PULSE VOL.2 (September 2022)

Abstract

In 1983, the silent movie Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, filmed in Thailand (Siam) in 1925 by Ernest B. Schordsack (1893-1979) and Merian Coldwell Cooper (1893-1973), was presented with a new soundtrack written by Bruce Gaston and the Fongnaam ensemble. Gaston’s music transcended the common format and nature of the movie soundtrack. His work probes the relationship between the past, the present and the future through the fusion of a wide variety of musical styles, including various genres of traditional Thai music, modern Western music, Thai theatrical music and voice, folk music from the jungle, computer generated sound effects and soundscapes, and sounds from newly invented musical instruments crafted by the artist himself.

The pictures on the screen, the live performance of the musicians in front of the screen, and the experience of the audience participating in this theatrical event was a breakthrough in the integration of musical art and science in Thailand. This paper documents and analyzes this important artistic work, with discussion of the premiere performance in 1983, as well as later performances.

Fongnaam performing at PGVIS 2022

The impetus for this paper was a performance that took place on August 22 2022 at the Auditorium of the Princess Kalyani Vadhana Institute of Music in Bangkok, Thailand. On that day, the film Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness was screened accompanied by live music composed by Bruce Gaston. The perfomers, including myself, were members of the Fongnaam ensemble and former students of the late Bruce Gaston. Following the performance there was a short discussion between the anthropologist Yukti Mukdawijit and myself.

“Chang” means an elephant. The film, Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, is a black and white silent film, 68 minutes in length, with occasional English intertitles. The film project was launched in 1925 by American filmmakers Ernest B. Schoedsack (1893-1979) and Merian Coldwell Cooper (1893-1973) with financial and technological support from Paramount. Chang was filmed in Thailand (Siam) during the reign of His Majesty King Vajiravuth Rama VI and was shot over 18 months in several provinces, including Nan, Phrae, Phatthalung, Songkhla, Trang, Suratthani, and Chumphon. The main characters were ethnic Thai farmers, forest hunters, local villagers, and wild animals, including 400 elephants, tigers, leopards,

monkeys, bears, and gibbons. The film premiered in the United States in 1927 at the Riviera Theater in New York. Chang was nominated for Best Picture in the inaugural 1927 Oscar Award. It’s first screening in Thailand was in July 1928. Chang was an international success. The same filmmakers went on to create an even more famous film, King Kong, a romance-tragedy featuring a giant monkey.

Chang begins with a small family in the forest of northern Thailand. Members of the family include Kru (the father), Chantui (the mother), Nah (the son), Ladda (the daughter), a newborn baby, and Bimbo (a domesticated gibbon). As the story opens, the family lives together in peace. The father’s main jobs were farming and cutting trees to build houses. Wild beasts would disturb and devour their pets from time to time, but the father managed to stop them. If the beast were more harmful and beyond the father’s ability to protect his family, he would seek help from the village hunters to help defeat them. One day, the family found that the elephant invasion had damaged their rice fields. They dug a trap to catch the elephants. Eventually however, a baby elephant fell into the pit. The family decided to adopt the baby elephant. The baby’s mother, angered at the loss of her child, came and broke into the house and destroyed everything. The whole family had to flee and ask for help from other villagers. Soon however, hundreds of maddened elephants began flocking to the village. People ran for their lives, and the whole village was completely destroyed. The villagers devised a tactic to take revenge by capturing and taming all the elephants. Eventually, they trained the elephants to work them and peace was restored. The film concludes that humans tend to consider themselves to have abilities superior to other animals, and this can create danger. The film is an examination of the tension between man and nature, and of man’s efforts to control nature.

I will focus on three topics in this paper: 1) the history of live music accompaniments for silent films in Thailand; 2) the mmusical interpretation of Chang by Bruce Gaston and the Fongnaam ensemble; 3) the return of the silent films Chang and new Fongnaam live music in 2022

1) The History of Live Music accompaniments for Silent Films in Thailand

Every on-screen live-action experience allows viewers to use their imaginations. A moving image and a silent narrative text known as “silent films” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries opened up great artistic opportunities for musicians. Improvised music and sound experiments were applied to film screenings to enhance the magic of the cinema from the early days of the artform. Many people have added unique sounds with different voices, sound effects, and carefully crafted compositions to silent films. Later in the 1930s, as technology advanced, light and sound were unified, creating a new standard for modern cinema.

In Thailand in particular, live music performed in front of a screen has been a popular entertainment since the establishment of cinema. Silent films from Europe, America, Japan and other Southeast Asian countries, were shown in Thailand (Siam) since the end of King Rama V’s reign in the early 1900s, and became numerous by the time of King Rama VII’s reign in the 1930s. Live music of the past included Thai mixed string ensembles, called krueng sai psom, or brass bands, called traewong, would play in front of the theatre entrance to persuade people to buy tickets. Once the film started, the musicians would move inside the cinema and play an accompaniment to the story on the screen. Some legendary Thai ensembles, such as the Nai Goon ensemble (mixed string ensembles), Nai Noree ensemble (mixed stringed ensembles), and Nai Ha Chiang Tan band (brass band) accompanied silent films during these early years of cinema. Famous film houses included Wat Tuek Japanese Cinema, Phatthanakon Cinema, Nakon Kasem Cinema, Penang Cinema, Raka Cinema, Chalermkhet Cinema, and Chalermsri Cinema. Later, companies that imported films from abroad, such as Roob Phyont Company, Phatthanakorn Company, and Nakhon Kasem Company, created their own businesses of making musical

accompaniments to films. It was a new and extraordinary business in Thailand for musicians. Prior to the advent of cinema, Thai traditional musicians played only in merit-making rituals, ceremonies, Khon masked dance, Lakhon theatre performances, and traditional festivals. Film provided Thai musicians with both a new artistic outlet and a new source of revenue. The music played by the Thai string ensembles and brass bands were not the specific film scores one would hear elsewhere for the same films. They were songs sung and played for enjoyment, often with a simple and well-known melody. Theatrical “Naphat” songs, such as Cherd, Rua, and Oad were sometimes played to create a conforming atmosphere for the scene. The music could thrill, delight, or sadden Thai audiences, who were familiar with the music from Khon masked dance and Lakhon. Familiar music was used to help make the audience emotionally invested. In addition, brass bands composed special marching songs, with titles such as In front of the Cinema March or Prelude March which sounded similar to Thai popular songs. After World War II, movies with audio came to replace silent films. Consequently, live music performances in front of the cinema and during the shows disappeared.

2) The musical interpretation of Chang by Bruce Gaston and Fongnaam

The music of the early films was different from modern soundtracks. Modern movie soundtracks typically follow the script and are guided by the scene’s mood. Modern soundtracks tend to smoothly fit the cinematic atmosphere and support the dramatic effects of the visual narrative onscreen in a manner that does not distract the audience.

Chang was long forgotten by 1982, when it was rediscovered by Dome Sukwong, a film historian and founder of the Thai Film Archive. Sukwong received a 16 mm film copy of Chang from the U.S. Library of Congress. At that time, he launched a campaign to promote Thai people’s awareness of the importance of old film preservation. Several carefully selected world-class silent films were shown every two weeks at the AUA Language School Bangkok and at the Faculty of Arts at Chulalongkorn University. Sukwong worked with the American pianist- composer Bruce Gaston, who played live piano for several silent films at AUA and Chulalongkorn University. In late 1983, Sukwong invited Gaston to perform piano music for Chang. But when Gaston first witnessed the astonishing scenes of this silent film, he decided that improvised piano performance could not do the film justice. He decided to bring in a Thai music band and to combine it with electronic music to create a more specialized sound. Gaston had studied Thai music in depth with Kru Boonyong Ketkong, and they co-founded the Fongnaam band together in 1982. Gaston’s decision to change the musical performances for this silent film not only created a new opportunity for the Fongnaam band to create a new kind of Thai music, but also allowed him as a composer to create an entirely novel kind of movie soundtrack. Gaston’s instrumentation and use of Thai songs did not follow the old traditions of silent film music.

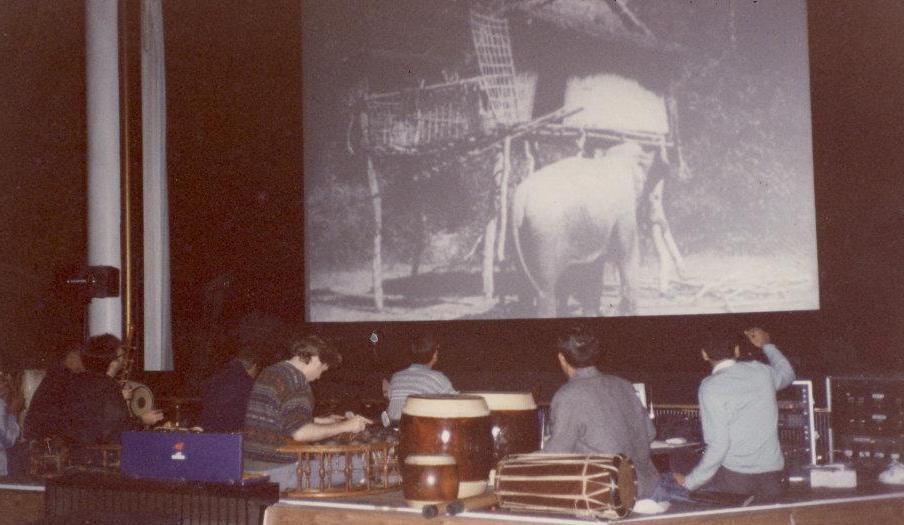

Fongnaam at AUA in 1983

Fongnaam’s first performance of live music for Chang was given at the AUA Auditorium on November 22, 1983. The musicians were early Fongnaam members Boonyong Ketkhong (gong circle), Boonyang Ketkhong (bass xylophone), Chamnian Srithaipan (flute), Bruce Gaston (leading xylophone & electronics keyboard), Annop Jansuta (Drums), and Jiraphan Angsavanon (electric guitar). The instrumentation were piphat instruments associated with Thai royal court and ceremonial music, and folk instruments from the north of Thailand, including the sueng (long-neck lute) and salor (coconut fiddle). Several small percussion instruments were also used in this first performance to create color during the forest music scene. The most prominent repertoire was the ancient suite, Phleng Ching Chang Prasan Nga (“Elephants gather their tusks together”), which was used as the main theme of the show. There were several traditional theatrical songs played by Boonyong Kethkong with keyboard improvisation by Bruce Gaston. According to Sukwong, the performance at the AUA was successful. A full house of both Thai and foreigners came to the event. The musicians and the audience both faced the screen. They watched movie together while the spinning film rolled forward.

A second live performance took place in 1990 at the National Theater and the National Museum, Bangkok at a charity event titled Chang Chuay Piano (“Elephant helps the damaged Piano”) curated by the Cultural Affairs Association along with the Thai Film Archive and the Dinsorsee group. The main purpose of this event was to raise funds for the conservation and repair of the antique Piano that once belonged to the Siamese prince. This performance was presented by the 2nd generation of Fongnaam members, including Boonyong Ketkong (bass xylophone), Bruce Gaston (electronic keyboard & drums & pi jum), Lamoon Phuakthongkham (leading xylophone & “manni xylophone”), Phin Ruangnont (Taphon drum & bamboo tubes), Prasarn Wongwirotrak (gong circle & sung & salor), Kaiwan Tilogavichai (computer). The band instruments included the Central Piphat instruments, Northern Lanna instruments, bamboo musical instruments from the Manni ethnic group of southern Thailand, and a synthesizer. A new overture, Aiyaret, composed by Boonyong for the Piphat ensemble, was performed prior to the film. A special program booklet titled “Chang Music Festival” was also produced. In late 1990, the American film company Milestone was legally authorized by the US government to manage the public rights of Chang. Milestone has restored the film, changing it from 16mm to 35mm film. The company also officially commissioned Bruce Gaston to compose the film’s soundtrack.

Bruce Gaston spent a lot of time studying the film in detail. He analyzed every aspect of the visual content and the subtle elements in the performances of actors and behavior of the animals.[2] He redesigned the sounds of nature using his computer programs and experimented with various combinations of different musical styles. He also relied heavily on advice from Boonyong Ketkong. The long-term experiences and memories of both teacher-students have been preserved in many of the songs that appeared in this new work. These new songs include a complete version of Phleng Ching Changprasarn Nga, Krow Khaek Ngor thao, Fongnaam chandio, and Boonyong’s rearrangement of Naphat’s song Krow Nok.

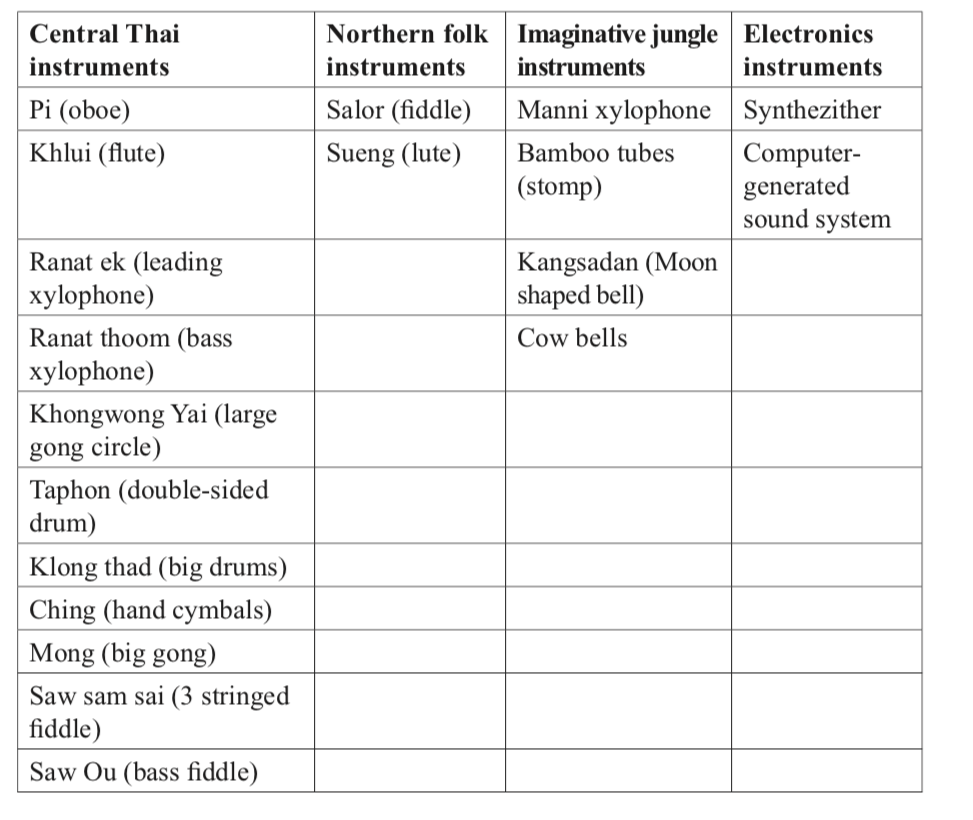

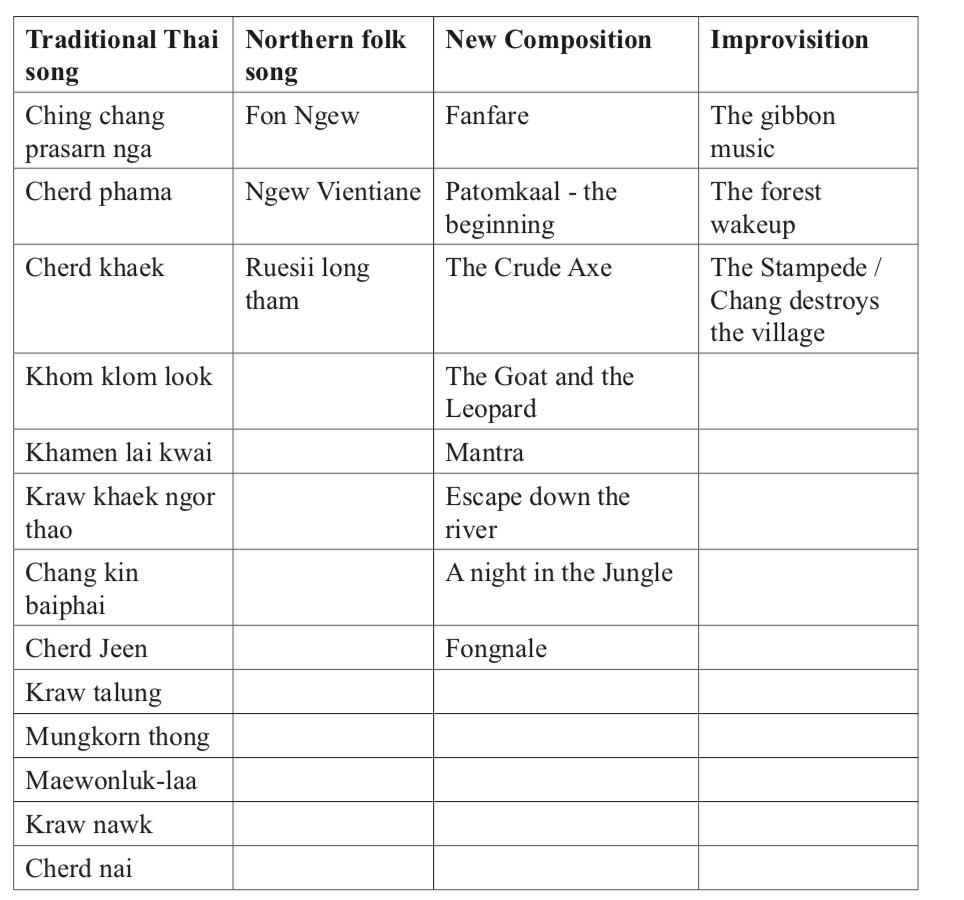

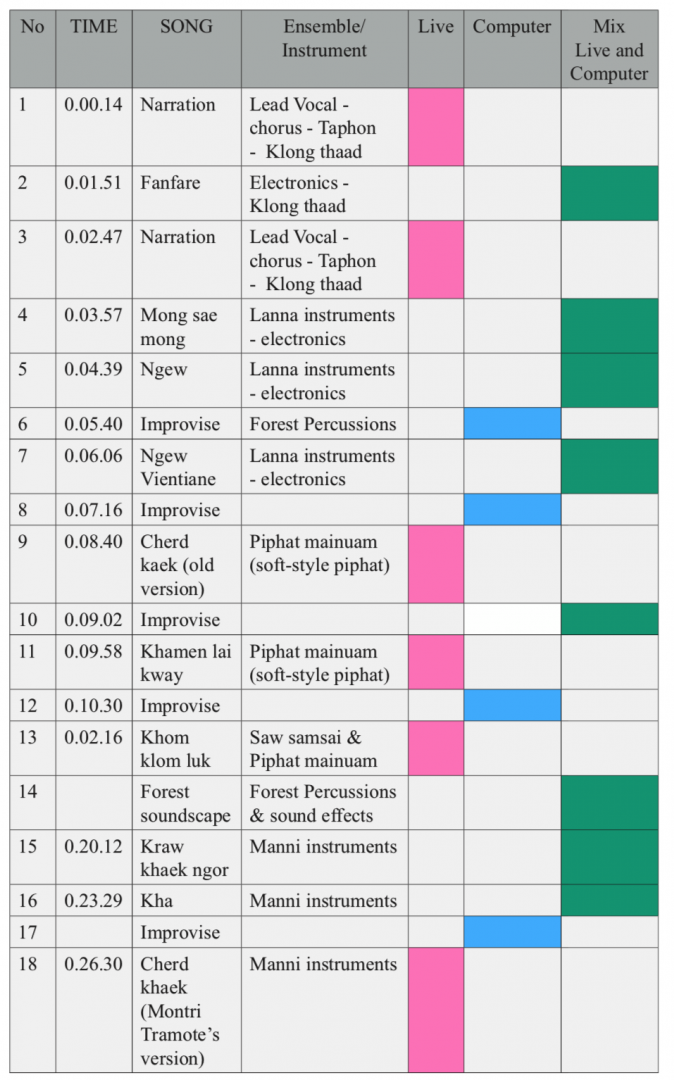

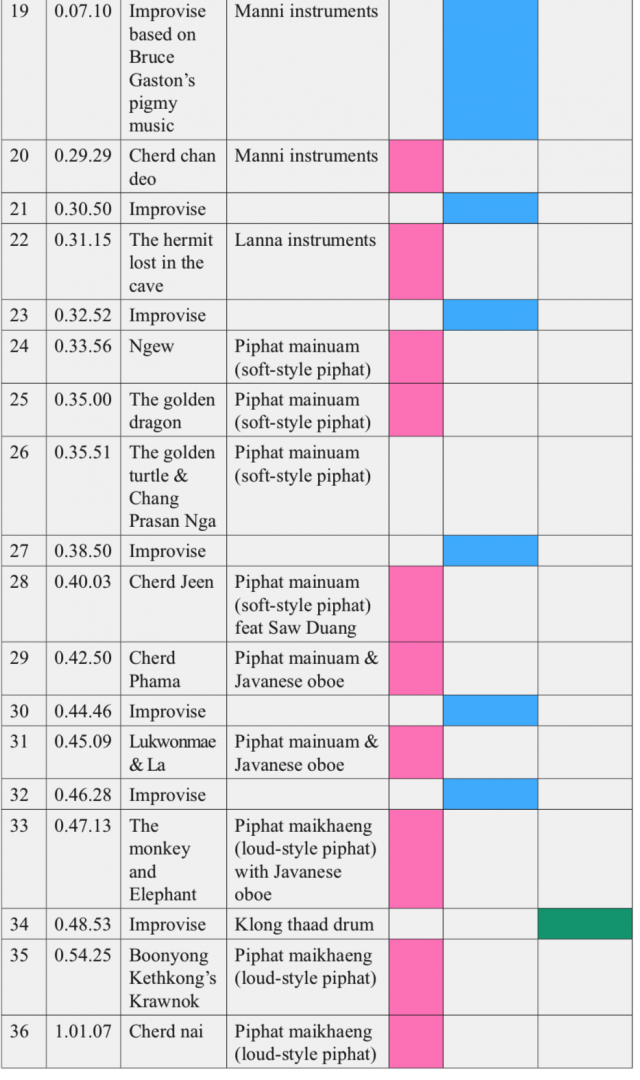

Bruce Gaston eventually brought the Fongnaam band to the center stage recording studio to record the soundtrack. Guest artists such as Suwit Kaewkamol (oboe & flute), Lerkiat Mahavinichaimontree (saw sam sai three stringed fiddle), Sombat Sangvienthong (narrator), Solot Kooptaratana (bamboo) joined the event. It took almost three months to complete the entire job. Various elements were added during the recording process, such as the narration of Nang Yai’s tradition, the electric fanfar prelude, the new Lanna song, the Munni ethnic voices, and the orchestration of natural sounds. Bruce Gaston and Milestone’s work was eventually sold in cassettes, CD and in videotape. Table 1 below shows the instruments used in the soundtrack, grouped according to type. Table 2 shows the various songs heard on the soundtrack, grouped according to type.

Table 1. Instruments heard on the Chang soundtrack, recorded in 1990.

Table 2. Songs on the Chang soundtrack, recorded in 1990.

Gaston and the Fongnaam ensemble did not work from written scores. All musicians worked using the oral tradition, learning and memorising their parts by heart. The soundtrack includes several improvisations as well.

Fongnaam in the UK in 1991

In June 1991, the Fongnaam ensemble traveled to the United Kingdom. They spent almost a month performing and recording in several cities, including London, York, Suffolk, Birmingham, Liverpool and Bournemouth. One of their most important activities was performing live along with the new 35 mm restored version of the Chang film. Fongnaam members in the UK chapter include Boonyong Ketkong (bass xylophone), Bruce Gaston (electronic keyboard & drums & pi jum), Lamoon Phuekthongkham (leading xylophone & “manni xylophone”), Suwit Kaewkramon (oboe&flute), Phin Rueangnon (drum & bamboo), Somchan Boonkerd (drum & percussions), Prasan Wongwirotrak (Gong circle & sueng), Kaiwan Kulwattanothai (computer), and myself (percussions). During this trip, Fongnaam shared experiences from the past in Thailand, especially in relation to differences between Thai and British/European audiences’ perspectives. The band also explored new methods for controlling synthetic sounds through Apple computer technology. This trip was the last time that Bruce Gaston, Boonyong Kethkong and the band members worked together on live music for the film.

3) The return of the silent films Chang with new live music in 2022

Fongnaam team at Lido in Bangkok 2022

Over the next three decades, several former Fongnaam members, including Boonyong Ketkhong, Bruce’s mentor, passed away. In late 2021, Bruce Gaston himself passed away. Shortly after his death, Maren Niemeyer, the director of the Goethe Institute Bangkok, hosted the Open-Air Kino Festival. She invited the Fongnaam bandunder the new leadership of Theodore Gaston to perform special live music for Chang in remembrance of Bruce Gaston’s contributions to contemporary Thai society. The Goethe-Institut contacted the Milestone company for a screening license and asked for a new digital film copy in high resolution. Apart from the old members of Fongnaam, which consisted of myself, Kaiwan Kulwattanothai, and Prasarn Wongwirojrak, the following new members performed as well: Lerkiat Mahavinitchaimontree, Somnuek Sang-run, Tossaporn Tassana, and Kriangkrai Wareewat. The performance took place on February 1, 2022. This performance was as spontaneous and alive as those that were given when Bruce Gaston was alive.

Reviving the live music to accompany Chang was exciting for all of those involved. Due to the length of time that had passed since the last performance, we had to revisit the scenes’ details and trace the songs that Bruce Gaston had written and arranged. Modern computers couldn’t read the old diskettes, so we had to find another way to get to know our parts. The original music software also no longer functioned. Therefore we had to find modern software and sound technologies to replicating the original soundtrack and sound design. We eventually managed to recreate the sequence of live songs and pre-recorded sounds based on the movie’s timecode. Table 3 shows the music cues for the performance. Notated musical examples can be found in the appendix.

Table 3. Music cues for the 2022 live performance of the silent film Chang with music by Bruce Gaston.

My most thrilling memory is of returning all the Thai instruments back to their original tuning frequencies, as heard on Bruce Gaston and Boonyong Kethkong original recordings from thirty years ago. This was necessary since the current tuning system of Thai instruments and electronic instruments has changed dramatically over the years. This is especially true of Thai instruments, which are now tuned according to the Western system.

Nowadays, the young generation uses computer applications and the internet to make rehearsals and concert management run smoothly. New and old were brought together in this project: digital monitors with guidelines and timecodes were combine with the original Fongnaam musicians’ special memories to bring Chang to life once again.

From May 6 to 8 2022, FAAMAI Digital Arts Hub at Chulalongkorn University, in cooperation with the Ministry of Culture and the Goethe Institute, hosted a live music performance of Chang by Fongnaam. The screening and performance took place at the Lido Cinema in Bangkok. Thailand. In addition to the screening and performance, the event featured exhibitions, bilingual program notes, and a bilingual discussion by people who knew Bruce Gaston and the film. This performance was designed to uncover and disseminate knowledge of the techniques used by Gaston to combine Thai music and computer-controlled electronic sounds for the specific purpose of accompanying a silent film.

The latest performance took place on August 22, 2022, at the Princess Galyani Vadhana International Symposium (PGVIS). The silent film and live music once again brought to life a work of art that connects past, present and future. Staff at

the Princess Galyani Vadhana Instite of Music added video mapping to enhance the beauty of the film.

To me, anytime silent film and live music appear together, it signifies our special waikruu: a commemoration and a celebration of the beautiful spirit of Bruce Gaston, a teacher, a composer, and innovative genius; an artist that embodies the spirit of both traditional and contemporary Thai music.

Fig 7. Bruce Gaston

As a coda of to this paper, I quote the remarks of the Australian ethnomusicologist John Garzoli, whose thoughtful words express well Bruce Gaston’s monumental achievement with this work:

The value of creating a musical accompaniment to the movie “Chang” is to voice the sound of people in the culture where humans coexist with animals and the transition of such culture and environment. The music created by Bruce Gaston and Fong Naam reflects Gaston’s desire to faithfully honor the beauty and dignity of the musical past while staring directly into the eyes of the future and grabbing it with both hands. The sounds represent a monumental leap into an unknown new world that continue to raise questions about Thailand’s eternal struggle with the excesses and shallowness of modernity.

Although the screenplay was created by foreigners who traveled across the sea to capture Siamese culture 95 years ago, the trim is an important piece of evidence in the history of filmmaking in Thailand since it reveals the ways of thinking that influenced the way films were made. A number of questions in relation to Bruce Gaston’s approach to the trim and the sounds he created from pictures on the screen await consideration, if not outright answers. His revolutionary approach to rearranging musical tunings and pitch within his overall sound design stands out as a significant musical and cultural question. It is also worth considering the changeable nature of his multiple perspectives as he was simultaneously cast as a performer, composer, and audience member with special license to shape the performance through his direct creative interventions. ( Garzoli, 2022 p.25)

[1] Notable composers in the silent film era include John Stepan Zamecnik (1872 – 1953),

Richard E. Hildreth (1867-1943), and Maurice Baron (1889-1964).

See Martin Miller Marks (1997). Music and the Silent Film: Contexts and Case Studies, 1895– 1924. New York: Oxford University Press. See also Gillian B Anderson (1988). Music for silentfilms,1894-1929. LibraryofCongress,Washington,monographic,1988.Pdf.https://www. loc.gov/item/87026248/.

[2] The description of Gaston’s working process presented in this paper is based on my personal

experience of working with him from 1989 until his death 2021.

References

- FAA MAI (2002). Program book Silent film “Chang”@Lido Connect

- Milestone. (1995). Chang a drama of the wilderness press kit.

- Sukhawong, Dome. (1990). The Knowledge Dissemination Book of the CulturalActivities Association Vol.4: The Music Entertainment “Chang” by the Fong

Naam Orchestra. Bangkok: The Cultural Activities Association

- Kobel, Peter (2007). Silent Movies: The Birth of Film and the Triumph of Movie Culture (1st ed.). New York: Little, Brown and Company.

- Marks, Martin Miller (1997). Music and the Silent Film: Contexts and Case Studies, 1895–1924. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Anderson, Gillian B (1988). Music for silent films, 1894-1929 a guide. Library of Congress, Washington.https://milestonefilms.com/products/chang