PULSE VOL.3 (January 2023)

Dialogue between a voice and two bamboo mallets - an interview with Omkar Havaldar

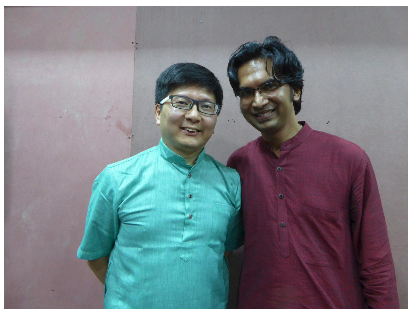

- Kimho Ip

In 2019 I was invited to India to join the Saath-Saath [1] intercultural collaboration, a 3-year project curated and implemented by Prof. Tejaswini Niranjana in connection with Hong Kong where she worked and Bangalore in India where her hometown was.

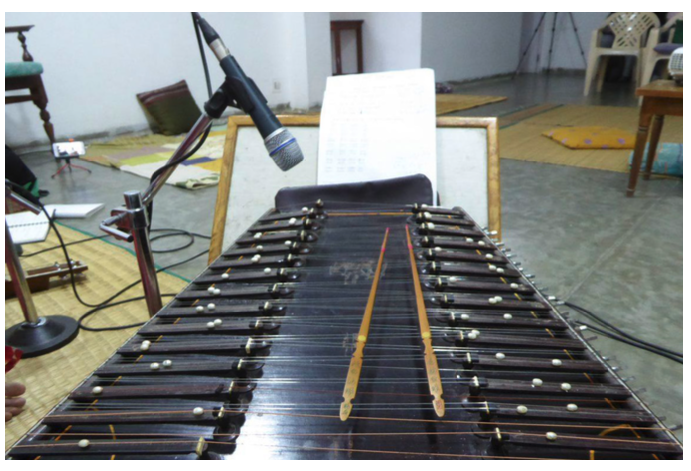

The collaborations between musicians and scholars in the Saath-Saath project aimed to generate a strong interest in thinking through questions of cultural practice in China and India [2]. One of the key musical explorations during my 10-day residency in Bangalore was to apply instrumental techniques of my yangqin [3] to the santoor, and learn to improvise with Indian singers in the Hindustani classical musical tradition. The outcome of my residency included performances in Bangalore and Mumbai, and a 2-CD album named Re/Semblance: Saath-Saath, that was produced in Hong Kong during the pandemic in 2021.

This paper complements another published article of mine titled, A Hongkonger in Bangalore - Travelling with Two Bamboo Mallets, in which I wrote about the concept of home viewed through the performance practices of musicians, and how a musical work can be a representation of the trace of a movement, of a journey. In 2011 and 2014, I was a Research Fellow in Performance Studies at the International Research Centre Interweaving Performance Culture, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany. My residence at the research centre in Berlin had a significant impact on my approach on intercultural dialogues from the view of a practicing musician, and provided the theoretical framework on interweaving performances and cultures. As an extension to that article published by the research centre in Germany, this paper is the record of an interview in 2019 between me and one of the singers in the Saath-Saath project, Omkar Havaldar. Omkar is a Hindustani classical vocalist based in Bangalore and trained in the Kirana, Jaipur-Atrauli, and Agra gharanas [4]. The interview summarises our exchange of ideas on musical traditions across cultures through our collaboration. It is also a dialogue exploring the differences in musical practices between Omkar as a vocalist and myself as an instrumentalist.

Traditional method of teaching Indian classical music - from vocal to instrumental

Kimho Ip (KH): Its the 29th of June 2019, today. Omkar and Kimho are sitting together in the hotel in Bangalore5. I would like to ask Omkar a couple of questions, so that he can also share with us the experience both during the last week in Bangalore, and in relation to some of our experiences when we first met each other in Hong Kong last November.

Omkar, I have been learning Indian classical music from you. You teach me using traditional Indian classical method [6], that is to sing the raga together, and later we practice that together. We do not just learn that raga together, we know the raga eventually. Can you tell us more about this method of teaching?

Omkar Havaldar (OH): it is always a pleasure talking to you, Kimho! Going back to our experiences in Hong Kong in November 2018, and in Bangalore in June 2019, the way we have interacted and the way we have learned together is essentially the traditional method of teaching Indian classical music. Let me explain what that is. Generally, Indian classical music is vocal-based. Every instrument would aim to approximate the human voice as closely as possible. So, the vocalist is given the highest importance in Indian classical music. These are not just my words, but generally this is considered to be the toughest aspect in Indian classical music. This would be the same if I am teaching a pipa player, a yangqin player or a cello player like yourself. You will be surprised that a composition like Tore Nagariya (learned on the yangqin), can play also be on the cello. How are you able to do that? First you have internalized the raga vocally. So you now know how to sing that. Since you are an extremely capable artist both on the yangqin, as well as on the cello, you will be able to translate all the vocal expressions onto your musical instruments.

This is the traditional Indian way of teaching music. Having said that you have tremendous expertise in both instruments that I have nothing to do with. As you have seen, we focused on any techniques of playing the instruments. Instead, we only dealt with the techniques of learning the raga, learning the composition, and internalizing it by singing. It is only after internalizing the raga, that you translate the techniques onto the instruments. That’s the methodology we employed to interact. I use the word internalize because as you notice that you are playing the composition by looking at what we have written down on the paper as notation, for example the taan. But in the performance you did not look at the paper. You started to play the music creatively. That is the method! That is what Indian classical musicians do [7]. We train to become creative. Internalizing the raga is very important because we would know as we internalize it, we won’t forget it. We simply remember it through this internalizing. That’s the importance of internalizing, knowing and remembering.

In Indian classical music, what do we mean by knowing? For instance, we may or may not remember the name of a schoolmate or classmate after several years of passing out from school, but the chance of forgetting our parents’ names are minimal or next to nil since we ‘know’ out parents. We never forget our language because we ‘know’ our language. We do not need to remember our language. Remembering usually takes place at the surface. Knowing takes place at a deeper level. That is the difference!

KH: In other words when I learn the raga with you, we have to internalize it until we know the raga.

OM: Yes. You can say so. If I have to learn to have a conversation in Cantonese, in the span of one week, I could probably memorize ten questions and answers, which I may later forget. But if I study the language and ‘know’ it thoroughly, I will be able to create any sentence and express myself in a way that I choose. That’s the method of knowing the raga: it’s not just Tore Nagariya, that you know how to play on your instrument, but you can also create your own tune in raga Bhairav, which forms the basis of the composition, Tore Nagariya This is the ultimate aim of the process of internalizing. So, one fine day, if we have a beautiful session on raga Bhairav, you will be able to play ten other compositions of your own, since you would have internalized it. You have the liberty to create your own compositions, once you have learnt, known, and internalized the notes of a particular raga. In a way, we are trained to be creative [8]. I will come to that part later.

Practicing exercises on instrument

KH: As you have mentioned, I have learned the raga Bhairav from you, last November using traditional Indian method. I have to internalize the notes and apply some of the techniques on playing the yangqin. For that, you wrote some exercises on a sheet of paper for me to practice. Can you tell us more about these practices?

OM: These are basically exercises which will allow us to make different combinations in a raga. For example, this is the root and the scale of the raga Bhairav:

Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Ta [9] Ni Sa - Ni Ta Pa Ma Ga Re Sa

What are the possible exercises that can come about here?

For example if we sing the scale and reduce one note at a time: Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Ta Ni - Ta Pa Ma Ga Re Sa...

(see fig. 1)

Except for the first one, everything is in derivation.

By doing these exercises we understand the importance of the root and the derivations. When you understand how to derive from the root, then it becomes infinite because you can keep deriving. These exercises will lead us to derive and explore the raga in a much broader way.

The second exercise: (see fig. 2) GRGR GGRS

If you drop the first GR, that is again a derivative. If you drop both GR, that is a third derivative. Deriving out of each equation is an endless process, hence every musician is trained to be creative. These exercises are part of the creativity.

Creativity here again should be understood as the creative process involved in improvisation. In my other article on the freedom of improvisation, I explained how improvisation is never entirely free. The musical practice on yangqin or on santoor has provided the framework for improvisation to take place. To apply these practicing exercises on yangqin, this technique can be described, as “a transcultural manipulation, to find ways of improvisation that may reconcile my practice and the Indian classical tradition [10]”

OM: Kimho, I now request you to come up with any combination, just take a pen and paper and write down any combination in the raga Bhairav scale. Let me tell you how we can derive.

(KH wrote a downward scale): Sa Ni Pa, Ni Pa Ma, Pa Ga Re Sa

OM: If we leave the first note: Ni Pa, Ni Pa Ma, Pa Ga Re Sa If we leave the second note: Sa Pa, Ni Pa Ma, Pa Ga Re Sa Leaving the third note: Sa Ni, Ni Pa Ma, Pa Ga Re Sa

And: Sa Ni Pa, Pa Ma, Pa Ga Re Sa

KH: So, from a random combination of scale I have written down, you can take away one of the notes and keep making new combinations.

OM: Yes. The possibilities are endless.

KH: You use the word derivation.

OM: Derivation from whatever combinations we think of.

Here are more examples of derivatives (see fig.3)

These are basic examples how we can endlessly sing and derive from the same combination.

If we double one of the notes:

Sa Sa Ni Pa or

Sa Ni Ni Pa or

Sa Ni Pa Pa

And then,

Ni Ni Pa Ma Ni Pa Pa Ma Ni Pa Ma Ma

Pa Pa Ga Re Sa

Pa Ga Ga Re Sa Pa Ga Re Re Sa

Pa Ga Re Re Sa Sa

and,

Sa Sa Sa Ni Ni Pa, Ni Ni Ni Pa Pa Ma, Pa Pa Pa Ga Ga Re Sa

Increasing the number of repeats, to skip a particular note, to sing a particular note twice, these are derivations. These exercises are important.

Going further, taking the same exercises. In your Bangalore visit, you were able to do the same exercises on raga Bhibas. In a way, these exercises can be applied universally, and you could start applying them on different ragas. If we learn and master one particular exercise in one raga, if we are strong and perfect with the exercise, we can apply that to other ragas too.

For example, for the raga Bhairav there is this exercise:

Sa Re Ga, Re Ga Ma, Ga Ma Pa, Ma Pa Ta, Pa Ta Ni, Ta Ni Sa

If we have to put the same thing in raga Bhibas, where there is no fourth note and seventh note, it will become:

Sa Re Ga, Re Ga Pa, Ga Pa Ta, Pa Ta Sa

From raga Bhairav, we are translating the one-two-three pattern to raga Bhibas.

On transferring skills from yangqin to santoor

In another article I wrote about the experience of my first encounter of the santoor:

“Santoor and yangqin: similar yet really different; familiar faces yet really strangers. Each step ahead encountering unexpected response, my past practice on yangqin represents a point of reference, a point of departure, a sense of home. What I am familiar with is to a certain extent the common technique of movements with a pair of mallets on both instruments, using both hands with equal dexterity. Yet further exploration on the santoor produces unfamiliar sounds and unexpected sequence of notes. Locating musical notes of a scale, it sometimes corresponds to my expectation but occasionally contradicts. My apparent acquaintance with the technique of movements is responded by sounds that are unfamiliar, creating a strange, foreign feel to my hands, to my ears and to my eyes.11”

Travelling in this familiar yet foreign terrain of the santoor, I described it as a journey away from home which is represented by the musical practice associated with the yangqin.

KH: My next question will be based on the last week we spent together in Bangalore. This time I have performed with you the same raga Bhairav, that I learned from you in Hong Kong. In Bangalore, I challenged myself by trying to play it on the Indian santoor, which is the first time I have ever played this instrument. You said you were so amazed by how, like a miracle, I could do it within four days. Can you share your thoughts about the challenge, and how well you think I was able to try it on the Indian santoor?

OM: I definitely feel that it is nothing short of a miracle of how you could actually play the Indian santoor. In fact, in the discussion we had with Professor Niranjana at her place while we were rehearsing, you made it very sharp in our conversation, you said, “you cannot give a foreign instrument to somebody and ask them to improvise.” That got me thinking. And to much of your dislike and disagreement, Kimho, you disproved yourself (Both laugh). You did improvise on that instrument. And I think you are able to do it because the yangqin is a much more complex instrument than the santoor. On the santoor, the notes Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Ta Ni Sa could be played by following a vertical movement, but on the yangqin it is a complex zigzag movement. That is what I have learned from you, right?

KH: yes, you are right.

OM: Having that map in your mind, and coming of that map and seeking some other map to play the ascending and descending notes, I think, is indeed remarkable of you. I will tell you what I found even more remarkable was that you were able to play the raga Bhibas on the santoor which was tuned to play the raga Bhairav. This is simply fantastic because you managed to skip the fourth and the seventh notes that do not form part of the raga Bhibas. First of all, it is a new territory, a new maze for you. And you were still able to recognize that you are not supposed to play the fourth and seventh notes. When descending, you manage to play a different set of strings. I think that is remarkable and I could not have imagined anybody could achieve this within a span of four or five days.

If we talk about the show, you already demonstrated the kind of understanding and mastery on your instrument. This is the inherent philosophy of all Indian classical music. If you are able to understand the methodology of developing one raga in depth, you have pretty much mastered the art of developing any raga. Here, nobody has taught you the way to play the santoor. But you are able to play it. Why? Because you have mastered the art of playing the yangqin. And what you have to understand here, are the do’s and don’ts on particular strings. You have to know that. It is like learning to drive a car. If you have learned how to drive in Hong Kong, does it mean when you go to Shanghai you have to learn to drive again? No. There you have to know which route to take. That’s all. Similarly, the santoor became a different place for you. You already knew how to drive, that is playing the yangqin. That is why you were able to remarkably achieve that kind of perfection. You are amazing!

KH: Thank you for your praise. I am curious also, do you notice any difference the way I play compared to traditional Indian santoor player? Did I break some rules or do something wrong?

OM: We have to keep in mind that you are not a player of the santoor. Even the way how the santoor is held is very different. Santoor is generally kept on your thighs. You fold your feet during the performance.

KH: Because of this way of holding the instrument, that changes the way how people play it?

OM: Yes. Your hands are holding slightly differently. It’s also a different speed of playing. Hence, the clarity is a bit different. Your comfort of interacting with the instrument is different. All those things matter. And coming onto the tuning of the instrument, we have tuned also it in a different way.

KH: How would you compare the experience when we did the same raga on yangqin, and to the one we played together on the Indian santoor?

OM: I think it is a very funny answer. In Hong Kong, you were new to the raga Bhairav. Here in India you are new to the santoor. But you are already familiar with the raga Bhairav!

KH: That’s true.

OM: So when I come to Hong Kong this November, you would have mastered playing the raga Bhairav. Having said that, in Hong Kong you are on your own instrument. You are more comfortable on that compared to the santoor. There is absolutely nothing I would take away from your playing of the raga Bhairav. Since you have spent time with the raga Bhairav in the last couple of months, I felt that you are already very comfortable with it. I am looking forward to our next jamming in the coming November [12]. You will be familiar with both, the raga Bhairav and the yangqin!

KH: Although I am starting to be curious, now I am familiar with playing the raga Bhairav on the Indian santoor, and when I switch back to the yangqin, I may feel strange! [13]

OM: Oh! We will see.

On teaching musicians from other cultures to play Indian classical music

KH: Coming to the last part of our discussion, we are planning for further collaborations. What do you think we can try to attempt and explore together?

OM: Our collaboration will be a great inspiration for non-Indian students of music and musicians to learn Indian classical music. We are fully connected and really understand each other. Together we can convey this message in the future collaborations. Many people are generally fascinated by Indian classical music all over the world. If they see us working together, we can convey to them that Indian classical music can be learned with a given preparation of the instruments we play, and the teaching pedagogy I conveyed. They both go hand in hand. Indian classical music can be performed on a very high level.

KH: You said that Indian classical music can be performed on a higher level. Are you also happy to see some instrument players who are not Indian classical, but play like Indian classical musicians?

OM: I would love it. That’s just fascinating for me. Like you play Indian classical music on the yangqin. I did not even know how to pronounce the name of this instrument before I met you. And raga Bhairav is one of the most ancient ragas in our culture. Any Indian would really love it.

KH: That will be the same for western instruments. They can learn the way of Indian classical music.

OM: Absolutely. The only difference is between the instruments. For example on the pipa you can play the glide, which is a very integral part of Indian Classical music. On the yangqin, it is not naturally done. You have to apply non-conventional methods to play the glide.

KH: In short, what do you think is the essential thing you want to teach people who want to know more about Indian classical music tradition?

OM: In the Indian classical music tradition, we are trained to be creative. What is the methodology of being creative? In western music there are three aspects for performance: one is the composer, second, the conductor, and third, it is the performer. But in Indian classical music, you are all three-in-one. You are your own composer because you can compose your own songs. You are your own conductor because you want to know in what direction the song has to go. And you are performing yourself. When this happens, musicians have more freedom and creativity. This is what Indian classical music gives us. Everywhere I want musicians to enjoy absolute creative freedom which Indian classical music has given me. That’s what I want to convey.

[1] Professor of Practice, Wong Bing Lai Music and Performing Arts Unit, kimhoip@ln.edu.hk Received 12/12/22 Revised 20/01/23 Accepted 31/01/23

Saath-Saath is “together-together” in the Hindustani language.According to the sleeve notes of the 2-CD album “Re/Semblance: Saath-Saath” (2021) published by PARMA Recordings, the intentional repetition of the word mimics how one might say it in Cantonese or Mandarin.

[2]Introduction to Saath-Saath Project on the official website, http://saathsaathmusic.com

[3]Yangqin (or yang ch’in) 揚琴. Chinese hammered-dulcimer. From around 1600 it was imported to China and became a folk instrument, popular in the coastal regions, Canton, of China.

[4] Omkar’s biographical information is taken from the sleeve notes of the 2-CD album “Re/Semblance: Saath-Saath” (2021) published by PARMA Recordings.

[5]The hotel is called Manjunatha Residency, Jayanagar, Bangalore. The starting time of the interview was 11am local time.

[7] In the chapter on “Taleem- Pedagogy and Performing Subject” of the book Musicophilia in Mumbai (2020) writtenbyTejaswininNiranjana, sheexploredthepedagogicprocessengagedbyIndianvocalists and instrumentalists. She has also quoted Amanda Weidman that notation was seen as a mark of literacy, “and therefore of classical status, and as a transparent and legible representation of orality, and therefore of Indianness.” (p.150)

[8] The concepts of composition and creation in improvisation are not distinguished clearly here. An important aspect of traditional Indian music is its art of improvisation, which is important in traditional Chinese music as well as in many musical traditions of southeast Asia. Professor Chetana Nagajavara discussed this in his book Fervently Mediating. Criticism from a Thai Perspective (2004). In the chapter on the “Arts and Culture of Thailand: A Personal View”, he explains that the improvisational nature shows the faith in the exhaustible power of renewal in artistic creation (p.76), and the concept of “composition” in traditional Thai music does not mean completely new creation (p.79).

[9] The note ‘Ta’ can also be ‘Dha’, pronounced like the word ‘the’ in English.

[10] Kimho Ip, “A Hongkonger in Bangalore - Travelling with Two Bamboo Mallets”. Performance Research: Practices of Interweaving, 25-6/7 (2021): 236.

[11] Kimho Ip, “A Hongkonger in Bangalore - Travelling with Two Bamboo Mallets”. Performance Research: Practices of Interweaving, 25-6/7 (2021): 234.

[12] Due to the pandemic, Omkar was not able to come to Hong Kong again. The recording “Re/Semblance: Saath-Saath” was eventually produced in 2021 with musicians working in recording studios separately in Hong Kong and India.

[13] During the recording, the piece Tore Nagariya in raga Bhairav was played with Indian santoor mallets on my Chinese yangqin.

References

Ip, Kimho. 2021. “A Hongkonger in Bangalore - Travelling with Two Bamboo Mallets”. Performance Research: Practices of Interweaving 25-6/7, 233-239.

Nagajavara, Chetana. 2004. Fervently Mediating. Criticism from a Thai Perspective.Collected Articles 1982-2004. Bangkok: Chomanad Press, 69-87.

Niranjana, Tejaswini. “Saath-Saath: Music Across the Waters”. http://saathsaathmusic.com

Niranjana, Tejaswini. 2020. Musicophilia in Mumbai: Performing Subjects and the Metropolitan Unconscious. Durham: Duke University Press; New Delhi: Tulika Books, 128-161.