of refinement, an air of sophistication tinged with a vague sense of something forgotten—not a nostalgia for their own past,[13] but for a distant time or place, or perhaps even future aspirations, inspired by the current improvements in the Indonesian economy and the emergence of a rising middle class. This reflects acceptance, if not assimilation, of something out of nowhere. Historically, there is no significant French presence in Java. This incorporation of French elements represents a form of modernization—through a French lens.

There are many facets to the flexibility of the Javanese language, starting with the Javanese script itself. Although now rarely used, it still appears on street signs and tourist signage in Java. Unlike other alphabets that follow a linear order, the Javanese script is arranged to tell a story. The story ‘hana caraka, data sawala, padha jayanya, maga bathangan’was once widely known and is now still taught to children during brief lessons as a device to learn the alphabet.

With over 300 years of Dutch rule and the introduction of Latinisation, the spelling of Javanese letters underwent changes. The Dutch were meticulous in distinguishing between the dental and reflexive ‘d’ sounds, using a regular ‘d’ and a ‘d’ with a dot underneath. The same applied to the dental and reflexive ‘t.’ But as the printing technology advanced, rendering those special markings became more challenging. As a result, the dot under the letters was replaced with an ‘h’ added after the letter to indicate the reflexive sounds. For instance, a shadow master is spelled dhalang. Over time, the ‘h’ was often dropped in print, possibly due to publishing simplifications or editorial oversight, resulting in spellings like dalang and bedaya.. However, this has not caused confusion. Native speakers are familiar with the language and intuitively understand which word is intended, correctly pronouncing the reflexive sound even when only the dental form is printed.

Before Indonesian Independence, the Dutch spelled the modern Indonesian ‘u’ as ‘oe,’ so the word ‘dulu’ was written as ‘doeloe.’ There is a restaurant with modern glass decor, offering a menu that features traditional Indonesian and Chinese dishes like noodles, fried rice, and local shaved ice sweets. Alongside these, ‘modern’ options like banana splits, sundaes, and frappuccinos are also available. The name of the restaurant is Roemah Mirota. Mirota is a famous Chinese family whose businesses are bakery, food, clothing, and batik goods. Roemah is the old-fashioned spelling of rumah meaning “house”. So, this is the Mirota House. Fair enough. But why is the spelling in the old Dutch “oe” while the current Indonesian spelling is rumah?

It is to give customers the feeling that this restaurant still touches on the “good old days” (which probably never existed for most Indonesians), ensuring customers that the food is dependable and not too modern. [14] But the prize is on the menu. To ensure that the food is not just any old food, their offerings are titled as Roemi This or Roemi That: Roemi noodles, Roemi fried rice and so on. Roemi is a word made up of Roemah and Mirota, but somehow sounds and seems like a real word.As more foreign words were introduced in the last twenty or so years, words like photocopy were Indonesianized into fotokopi or foto kopi. Kopi means coffee, so perhaps some stores began to spell it foto copy. But a “c” in Indonesian is sounded equivalently to “ch” in English. Therefore, a photocopy could be pronounced a foto chopi. But it is not! People know which way to read and speak.

Probably the height of word flexibility is the government’s own inviting and legitimizing new words which may (or not) be close to or resemble “real” words. Puskesmas is a paste-up of syllables for Pusat Kesehatan Masyarakat, Public Health Center. For words made only of initials, a recent one reminding drivers to only turn left on the green light is called APILL, Alat Peraturan Ikut Lalu Lintas. [15] It could be Alat Polisi Ikut Lalu Lintas. No one, not even taxi drivers who roam the roads everywhere and anytime, know exactly the acronym’s derivation or meaning. But everyone knows that they better beware not to turn left on a red light. [16] When asked where these new words come from, a friend said orang pintar, smart people. The ability to make up words is respected.

Public word HUT, Hari Ulang Tahun (day of repeated year, meaning birthday) has been replaced with Ultah, Ulang Tahun. A Javanese friend notices wryly that the replacement may be because HUT is too short, suggesting that someone may be short-lived whereas Ultah has a longer spelling, therefore suggesting something (more) eternal.

Well-known but probably not government words are WIL and PIL, Wanita Idaman Lain, and Pria Idaman Lain: Woman Desirable Another and Man Desirable Another, meaning the lover woman or man in an extra-marital affair. Usually, WIL and PIL are mentioned jokingly or sardonically.

Smart and humor go together or in parallel with the general society’s enjoyment of made-up words. “Nasgithel” is tea which is especially delicious: paNas, leGi, kenThel meaning hot, sweet, thick. Not enough to have just one word, there is also a resequenced Ginasthel, leGi, paNas, kenThel, and an extended Ginaspethel meaning leGi, paNas, sePet, kenThel meaning sweet, hot, dryly tart, and thick. These words are usually said with a smiling knowing wink.

“Èmbèr” is a pail or bucket, but everyone was going around saying everything “èmbèr”, meaning Sure! Of Course! What Else? Coming from “memang benar” meaning “certainly correct” or “memang begitu” meaning “surely like that”. Always said with a smile and a laugh.

Besides this wonderful mixture of word creation, some of which are readily understood, I wonder that the same initial-word can have two different derivations and meanings. BBM generally means petrol or gasoline. But in a recent public scandal where someone was accused or proved of guilt, BBM means the text messages sent via a Blackberry. [17]

The love of pun, mlèsèd (slipping), and jokes helps people lighten up their travails. After the eruption of Merapi Volcano near Jogja where hundreds of people died, most of those whose homes were destroyed moved into government-built refugee quickly-built wooden houses. Although the government clearly stated that there would be no aid for those living within the danger perimeter, one village nearest to the top of the Merapi chose to return and rebuild their homes. These resilient hardy people are enterprising. Because local tourists came in busloads to see the disaster, this village created a gate and started an entrance fee. Inside, a rough stage was set for local performances. A makeshift restaurant sold food. The menu included Nasi Goreng Vulkanik (Volcanic Fried Rice), Nasi Goreng Kendit (Fried Rice of Persons Who Escape Danger), and Soto Awan Panas (White Volcanic Cloud Chicken Soup). While they are joking about their plight, they are also either thumbing their noses at – or giving respect – to the universe. Just for an extra hit, they added to the menu list, Tante and Pakté which are normal words meaning Auntie and Older Uncle. What they really mean is a plèsèdan (a slip) for tanpa telor (without egg in the noodle) or pakai telor (with egg).

Word-play in Java shows agility and easy acceptance of something outside of the norm. This word-play is one example that outright and outrageous hybridity is pervasive and natural. Note that it is not the blame nor praise for any one culture or time either. [18] It just happens.

SO, WHAT ABOUT THIS JAVANESE MISHMASH?

A brief glance at long human history reveals a period in the late 19th and early 20th centuries marked by heightened Orientalism and an interest in non-European dance in the West. For example, in France, there were practitioners of Japanese, Javanese, Indian, Cambodian, Latin American, American Indian, African and other dances. Notable dancers included Uday Shankar, Ram Gopal, and La Argentina (who inspired Ohno Kazuo the Japanese Butoh pioneer).

However, this fascination with the exotic was not one-sided. Many western dancers also performed non-western styles. Matahari (née Margaretha Zelle) is the most well-known, but there were many others including Ragini Devi, born Esther Sherman in Michigan USA, and Nadja, born Beatrice Wanger in California. One of the most well-known today is Ruth St. Denis (née Ruth Dennis). She created her first non-western dance inspired by an Egyptian goddess featured in a cigarette advertisement.

Is there a difference between the incorporation of non-Javanese Chinese and European elements into the sacred bedhaya repertoire and Ruth St. Denis’s later Indian dance and costuming? St. Denis was not trying to reproduce Indian dance but was working with its inspiration and essence, using external elements to access something deeper–her own mystical muse (Rossen, 2010). Are Javanese choreographers and dancers, past or present, approaching this differently? [19] I have been discussing classical Javanese dance, but my fascination with this wonderful mishmash also extends to contemporary and modern choreographers. It all forms part of the whole. After all, in Central Java, nearly all dancers who dare to innovate with something new and contemporary are primarily trained in classical dance.

As the evidence of St. Denis’ success in that there was a generation (or more) of dancers who sprung from her work into what became “modern dance”, I am supremely confident in speculating that the Javanese future with whatever generated non-Javanese elements they use will (eventually) produce something interesting and enduring, and most importantly, they will have fun – sometimes with a hidden relaxed humor. Although the palaces’ older bedhaya have already proved themselves, current experimental dance in Jogja and Solo is still struggling. However, while not all of the recent or contemporary experimental dances hold interest, there is sufficient and positive evidence that such as the Bedhaya Hagoromo [20] (which integrates with the well-known Japanese noh piece) and Bedhaya Layar Cheng Ho [21] (the story of the mentioned Chinese Muslim emissary) which mixes with high levels of non-Javanese elements are on the right track. [22]

Perhaps it is not so important that most Javanese dancers do not know some detail as simple as that Jayarengga, the main character in the Hamza story, might actually be the Prophet Muhammad’s uncle. Likewise, it may not be important that one of the best dance drummers does not know that Pacar Cina is another name for the Pancerono dance (Hartono, personal communication 2011). The Javanese choreographers and composers whom I know have a different attitude and approach. Fidelity to accurate historical facts or truth in precise details is not of paramount importance. [23] The evidence is that their creations which incorporated Chinese costume or European march music continue to hold interest in the repertoire and style. After many years and performances, this cannot be considered superficial elements although it may have started that way.

Where the march music of the sacred bedhaya may or not have been a paean to the Dutch masters, the easy assimilation of non-Javanese music also suggests flexibility and acceptance of something new or different. The Westminster bells in the classical-styled Ladrang Westminster (or also spelled Westmester) melody is clearly understood by all – sometimes with a solo cadenza of the ticking of a clock with a cuckoo’s warble. This humorous interjection sits well with the bell melody which itself could be a tickle of a joke. Whether it started as a joke when a European ballroom dance melody was incorporated into the repertoire of the sacred sekatèn gamelan celebrating Muhammad the Prophet’s birthday, certainly the musicians now always have a chortle of pleasure. I do not think they are laughing at Islam or Muhammad’s birthday. They are just a normally good-humored lot.What is clear is that the Javanese artists are resilient, and full of creativity, agility, and invention. Whether something is original or borrowed is not of primary importance to their creations. Whatever is used is subsumed by what they feel in their heart. It is perasaan: feeling and intuition. The creative impulse and emphasis is not on the Apollonian, but on the Dionysian. The Javanese artistic temperament and history proves their independent originality.

Along the way, the use of details such as colored ostrich feathers fitted into the classical serimpi headdress which might show off that the king has something which no one has – possibly given as tribute (or advertised at least to the Javanese populace) by the Dutch – or the use of pistols instead of the Javanese kris (dagger) in the bedhaya or serimpi showing power and possibly reminding the Dutch that Java had high-tech weaponry too, may symbolize or represent to the Javanese public the king’s identity of his sovereignty from the Dutch. At the same time, there may be a secret joke that the Dutch had better be careful that the pistols are not pointed towards them. The Javanese artistic temperament and history shows that they are no one’s colonized. They will be no one’s second fiddle.

[1] This revised article was originally presented at Asia Pacific International Dance, APIDC 2011 Conference, Kuala Lumpur, September 2011,

and subsequently published as “Dancing Mosaic: Issues on Dance Hybridity” Cultural Centre University of Malaya & National Department for

Culture and Arts, Ministry of Information Communication and Culture, Malaysia

[2] Serimpi is a royal dance genre closely related to bedhaya but with only four dancers.

[3] In a photo annotated by the famous batik designer and documenter Iwan Tirtaamidjaya, what appears to be a Serimpi Muncar performance

in Jogja, danced by a Jogjanese dancer, is labeled ‘Putri Cina’ (young Chinese girl or lady).

[4] A Chinese ethnomusicologist suggests that the Mangkunegaran costumes resemble those worn by Southwestern Chinese ethnic groups, such as the Miao and Zhuang. On the other hand, the headdresses of the Yogyakarta dancers appear to be influenced by styles from west of China, possibly Persia.

[5] The independence of gamelan and European music can also be seen as a reflection of the general colonial experience. This general pattern concerns the nature of the relationship between the colonizer and the colonized: the ruled must recognize the ruler as both ally and enemy.” (Sumarsam, 1995, p. 75)

[6] Pancerono in Javanese language is pancer and ana (spelled ono). Pancer is a musical technique where an ostinato note is alternated between the composition’s basic melody. “Ana” or ono means “to be”. Therefore, since there are several variations of Gambirsawit compo-sitions, this Gambirsawit Pancerono composition is the one with ostinato alternating notes.

[7] Actually there are four palaces. There is one high and one lower palace in each of Surakarta and Yogyakarta.

[8] Surakarta also considers bedhaya as a prime power and mystical accoutrement.

[9] The Surakarta bedhaya entrances and exits are by a much more refined, ethereal texture of small gamelan ensemble and male chorus

[10] In the Surakarta palace, on top of the main big doors entering the palace proper, is a carving symbolizing the palace. In the centerpiece is the well-known kingdom’s emblem with sun, moon, and star. Radiating from that are weaponry including cutlasses, swords, and kris: three of Javanese and three of European-styled. There are two cannon, one on each side. Although cannon may have come from Europe, the Javanese may have manufactured their own. Notably, there are musical instruments: the European military drum balanced by a Javanese gamelan instrument (too small to be a gong ageng – the big gong, but either a kempul or bonang.) Atop the whole array is a crown – seem - ingly European! Does this carving mean that the Javanese kings encompass the European/Dutch power? Does the crown mean that even though it is European, the Javanese is wearing it as their own; the king showing it that the enemy’s head is “owned”? Or is the balance of European symbols an obeisance (seemingly) to the colonizer?

[11] In the museum in the Yogyakarta palace, there is a photo of king HB-9 during his circumcision ceremony wearing the same type of turban.

[12] Waraku is a Japanese word meaning peace and harmony. This restaurant chain Waraku Holdings Pte Ltd is based in Singapore although there is Waraku Japan Co. Ltd on the organization chart. This company’s vision of “...bringing authentic Japanese cuisine from Kyoto prefec - ture in Japan ...” doesn’t necessarily mean that the company comes from Kyoto!

[13] Such as the oft used old spelling of Tempo Doeloe, and not the current Dulu, meaning Times Ago.

[14] Many of my older Javanese friends are afraid to try new foods.

[15] Lalu Lintas means traffic. Alat means tool. Peraturan means rules. Polisi means police.

[16] In Jogja (and most of Indonesia), drivers are notorious for driving wherever and whenever they wish

[17] Bakar is burning. Bahan is something. Minyak is oil. For the other BBM: BB is Blackberry. M is message (English word!)

[18] James Clifford in “Routes” notes “My approach to museums – and to all sites of cultural performance and display – questions those visions of global, transnational, or postmodern culture which assume a singular and homogenizing process. “Question” here suggests a genuine uncertainty, an ambiguity sustained.”

[19] For whatever reason there may be for incorporating the “other’s” elements, it is interesting to note a difference. Ruth St. Denis came to Indian dance movement, costuming, and concepts from the outside while the Javanese bedhaya comes from within, drawing on external influences. While St. Denis was seeking her own center of dance, the bedhaya was already rooted in the center.

[20] By the well-known and popular cross-gender dancer Didik Nini Thowok in Yogyakarta

[21] By Bambang Besur Suryono, one of the top classical dancers (and a primary dancer of the modern choreographer Sardono) in Surakarta.

[22] Recently, on November 2, 2024, after its premiere 24 years ago, Bedhaya Hagoromo was reperformed to great applause and appreciation in Jakarta, to open the Indonesian Dance Festival’s 32nd year.

[23] In the Surakarta palace and outside, a Manipuri dance is performed. A different paper is needed to discern how close (other than the name and some vague borrowing) this dance relates to Manipuri, one of India’s recognized classical dances from the state of Manipur

References

Banes, S. (1977, 1978, 1979,1987). Terpsichore in sneakers. Middletown, Ct: Wesleyan University Press.

Boon, J. A. (1991). Verging on extra-vagance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Clifford, J. (1997). Routes:Travel and translation in the late twentieth century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

De Mille, A. (1963). The Book of the dance. New York: Golden Press. Décoret-Ahiha, A (2004). Les danses exotiques en France 1880-1940. Pantin: Centre National de la Danse.

Dirks, N. B. (Ed.). (1998). In near ruins: Cultural theory at the end of the century. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Duncan, I. (1968). The autobiography of Isadora Duncan: Originally published as “My Life”. New York: Award Books.

Errington, S. (1998). The death of authentic primitive art: And other tales of progress. Berkeley: UC Press.

Jameson, F., & Miyoshi, M. (Eds.). (1998). The cultures of globalization. Durham: Duke University Press.

Martin, J. (1946). The dance: The story of the dance told in pictures and text.New York: Tudor Publishing Company.

Mloyodidodo, S. (1977). Gending-Gending Jawa gaya Surakarta, Jilid II. Surakarta: Akademi Seni Karawitan

Rossen, R. (2010). Ruth St. Denis & Ted Shawn: Modern dance pioneers. Dance Teacher. Retrieved from http://www.dance-teacher.com/content/ruth-st-denis-ted-shawn

Rustopo. (2006). Menjadi Jawa: Orang-orang Cina dan kebudayaan Jawa di Surakarta, 1895-1998. [No publisher Indicated]. Surakarta, Indonesia.

Shelton, S. (1990). Ruth St. Denis: A biography of the divine dancer (AmericanStudies Ser., No. 21). University of Texas.

Sumarsam. (1995). Gamelan: Cultural interaction and musical development in Central Java. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.130